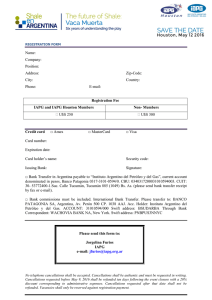

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340463291 Paleopathological Research in Southern Patagonia: An Approach to Understanding Stress and Disease in Hunter-Gatherer Populations Article in Latin American Antiquity · April 2020 DOI: 10.1017/laq.2020.5 CITATIONS READS 0 205 1 author: Jorge Suby National University of the Center of the Buenos Aires Province 70 PUBLICATIONS 430 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Archaeology of the fuegian steppe. Analyzing hunting sites. View project All content following this page was uploaded by Jorge Suby on 20 May 2020. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. ARTICLE Paleopathological Research in Southern Patagonia: An Approach to Understanding Stress and Disease in Hunter-Gatherer Populations Jorge A. Suby This article reviews the most relevant data regarding evidence of stress and disease in native populations from Southern Patagonia and proposes future directions for paleopathological research. It focuses on the disease patterns in hunter-gatherer societies and the changes produced by contact and colonization. Studies of oral pathologies show a high frequency of dental attrition and low frequency of caries and antemortem tooth loss. Individuals with terrestrial dietary patterns show evidence of higher mechanical stress in the spine than those who participated in marine economies, based on the prevalence of Schmorl’s nodes and vertebral osteophytosis. Porotic hyperostosis is more prevalent in individuals who had a marine diet and is probably related to nutritional impairment and parasitic infections. A higher frequency of metabolic stress was identified in individuals who lived in missions, perhaps because of declining quality in diet, hygiene, and living conditions. Paleoparasitological studies identified several species of parasites associated with human skeletons and terrestrial fauna. Moreover, recent studies suggested that treponematosis and tuberculosis were present in Patagonia since at least 1000 years BP. Future paleopathological research should increase the size and quality of studied samples and apply new methods and interpretive criteria. Detailed research into infections, degenerative joint diseases, and trauma (including violence episodes) has rarely been conducted. Keywords: skeletal disease, paleopathology, Southern Patagonia, review El objetivo de este trabajo es revisar y discutir los conocimientos más relevantes logrados hasta el momento acerca de las evidencias de estrés y las enfermedades de las poblaciones cazadoras-recolectoras de Patagonia Austral. Se proponen, además, perspectivas futuras para las investigaciones paleopatológicas en la región que permitan discutir los patrones de las enfermedades, su asociación a los estilos de vida y los cambios producidos por el contacto y la colonización. Los estudios sobre patologías orales muestran altos grados de atrición dental y bajas prevalencias de caries y pérdida dental antemortem. Se detectó mayor estrés mecánico en la columna vertebral en sociedades con economías terrestres que en aquellas con economías marítimas. Por el contrario, se hallaron mayores prevalencias de hiperostosis porótica en individuos asociados a dietas marítimas, atribuida probablemente a trastornos nutricionales e infecciones parasitarias. Los estudios parasitológicos muestran abundantes reportes de especies terrestres en restos humanos y faunísticos. Estudios recientes detectaron posibles casos de tuberculosis y treponematosis. A pesar de estos avances, las futuras investigaciones deberán estar orientadas a aumentar el número y calidad de las muestras analizadas. En especial se requieren análisis de mayor alcance sobre lesiones patológicas articulares, infecciosas y traumáticas, escasamente estudiadas hasta el momento. Palabras clave: lesiones en restos esqueletales, paleopatología, Patagonia Austral, revisión S ince at least the mid-1980s, bioarchaeologists worldwide have discussed the evidence of stress and disease patterns in ancient hunter-gatherers. This research has mainly focused on (1) the changes produced by the adoption of agriculture and (2) the impact of contact and colonization in the Americas and other regions of the world. It has recognized stress and disease as complex phenomena, derived from wider interpretations of the association between human health and subsistence strategies, migration processes, demography, and ecological interaction with other species, all of which are affected by cultural and biological contexts (Cohen 2009; Roberts 2016). In this biocultural and evolutionary framework, the knowledge of Jorge A. Suby ▪ INCUAPA-CONICET, Bioarchaeological Research Group. Department of Archaeology, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of the Center of Buenos Aires Province, Argentina. 508 Street No. 881, Quequén (7631), Buenos Aires, Argentina ( jasuby@conicet.gov.ar) Latin American Antiquity, pp. 1–17 Copyright © 2020 by the Society for American Archaeology doi:10.1017/laq.2020.5 1 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 181.31.179.8, on 06 Apr 2020 at 15:27:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5 2 LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY stress and disease in past societies constitutes a necessary step to understanding human evolution. Concerning the replacement of the huntinggathering lifestyle, researchers commonly argue for a decline in health, evidenced by less varied diet, reduced stature, more frequent malnutrition, and increasing frequencies of infectious and oral diseases (Cohen 2009; Cohen and Armelagos 1984; Cohen and Crane-Kramer 2007; Pinhasi and Stock 2011; Roberts 2015). Nevertheless, some hunter-gatherer groups have shown more prevalent stress and a greater frequency of disease than agriculturalist societies (e.g., Cohen and Crane-Kramer 2007; Domett and Tayles 2007; Jackes et al. 1997; Toomay Douglas and Pietrusewsky 2007). In a similar way, it was commonly assumed that the health of hunter-gatherer populations was probably better before the arrival of Europeans to the Americas than after colonization. Nevertheless, paleopathological and bioarchaeological research produced since the 1990s has shown a much more complex biocultural phenomenon (Murphy and Klaus 2017), based on temporal and spatial variability in disease patterns from pre- to postcontact times not only in America (e.g., Klaus and Alvarez-Calderón 2017; Larsen 2001; Larsen and Milner 1994; Stojanowski 2013; Verano and Ubelaker 1992) but also in other regions, including South Africa (Ribot et al. 2017) and Australia (Webb 1995). Therefore, stress and disease patterns in hunter-gatherers were probably not universal (Cohen 2009), and new data are necessary to understand the possible variability related to their economic strategies, their cultural lifestyles, and the changes produced by both the adoption of agriculture and contact with European colonizers. Southern South America is one of the few places around the world that was inhabited by numerous hunter-gatherer populations in a wide range of cultural and ecological contexts at the moment of Native–European contact and later. For that reason, information regarding stress and disease in these populations and the association of these conditions with different ecological and cultural contexts could offer valuable insights for the interpretation of other hunter-gatherers worldwide. Indeed, a great amount of paleopathological data in skeletal remains of hunter-gatherer populations from Argentina has been produced in the last two decades (see Luna and Suby 2014 for a review). Within this body of research, the study of ancient marine and terrestrial hunter-gatherer populations who lived during the Holocene in Southern Patagonia (Figure 1), the continental and insular territory below latitude 50°S, has increasingly received attention. Most of the studies produced during the 1990s focused on oral disease, degenerative joint disease, and some stress markers such as cribra orbitalia, porotic hyperostosis, and lineal hypoplasia of the dental enamel (e.g., Aspillaga and Ocampo 1996; Aspillaga et al. 1999; Constantinescu 1997, 1999). These results were frequently descriptive and were assumed to be indicators of adaptation of human societies to the cold and harsh environment in which they lived; only a few authors offered quantitative data of disease patterns from skeletal samples (e.g., Castro and Aspillaga 1991; Guichón 1994; Pérez-Pérez and Lalueza-Fox 1992). In contrast, during the two first decades of the twentyfirst century, researchers focused on the study of the spatial and temporal distribution of bone and oral diseases and skeletal lesions, the association of these phenomena with economic and dietary patterns, and the possible health changes produced as a consequence of Native–European contact. Most of these studies were based on quantitative data interpreted through paleopathological and bioarchaeological approaches (e.g., AlfonsoDurruty et al. 2011; García Guraieb 2006; Guichón et al. 2015; L’Heureux and Amorosi 2009, 2010; Sáez 2008; Santiago et al. 2011; Schinder and Guichón 2003; Suby 2014a, 2014b; Suby et al. 2009; Zúñiga Thayer et al. 2018). Despite the large amount of paleopathological data produced during that time, no integrative analysis of the available information from skeletal remains of hunter-gatherers from Southern Patagonia has been presented to date. Consequently, the aim of this article is to review the most relevant paleopathological results reported during the last two decades from these populations, which may be useful in understanding the stress and disease patterns related to hunter-gatherer lifestyles. Taking into account the current knowledge, I then propose future directions for research. Moreover, I present the ethnographic and archaeological information Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 181.31.179.8, on 06 Apr 2020 at 15:27:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5 Castro et al. 2008 1740 ± 60 Carsa 1 Treponematosis M Young adult F ND F F M 728 ± 39 BP Contact period ND ND 1151 ± 59 Salitroso Lake (skeleton SAC 4-1-1) Puqueldón 1 Meulin 3 Castro 5 Yanquenao 55–59 Adult 26 ± 2 27 ± 1 40–50 Costillas M-F Adult Vertebra Vertebra Skull, tibias, clavicle, Skull Frontal and nasal bone, tibias, fibulas, radios and ulnas Skull, ribs, pelvis and long bones Morphologic García Laborde et al. 2010; García Laborde 2017 García Guraieb 2006 Sáez 2008 Rodríguez Balboa et al. 2014 Rodríguez Balboa et al. 2014 García Guraieb et al. 2009 MorphologicDNA Morphologic Morphologic Morphologic Morphologic Morphologic Vertebra Vertebra 18–23 25–30 Type of analyses Bone lesion Age (years) Sex Chronology Archaeological site Infectious disease Infectious diseases in skeletons from Southern Patagonia have been little researched. Most case studies are of tuberculosis, osteomyelitis, and periosteal reactions, the latter of which are usually interpreted to be bone infections, despite the fact that other metabolic, traumatic, and vascular diseases could be involved (e.g., Roberts 2019; Weston 2012). Moreover, many paleoparasitological results were published during the last decade. The most relevant results are briefly described in this section. Tuberculosis and Treponematosis. The study of tuberculosis (TB) in past populations from South America gained importance in the last decade. Nine skeletons recovered from five archaeological sites in Patagonia were suggested to be potentially affected by TB (Table 1; Figure 1). García Guraieb (2006) presented a morphological description of vertebral lesions attributed to TB in the skeleton SAC 4-1-1, a female adult individual dated to 728 ± 39 years BP (Goñi et al. 2003–2005) from Salitroso Lake, a mortuary area of about 200 km2 in the northwest Santa Cruz province (Argentina) with numerous burials dated from about 2600 to 350 BP (García Guraieb et al. 2015). In this study, bone lesions were presented as compatible with suffering from Pott’s disease. Molecular analyses, which could help support the diagnosis of TB in this skeleton, were not reported. More recently, Guichón and colleagues (2015) analyzed a possible case of TB in a skeleton from the precontact site of Myren 1 (n = 1; 640 ± 20 years BP, Northern Tierra del Fuego, Chile), which was previously diagnosed as TB by Constantinescu (1999). Nevertheless, molecular and new osteological data did not conclusively demonstrate that TB was the origin of the vertebral hypervascularization identified in this skeleton (Guichón et al. 2015). From a postcontact archaeological context, Castro and Aspillaga (1991) reported on a Halakwalup skeleton (skeleton 417, housed at the National Museum of Natural History in Table 1. Skeletal Remains Suspected to Be Possible Cases of TB and Treponematosis in Southern Patagonia. Infectious Diseases M M Recent Paleopathological Researches 3 Myren 1 ca. 640 ± 20 Skeleton 417 – National Museum of Contact period (Dawson Natural History, Santiago (Chile) Island Salesian Mission) Salesian Mission of Rio Grande (n = 5) ca. 100 BP Reference about the lifestyle of these hunter-gather populations that is most relevant to the interpretation of paleopathological results (Supplemental Text 1). Morphologic-DNA Guichón et al. 2015 Morphologic Castro y Aspillaga 1991 PALEOPATHOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN SOUTHERN PATAGONIA Tuberculosis [Suby] Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 181.31.179.8, on 06 Apr 2020 at 15:27:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5 4 LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY Figure 1. Location of archaeological sites in which skeletons diagnosed with TB and treponematosis were recovered. Santiago, Chile), recovered from the cemetery of the Dawson Island Salesian Mission (Chile), with osteolytic lesions in the L5–S1 vertebrae and in one of the tibias, diagnosed as TB and osteomyelitis. The authors offered no detailed description, and no other analyses have been conducted on this skeleton. In Tierra del Fuego, García Laborde and colleagues (2010) and García Laborde (2017) reported the presence of periosteal reactions in the vertebral end of the ribs in 5 of the 33 skeletons recovered in the cemetery of the Salesian Mission “La Candelaria” (Rio Grande, Argentina), which were attributed to TB or other pulmonary infectious disease. Studies of historical sources (Casali et al. 2006) showed a high mortality from pulmonary diseases, including TB, among native individuals who lived in that mission. Although the authors recognized problems in the diagnosis of TB during the nineteenth century (García Laborde 2017), historical data could support that diagnosis in these skeletons. Finally, Sáez (2008) described lytic lesions in a vertebra, a sacrum, and a sternum in the Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 181.31.179.8, on 06 Apr 2020 at 15:27:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5 [Suby] PALEOPATHOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN SOUTHERN PATAGONIA postcontact commingled skeletal remains from Puqueldón 1 site (Región de los Lagos, Chile), which the author suggested were caused by TB. Treponematosis was also suggested in four cases from Patagonia (Figure 1), although from a region farther north than I discuss here. Castro and others (2008) described bone lesions in a male young adult skeleton from the site of Carsa 1 (Santa Cruz, Argentina), dated to 1740 ± 60 BP (Moreno et al. 2011). The skull, ribs, pelvis, and long bones were affected by osteolytic lesions. García Guraieb and colleagues (2009) reported a possible case of treponematosis in a 40- to 50-year-old male from the Cerro Yanquenao site (Chubut, Argentina), dated to 1151 ± 59 BP, with active osteolytic lesions in the frontal and nasal bones and in the long bones including the tibias, fibulas, radiuses, and ulnas. Finally, Rodríguez Balboa and colleagues (2014) presented lesions compatible with treponematosis in two uncontextualized skeletons recovered in the Meulin 3 and Castro 5 archaeological sites, in the big island of Chiloé (Chile). The first case presented saber tibiae and caries sicca, whereas the second one is an isolated skull with caries sicca-like lesions (Table 1). Periosteal Reactions and Osteomyelitis. Although periosteal reactions have been reported on many occasions (e.g., Constantinescu 1999; Guichón and Suby 2011; L’Heureux et al. 2003; Santiago et al. 2011), only two studies are specifically centered on this condition, both of which regarding skulls. Guichón (1994) studied 54 skulls and mandibles from Tierra del Fuego and southern continental Patagonia, most of them undated. In this sample, 12.9% of individuals exhibited periosteal reactions in their crania. Unfortunately, no details about the localization, extension, or degree of the lesions were mentioned in that research. More recently, Ponce and colleagues (2008) presented a study of external auditory exostosis in 108 skulls from Tierra del Fuego without including details about the studied sample or the possible association of these traits with diving in cold water. The results showed a prevalence of 9.1% in individuals associated with marine economies, in contrast to a prevalence in individuals with terrestrial habits of 1.9%. However, Pandiani and others (2018) studied external auditory exostosis in a sample of 24 pre- and postcontact skulls 5 from Southern Patagonia following the method suggested by Standen and colleagues (1997). The results showed that 79.2% of studied individuals were affected by auditory exostosis of a small size in most of the individuals (63.2%); this condition was not related to economic strategies or chronology. Regarding osteomyelitis, a recent analysis published by Suby (2014c) showed that 10 of 25 adult skeletons from Southern Patagonia presented slight striated new bone formation on long bones, mainly in the tibias, without any other lesions presumably caused by unspecific infections. Only two cases (8%) could be assumed to be produced by osteomyelitis, as indicated by the presence of woven and sclerotic new bone formation and cloacae. In one case it affected a left tibia of the skeleton recovered in the Shamakush entierro 6 site from Southern Tierra del Fuego, dated to 1536 ± 46 years BP (Suby et al. 2011). The other case was present in a right tibia of the undated skeleton recovered from the site of Palermo Aike, Santa Cruz, Argentina, probably related to a distal bone fracture (Figure 2). Paleoparasitological Analyses. Numerous paleoparasitological studies have been conducted on sediments associated with human skeletons, the remains of clothes, and human and nonhuman coprolites. The most commonly identified specimens were eggs of Ascaris Figure 2. Cases of osteomyelitis suggested in skeletal remains from Southern Patagonia. Top: Left tibia of the skeleton recovered in Shamakush burial No. 6 (Southern Tierra del Fuego), with a possible cloaca on the diaphysis. Bottom: right tibia of the skeleton recovered in the archaeological site Palermo Aike (southern continental Patagonia), in which a displaced remodeled fracture and a cloaca were identified (Color online). Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 181.31.179.8, on 06 Apr 2020 at 15:27:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5 6 LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY lumbricoides and Trichuris trichiura (e.g., Fugassa 2015; Fugassa et al. 2008), parasites probably related to the ecological interaction of humans with terrestrial vectors (Araújo et al. 2011). According to Fugassa (2006), these parasites are particularly abundant in remains from the postcontact period. Many species were further identified in animal coprolites, especially canids, rodents, and camelids. Capillaria sp., Uncinaria sp., Toxascaris sp., Physaloptera sp., and Moniezia sp. were reported, although it is not clear if they would affect human health (Fugassa et al. 2006; Taglioretti et al. 2017). Ectoparasites like Demodex sp. were also recorded in remains of Selk’nam clothes made using guanaco furs (Fugassa et al. 2007; Taglioretti et al. 2017). Oral Diseases Studies of oral pathologies included analyses of caries, antemortem and postmortem tooth loss, dental attrition, and periapical lesions. The methods of analysis were not clearly described by some authors, and others used different criteria for the same studies. For that reason, full comparison between results is challenging and will probably require new insights. The main results pertaining to caries are summarized in Table 2. Most of the studied skeletons have not been dated, and for that reason, temporal changes cannot be described. For the most part, authors found a low prevalence of skeletons with caries, with the exception of Guichón (1994). Pérez-Pérez and Lalueza Fox (1992) studied 165 crania housed in museums from Chile and Argentina, ethnographically classified as Aonikenk, Selk’nam, Kaweshkar, and Yámana (Supplemental Text 1), reporting only 7.3% of the individuals as having caries. In contrast, Guichón (1994) analyzed 60 crania, mostly from numerous archaeological sites in Tierra del Fuego that lacked chronological data: 40% showed at least one caries and 11% between three and six caries. The same study reported higher frequency of caries in individuals from Northern Tierra del Fuego and the Última Esperanza region in continental Chile than in Southern Tierra del Fuego. Later, Schinder and Guichón (2003) studied the presence of caries in a small sample of 20 crania, principally from Northern Tierra del Fuego, and the relationship between this dental pathology and diet, which was identified through stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen. The results showed higher frequency of caries in individuals with maritime diets (33%) than in those with terrestrial (25%) or mixed diets (25%). More recently, L’Heureux and Amorosi (2009) and Suby and colleagues in Santa Cruz (2009) and in Southern Tierra del Fuego (Suby et al. 2011), as well as Santiago and colleagues (2011) in the Atlantic coast of Tierra del Fuego, did not find individuals with caries (Table 2). Among skeletons from the postcontact period, Castro and Aspillaga (1991) studied 30 skulls from the cemetery of the mission on Isla Dawson. Only the Kaweshkar’ skeletons showed caries, with a frequency of 17% in adults and 14% in subadults. In a similar historical context, García Laborde and colleagues (2010) analyzed human remains from the Salesian Mission of Rio Grande. Sixty-seven percent of the studied individuals exhibited at least one caries. These results suggest a higher frequency of caries in the postcontact period than observed in skeletal collections without chronological references or from the precontact period. A low frequency of antemortem tooth loss (AMTL) has been typically reported, with some exceptions and differences among groups. Pérez-Pérez and Lalueza Fox (1992) reported a higher prevalence in Selk’nam (2.6%) and Aonikenk (5.7%) than in Kaweshkar (0.2%) and Yamanas (1.7%), whereas Guichón (1994) identified a prevalence of 17.9% in the complete analyzed sample. Moreover, Schinder and Guichón (2003) showed a higher prevalence in individuals with terrestrial (33%) and mixed (20%) diets than in those with marine (2%) diets. L’Heureux and Amorosi (2009) described 43% of the individuals in a sample of nine from the site Cañadón Leona 5 as exhibiting AMTL. In a sample from the postcontact period, García Laborde and others (2010) observed 33.3% of the individuals as exhibiting AMTL. Most results relating to dental attrition are consistent, showing high attritional wear. Guichón (1994) studied a sample of 639 teeth from 52 individuals following the categories proposed by Molnar (1971). Their results show that 54% Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 181.31.179.8, on 06 Apr 2020 at 15:27:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5 [Suby] PALEOPATHOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN SOUTHERN PATAGONIA 7 Table 2. Frequency of Caries Recorded in Skeletal Human Samples from Southern Patagonia. Caries Authors Period L’Heureux and Amorosi 2009 Perez-Perez y Lalueza Fox 1992 Precontact Unknown Guichón 1994 Unknown Schinder and Guichón 2003 Unknown Castro and Aspillaga 1991 Postcontact García Laborde et al. 2010 Postcontact Santiago et al. 2011 Suby et al. 2011 Suby et al. 2009 Pre- and postcontact Pre- and postcontact Pre- and postcontact of teeth correspond to categories 5, 6, and 7, with canines and incisors the most affected by attrition. Moreover, Pérez-Pérez and Lalueza Fox (1992) reported a higher rate of dental attrition in Aonikenk individuals, especially in posterior dentition. In the same way, L’Heureux and Amorosi (2009, 2010) found a high degree of dental wear, in this case following the Scott (1979) and Smith (1984) methods. Other analyses (e.g., Kozameh and Benitez 2005) show similar results in individuals from the southeastern extreme of Tierra del Fuego. Pérez-Pérez and Lalueza Fox (1992) also studied the presence of dental abscesses, reporting a lower frequency in Kaweshkar than in other groups from Tierra del Fuego. Schinder and Guichón (2003) reported that 25% of the skeletons associated with terrestrial and mixed diets were affected by abscesses, whereas each of the three analyzed individuals with a marine diet showed this trait. In contrast, Castro and Aspillaga (1991) found a higher prevalence of Sample Cañadón Leona site (n = 9) Total (n = 165) Selk’nam (n = 60) Aonikenk (n = 16) Kaweshkar (n = 20) Yamana (n = 28) Total (n = 60) Big Island of Tierra del Fuego (n = 30) San Gregorio (n = 14) Beagle Channel (n = 13) Última Esperanza-Magallanes (n = 3) Total (n = 19) Terrestrial diet (n = 8) Mixed dieta (n = 8) Maritime diet (n = 3) Total (n = 38) Kaweshkar (n = 30) Selk’nam (n = 6) Yamana (n = 2) Salesian Mission of Rio Grande (n = 9) Atlantic coast of Tierra del Fuego (n = 11) Coast of Beagle Channel (n = 12) Meridional Coast of Santa Cruz (n = 8) % Individuals with caries 0.0 7.3 11.7 0.0 15.0 3.6 40.0 50.0 23.3 21.7 5.0 26.0 33.0 25.0 25.0 16.0 17 (adults), 14 (nonadults) 0.0 50.0 67.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 abscesses in Selk’nam (57%) than in Kaweshkar (8.7%) during the contact period. None of these analyses distinguished between abscesses, cysts, and granulomas. Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) diseases seem to have been a recurring health issue among the sampled populations. From a sample of skeletons from Tierra del Fuego, Constantinescu (1999) mentioned a high frequency of TMJ surfaces, although without offering quantitative data. In an earlier paper, Castro and Aspillaga (1991) show a similar prevalence of osteoarthritis of TMJ in Kaweshkar (17%) and Selk’nam (14%) individuals from the mission on Isla Dawson. In a more recent study, Suby and Giberto (2018) analyzed 25 skulls from pre- and postcontact periods from Southern Patagonia following current criteria (Rando and Waldron 2012). The authors found a frequency of 28% of slight osteoarthritis of TMJ (Figure 3), mostly related to AMTL and older age. Consumption of terrestrial resources in the diet was Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 181.31.179.8, on 06 Apr 2020 at 15:27:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5 8 LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY Figure 3. Temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis in Skeleton 2 from the site of Orejas de Burro (Color online). not excluded as a possible related factor. No condylarchanges were identified in this particular study. Systemic Stress and Metabolic Diseases Most studies of systemic stress were designed to analyze the presence of cribra orbitalia, porotic hyperostosis, and dental enamel hypoplasia; they exhibited variable results. In most cases, the authors did not report their diagnostic methods. Among the most important studies, Pérez-Pérez and Lalueza Fox (1992) identified a frequency of the occurrence of cribra orbitalia of 12.75% in a total of 207 skulls, all slight and without significant differences between ethnic groups, sex, or age. Guichón (1994) analyzed cribra orbitalia in 54 skulls mainly from Tierra del Fuego (Table 3). In that sample, 40% showed at least one orbit affected. Moreover, all nonadults presented lesions. In 12 skeletons from Bahía Valentín (the southeastern extreme of Tierra del Fuego), Kozameh and colleagues (2000) reported the absence of porotic hyperostosis and cribra orbitalia. Later, Schinder and Guichón (2003) analyzed porotic syndrome in skulls from Tierra del Fuego. Five of six individuals (83%) with terrestrial diets and all of the three skeletons with marine diet exhibited cribra orbitalia. They found no relationship between porotic syndrome and the dietary patterns described for populations from Tierra del Fuego, although these results could be biased by the small size of the sample. In their study of skeletal remains from Isla Navarino (Chile), Aspillaga and others (1999) mentioned a high frequency of porotic hyperostosis in individuals with maritime economies, but once again, no quantitative data were reported. The authors suggested that porotic syndrome could be caused by parasites associated with the consumption of fish and marine mammals; they urged caution when interpreting porotic syndrome as being caused by anemia (e.g., McIlvaine 2015; Walker et al. 2009). More recently, Suby (2014a) identified a frequency of 40% of porotic hyperostosis and 7.5% of cribra orbitalia in 40 skeletons from Southern Patagonia; most cases were of low severity, following the diagnostic criteria proposed by Stuart-Macadam (1985). Porotic hyperostosis was more prevalent in individuals with marine and mixed diets (66.7% and 62.5%, respectively) than in those with a terrestrial diet (15%). On the contrary, cribra orbitalia affected 3 of the 12 (25%) individuals with marine diets and none of those with terrestrial or mixed diets. A recent study of skeletons buried at the cemetery of the “La Candelaria” mission (Rio Grande, Tierra del Fuego), showed a prevalence of 92% of porotic hyperostosis and 23% of cribra orbitalia in adult individuals (García Laborde 2017). These frequencies are higher than those found by Guichón (1994) and Suby (2014a) in samples from Northern Tierra del Fuego. Suby (2014a) suggested that Native– European contact in Southern Patagonia could have had a more important impact on the health of individuals who lived in missions than on those who did not. In a similar way, Suby and others (2013) reported that females older than 25 years old from the La Candelaria mission showed bone loss in the hips and lumbar vertebrae that could be interpreted to be osteopenia, which could be related to nutritional deficits in that historical context. Finally, studies of dental enamel hypoplasia presented by Pérez-Pérez and Lalueza Fox (1992) showed a prevalence of 55% of individuals affected, without significant differences between sexes and ages. Guichón (1994) also found a prevalence of 42% in 26 skeletons Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 181.31.179.8, on 06 Apr 2020 at 15:27:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5 [Suby] PALEOPATHOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN SOUTHERN PATAGONIA 9 Table 3. Prevalence of Cribra Orbitalia (CO) and Porotic Hyperostosis (PH) in Skeletal Samples from Southern Patagonia. Reference Pérez-Pérez and Lalueza Fox 1992 Guichón 1994 Kozameh et al. 2000 Suby 2014a García Laborde 2017 Sample Chronology Southern Patagonia (n = 207) Southern Patagonia (n = 54) Southeastern Tierra del Fuego (n = 12) Southern Patagonia (n = 40) ND ND ND Precontact (n = 19) and postcontact (n = 21) Salesian Mission of Rio Grande, Northern Postcontact Tierra del Fuego (n = 13) from Tierra del Fuego, without a difference between the sexes. In contrast, Kozameh and colleagues (2000) did not find this condition in skeletons from Bahia Valentín, in the oriental extreme of Tierra del Fuego. Degenerative Joint Disease, Enthesic Changes, and Bone Cortical Geometry Only a few detailed studies on degenerative joint disease and enthesic changes have been conducted from skeletal samples of Southern Patagonia. Contantinescu (1997, 1999) found enthesic changes in the superior limbs of Selk’nam caused by flexion, extension, and rotation of the arms related to archery for hunting, and in lower limbs probably associated with walking. Moreover, Constantinescu (1999) studied 32 skeletons from Tierra del Fuego, most of which were incomplete, describing the highly developed entheses of limbs possibly associated with rowing and transport of heavy loads. These studies neither quantified the results nor mentioned the methods used to identify and record entheseal changes. The most detailed study of enthesic changes in Southern Patagonia was conducted by Zúñiga Thayer (2016), who studied a sample of 26 skeletons from Southern Tierra del Fuego using the method proposed by Villotte and Knüsel (2013). This study also showed more highly developed enthesic changes in the upper limbs of female skeletons, interpreted as evidence of repeated rowing during the lifetime of these individuals. Regarding the geometry of long bones, Pearson and Millones (2005) reported high robusticity in lower and upper limbs in Selk’nam and Yamana individuals, without differences between the populations and at similar rates to other populations adapted to high latitudes. In CO PH 12.75% 40% 0% 7.5% ND ND 0% 40% 23% 92% contrast, Suby (2007), Suby and Guichón (2009), and Suby and Novellino (2017) showed that individuals with marine lifestyles from Tierra del Fuego have a higher cross-sectional geometry of tibias and femoral robusticity than those with terrestrial and mixed lifestyles. Nevertheless, the small sample sizes of these studies need to be considered when comparing these results to studies using a larger sample of skeletons. Regarding degenerative joint disease, Suby (2014b) showed that adult individuals from the Santa Cruz/Magallanes region presented a higher prevalence of Schmorl’s nodes (62.5%) than the skeletons from Northern (12.5%) and Southern (0%) Tierra del Fuego. The frequency of Schmorl’s nodes was higher in the precontact sample (36.4%; n = 4/11) than in the postcontact sample (18.2%; n = 2/11). Nevertheless, no statistical difference was found between the chronological samples. In contrast, skeletons from individuals with a terrestrial diet exhibited a statistically higher prevalence of Schmorl’s nodes (50%) than individuals with mixed (16.6%) and marine (0%) diets. The differences were associated with greater mechanical stress on the lower vertebrae, although congenital morphological differences are also a possibility. That same study found no relationship between vertebral osteophytes and Schmorl’s nodes (Suby 2014b). Likewise, D’Angelo and colleagues (2017) showed that spondylolysis was present in 7 of 35 (20%) skeletons in a sample from Southern Patagonia. A lower frequency was identified in the precontact sample (11.1%; n = 1/9) than in the contact-period sample (23.1%; n = 6/26), which the authors suggested was due to be the negative effects of European contact on the lifestyle of native populations. Finally, Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 181.31.179.8, on 06 Apr 2020 at 15:27:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5 10 LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY Zúñiga Thayer and others (2018) studied the prevalence of osteochondritis dissecans in 26 skeletons from Southern Patagonia: 42.3%— mostly those from individuals with terrestrial diets—exhibited at least one lesion. Moreover, 66.6% of the lesions were identified in the glenoid cavity of the scapulae, more frequently of the right arm, probably related to mechanical stress. Trauma and Violence Trauma and interpersonal violence are scarcely reported in skeletal remains from Southern Patagonia, but no systematic research has been carried out so far (Prieto and Cardenas 2007). Among the clearest cases of violence was a nonradiocarbon-dated skull of an Aonikenk male from Santiago Bay in the northern coast of the Strait of Magellan (Chile), with a green obsidian projectile fragment encrusted in the right temporal bone (Constantinescu 2003). Considering the new bone formation described, the individual could have survived the episode. Also in Southern continental Patagonia, L’Heureux and Amorosi (2009) described cranial traumatic lesions in skeletons CL.2.1 and CL.3 recovered from the site Cañadón Leona 5 (Magellan Region, Chile), assigned to about 1740–2280 years BP from vegetal charcoal; these lesions were interpreted as evidence of interpersonal violence. The first individual, a young/middle-aged adult male, presented a circular hole of about 15 mm in the left parietal bone. The second skeleton, a middle-aged adult female, exhibited a large traumatic lesion in the left temporal and parietal bones, assumed by the authors to be the cause of death (L’Heureux and Amorosi 2009). In Tierra del Fuego, Suby and others (2008) identified three circular traumatic lesions without new bone formation in the skull of a skeleton recovered from the Puesto Pescador 1 site (Atlantic coast of Tierra del Fuego), dated to 335 ± 35 years BP; these lesions were attributed to a violent episode. Finally, Suby and Guichón (2010) reported two cases of interpersonal violence in remains of the skeletal commingled collection housed in the Salesian Mission La Candelaria (Rio Grande, Tierra del Fuego). One of them is an adult male pelvis with two lithic projectile fragments encrusted in both iliac bones, one of which probably compromised the abdominal organs. The absence of bone remodeling suggested that it is a perimortem lesion. The second case is a skull with a lithic projectile of 15 mm of length in the right parietal, also assumed to be perimortem due to lack of new bone formation surrounding the projectile. Unfortunately, neither of these two skeletons have detailed archaeological and chronological information. Trauma was reported mainly in the ribs, with fractures reported in the skeletons recovered from Rincón del Buque (Suby et al. 2009) and Orejas de Burro (L’Heureux and Barberena 2008), both in Southern continental Patagonia. Kozameh and colleagues (2000) also described a humeral fracture in a skeleton from the Bahia Valentín site (Southern Tierra del Fuego). Suby (2014c) showed that among 25 adult skeletons, 9 (36%) exhibited bone fractures, equally distributed among the ribs, vertebrae, and long bones. Only three cases of vertebral fractures were described. Among them, a Jefferson’s fracture of the atlas was diagnosed in a prehistoric skeleton from the Shamakush Entierro archaeological site from the Beagle Channel (Suby et al. 2011). Nevertheless, no specific studies were conducted on this type of fracture. Recently, Flensborg and Suby (2020) reviewed and analyzed the reported traumas in skeletal human remains from Southern Patagonia. Of a total sample of 126 skeletons, 15 (11.9%) adult individuals were affected by trauma. Most lesions were antemortem, produced by accidents or violence, and were more frequent in Santa Cruz/Magallanes and the north of Tierra del Fuego than in the south of Tierra del Fuego. Discussion The paleopathological analyses of human skeletal remains from Southern Patagonia have remarkably advanced during the last two decades. The studies have evolved from a descriptive to an analytic approach, based on some of the most recent theoretical and methodological advances. Nevertheless, paleopathological research still follows the same pattern observed in other countries, in which case studies still dominate (Hens and Godde 2008). In spite of the increase in available information, there are Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 181.31.179.8, on 06 Apr 2020 at 15:27:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5 [Suby] PALEOPATHOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN SOUTHERN PATAGONIA few integrative studies of stress and disease patterns. Here I attempt to fill that gap, offering a review of the most relevant results to make them more widely available to biarchaeological and archaeological discussions. Some patterns in disease and stress can be identified in available data, but evidence of infectious diseases is still too scarce to propose a clear pattern. Relatively few bone lesions associated with infections have been reported. Nevertheless, this lack of data cannot be assumed to be evidence of the low prevalence of infectious diseases in past populations, considering that many of them could not be observed in the skeleton because of their biological characteristics, their acute time of evolution, the immune resistance of the host, or their interpretation from skeletal material. Recent reports of molecular, historical and osteological data suggest the presence of tuberculosis (Casali et al. 2006; García Laborde et al. 2010) and treponematosis (Castro and Aspillaga 1991) in prehistoric times, but more frequently in the postcontact period. Nevertheless, more convincing evidence is needed in most of the cases, particularly in skeletons from precolumbian times. Future research needs to focus on potential zoonotic sources of tuberculosis, particularly from seals and sea lions, as suggested by Bos and others (2014) and Bastida and colleagues (2011). The interpretation of infectious diseases also has to integrate other independent lines of evidence, such as those related to mobility and demography of human populations. The archaeological record suggests not only that populations were small in size and limited by biogeographic barriers but also recognizes corridors of exchange of individuals, information, and tools (Martin and Borrero 2017). The isolation restricted the dispersion of infections outside the affected populations, but contact between some groups could widen the geographic distribution of infectious agents. No evidence is yet available regarding these hypothetical epidemiological scenarios. Further research must be conducted. Paleopathological information about infectious diseases, including research into ancient pathogens using new molecular methods, could offer valuable information on the social 11 dynamics of the archaeological record. As an example, multiple burials were interpreted to be indicators of population growth in southern continental Patagonia (Barberena 2008). Nevertheless, these burial sites could also be the result of local increasing mortality. More paleopathological and paleodemographic research would allow archaeologists to discuss the dynamics of change in human populations. All studies of oral disease showed high degrees of dental wear and a low prevalence of caries and antemortem tooth loss, particularly in precontact remains. Terrestrial dietary patterns, especially in the continent and in Northern Tierra del Fuego, probably led to higher mechanical masticatory forces than diets based in marine resources, as is suggested in studies of TMJ osteoarthritis. Food processing could be a relevant factor in the development of oral diseases in precontact times and possibly of other diseases, such as parasitic zoonosis. Lifestyles changes produced in the postcontact period, particularly but not exclusively for those who lived in missions and farms, could be major sources of change in diet and corresponding oral diseases. None of these factors have been extensively studied and should be the focus of further research. Studies of some of the biggest samples did not include the most recent methods and criteria for studying oral pathology, such as caries, enamel hypoplasia, periodontal disease, and periapical infections. Analyses of chronological, sexual, and age-related variability are also needed and should be explored. Evidence of porotic syndrome seems to be more frequent in individuals with marine and mixed economies from Southern and Northern Tierra del Fuego; perhaps it is more closely associated with nutritional effects and parasitic infectious diseases than with dietary iron deficiency (Suby 2014a). Porotic syndrome was possibly more prevalent in populations that inhabited the missions and may be attributed to changes in dietary patterns and lifestyle, such as low consumption of proteins and high consumption of carbohydrates (Castro and Aspillaga 1991; García Laborde et al. 2010). In most of the studies, porotic syndrome was assumed to be caused by iron-deficiency anemia, even though the link between both conditions has recently been Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 181.31.179.8, on 06 Apr 2020 at 15:27:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5 12 LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY criticized and remains unclear (McIlvaine 2015; Walker et al. 2009). Thus, the interpretation of porotic syndrome needs to be more cautious, and new insights have to be considered. Osteopenia was also observed in the skeletons recovered from a mission, although the studied samples were very small; more such studies will allow for more critical evaluation of these results. Studies of pathological fractures in vertebrae, caused by osteoporosis, will help us understand the possible impact of lifestyle change during the contact period. Other metabolic diseases, such as osteomalacia, rickets, and scurvy, remain unexplored in skeletal remains from Southern Patagonia. Data also suggest that individuals living in terrestrial economies from southern continental Patagonia probably experienced higher mechanical skeletal stress on the spine, producing degenerative joint disease in vertebrae, particularly Schmorl’s nodes and vertebral osteophytosis, than did individuals from Tierra del Fuego. Nevertheless, more information is required to evaluate the possible association between degenerative joint disease and age, stature, and body mass. Research into degenerative joint disease in the appendicular skeleton has to be developed, considering that it has only been studied in some skeletons. These analyses will offer additional insight to clarify whether degenerative joint disease could be related to activity in these societies. Similarly, enthesic changes were rarely considered. A recent review of this topic, including the data reported in Argentina, was published by Zúñiga Thayer and Suby (2019). The results reported in Southern Patagonia need to be revisited with recent methods, given that those previously used were criticized for their lack of correlation with clinical and biological data (Henderson et al. 2016). Evidence of violence and trauma is scarce and exclusively derived from individual case studies. Research into traumatic injuries of large samples associated with violence will be helpful in interpreting the possible paleodemographic changes produced during the Late Holocene and in responses to changes in climate and the availability of resources. Although violent episodes seem to be more common in the continent and in Northern Tierra del Fuego than in Southern Tierra del Fuego, attributed by some authors to population increase (e.g., L’Heureux and Amorosi 2009), the geographical distribution of trauma and its interpretation need more extended study. Conclusion and Future Directions Taking into account all these results, stress and disease probably did not affect human societies throughout Southern Patagonia in the same way. Different geographic and cultural human groups exhibited different patterns of degenerative, systemic, and traumatic stress; populations from the continent and from Northern and Southern Tierra del Fuego differed from each other, and these differences were possibly related to their cultural and economic systems. Even though most of the results are incomplete and new research is necessary, all the data obtained so far seem to be consistent with the main pattern observed in other hunter-gatherers (Cohen and Crane-Kramer 2007): a low frequency of oral pathologies and little evidence of infectious diseases. Moreover, Native–European contact could have produced the increase in stress and disease, particularly in those contexts related to missions, although again, more data are needed in this respect. From this analysis, three main concerns relating to paleopathological information from Southern Patagonia can be identified. First, larger samples are needed in almost all lines of research. Because of the absence of cemeteries from precontact periods and the circumstances in which collections were formed (Supplemental Text 1), only a small number of skeletons with archaeologically controlled information are available for bioarchaeological and paleopathological research. Thus, only a few skeletons have chronological data associated with them (Suby et al. 2017). The osteological collections housed in museums have not yet been fully examined, and there remains much information that could be obtained from them; some of these data were included in recent studies. Thus, further analyses are needed to produce more paleodietary, chronological, and paleopathological data from these collections. Second, paleopathological research studies use different methodological approaches, which makes comparisons between results particularly Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 181.31.179.8, on 06 Apr 2020 at 15:27:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5 [Suby] PALEOPATHOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN SOUTHERN PATAGONIA challenging. Data from the 1990s obviously are not compatible with the methods for registration and diagnosis of oral and bone diseases available today. Much of these data need to be reexamined with more current methods. For that reason, some of the patterns derived from comparisons among studies suggested here need to be taken with extreme caution and are likely to be adjusted in the future. Finally, many bone and oral diseases were scarcely explored in skeletons from Southern Patagonia, whereas many others were not evaluated at all. For example, degenerative joint disease was studied only in small samples, particularly in the spine and the appendicular skeleton in some preliminary research. Traumatic, infectious, and congenital diseases were mostly treated in descriptive case studies and need to be specifically studied in skeletal samples. Moreover, metabolic disease such as osteopenia and osteoporosis was only studied in a few skeletons and needs to be more widely analyzed. Neoplastic diseases were not reported, but neither were they the aim of any particular research. New methods, such as the investigation of ancient pathogen genomics by next-generation sequencing, are mostly unexplored in skeletal remains from Patagonia and need to be included in future paleopathological research. Human stress and disease are strongly influenced by behavior, socioeconomic organization, demography, and environmental resources. Bearing in mind the complex relationship among these multiple factors, future paleopathological researches of hunter-gatherers from Southern Patagonia must include a wider range of information than skeletal data. Archaeological and paleoenvironmental studies produced high amounts of information from this region that are waiting to be analyzed undera paleopathological approach. Only paleopathology is capable of providing information on the effects of peopling, adaptation, and mobility on the health of hunter-gatherer human populations from Southern Patagonia. The integration of this knowledge will be one of the major challenges for the future. Acknowledgments. I would like to express my gratitude to Luis Borrero, Leandro Luna, and Claudia Aranda for their kind comments on a previous version of this article. Thank 13 you to the editors and the three anonymous reviewers who helped improve this article through their comments. This research was founded by Grant PICT 0358-2008 and PICT 0191-2016 (National Agency for Scientific and Technological Research, Argentina) and CONICET-PIP 2015-11220150100016CO. Also thanks to Sandra Baliño for her linguistic assistance. Data Availability Statement. All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article and in the articles detailed in the references. Supplemental Material. For supplementary material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5. Supplemental Text 1. Environmental, Ethnographic, and Archaeological Context. References Cited Alfonso-Durruty, Marta P., Elisa Calás, and Flavia Morello 2011 Análisis Bioantropológico de un Enterratorio Humano del Holoceno Tardío en Cabo Nose, Tierra Del Fuego, Chile. Magallania 39(1):147–162. Araújo, Adauto, Karl Reinhard, Daniela Leles, Luciana Sianto, Alena M. Iñiguez, Martín H. Fugassa, Bernardo Arriaza, Nancy Orellana, and Luis F. Ferreira 2011 Paleoepidemiology of Intestinal Parasites and Lice in Pre-Columbian South America. Chungara 43: 303–313. Aspillaga, Eugenio, and Carlos Ocampo 1996 Restos Óseos Humanos de la Isla Karukinka (Seno Almirantazgo, Tierra del Fuego): Informe Preliminar. Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia 24:153–161. Aspillaga, Eugenio, Carlos Ocampo, and Pilar Rivas 1999 Restos Óseos Humanos de Contextos Arqueológicos del Área de Navarino: Indicadores de Estilo de Vida en Indígenas Canoeros. Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia 26:123–136. Barberena, Ramiro 2008 Arqueología y Biogeografía Humana en Patagonia Meridional. Sociedad Argentina de Antropología, Buenos Aires. Bastida, Ricardo, Viviana Quse, and Ricardo Guichón 2011 La Tuberculosis en Grupos de Cazadores Recolectores de Patagonia y Tierra del Fuego: Nuevas Alternativas de Contagio a Través de la Fauna Silvestre. Revista Argentina de Antropología Biológica 13(1):83–95. Bos, Kirsten I., Kelly M. Harkins, Alexander Herbig, Mireia Coscolla, Nico Weber, Iñaki Comas, Stephen A. Forrest, Josephine M. Bryant, Simon R. Harris, Verena J. Schuenemann, Tessa J. Campbell, Kerttu Majander, Alicia K. Wilbur, Ricardo A. Guichón, Daniel L. Wolfe Steadman, Della C. Cook, Stefan Niemann, Marcel A. Behr, Martin Zumarraga, Ricardo Bastida, Daniel Huson, Kay Nieselt, Douglas Young, Julian Parkhill, Jane E. Buikstra, Sebastien Gagneux, Anne C. Stone, and Johannes Krause 2014 Pre-Columbian Mycobacterial Genomes Reveal Seals as a Source of New World Human Tuberculosis. Nature 514:494–497. Casali, Romina, Martín H. Fugassa, and Ricardo A. Guichón 2006 Aproximación Epidemiológica al Proceso de Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 181.31.179.8, on 06 Apr 2020 at 15:27:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5 14 LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY Contacto Interétnico en el Norte de Tierra del Fuego. Magallania 34(1):87–101. Castro, Mario, and Eugenio Aspillaga 1991 Fuegian Paleopathology. Antropología Biológica 1:1–13. Castro, Alicia, Susana Salceda, Marcos Plischuk, and Bárbara Desántolo 2008 Bioarqueología de Rescate: Sitio Carsa (Costa Norte de Santa Cruz, Argentina). In Arqueología de Patagonia: Una Mirada desde el Último Confín, edited by Mónica Salemme, Fernando Santiago, Myriam Álvarez, Ernesto Piana, Martín Vázquez, and María E. Mansur, pp. 629–638. Utopías, Ushuaia. Cohen, Mark N. 2009 Introduction: Rethinking the Origins of Agriculture. Current Anthropology 50:591–595. Cohen, Mark N., and George Armelagos 1984 Palaeopathology at the Origins of Agriculture. University Press of Florida, Gainesville. Cohen, Mark N., and Gillian M. M. Crane-Kramer 2007 Editors’ Summation. In Ancient Health: Skeletal Indicators of Agricultural and Economic Intensification, edited by Mark N. Cohen and Gillian M. M. Crane-Kramer, pp. 320–343. University Press of Florida, Gainesville. Constantinescu, Florence 1997 Hombres y Mujeres de Cerro los Onas: Presentes, Ausentes… Los Relatos de los Huesos. Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia 25:59–74. 1999 Evidencias Bioantropológicas para Modos de Vida Cazador Recolector Terrestre y Marítimo en los Restos Óseos Humanos de Tierra del Fuego. Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia 27:137–174. 2003 Obsidiana Verde Incrustada en un Cráneo Aoinikenk: Tensión Social Intraétnica . . . o Interétnica? We’ll Never Know! Magallania 31:149–153. D’Angelo del Campo, Manuel, Jorge A. Suby, Pamela García Laborde, and Ricardo A. Guichón 2017 Spondylolysis in the Past: A Case Study of HunterGatherers from Southern Patagonia. International Journal of Paleopathology 19:1–17. Domett, Kate, and Nancy Tayles 2007 Population Health from the Bronze to the Iron Age in the Mun River Valley, Northeastern Thailand. In Ancient Health: Skeletal Indicators of Agricultural and Economic Intensification, edited by Mark N. Cohen and Gillian M. M. Crane-Kramer, pp. 286–299. University Press of Florida, Gainesville. Flensborg, Gustavo, and Jorge Suby 2020 Trauma y violencia en Patagonia Austral: Interpretación de evidencias bioarqueológicas y perspectivas futuras. Chungara, in press. DOI:10.4067/ S0717-73562020005000101. Fugassa, Martín H. 2006 Enteroparasitosis en Poblaciones CazadorasRecolectoras de Patagonia Austral. PhD dissertation, Department of Biology, Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Buenos Aires. 2015 Checklist of Helminths Found in Patagonian Wild Mammals. Zootaxa 4012:271–328 Fugassa, Martín H., Aarmando Cicchino, Norma Sardella, Ricardo A. Guichón, Guillermo Denegri, and Adauto Araújo 2007 Nuevas Fuentes de Evidencia para la Paleoparasitología y la Antropología Biológica en Patagonia. Revista Argentina de Antropología Biológica 9(2):51–57. Fugassa, Martín, Guillermo Denegri, Norma Sardella, Adauto Araújo, Ricardo A. Guichón, Pablo A. Martínez, María T. Civalero, and Carlos Aschero 2006 Paleoparasitological Records in Canid Coprolite from Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Parasitology 92:1110– 1113. Fugassa, Martín H., Norma Sardella, Ricardo A. Guichón, Guillermo Denegri, and Adauto Araújo 2008 Paleoparasitological Analysis Applied to MuseumCurated Sacra from Meridional Patagonian Collections. Journal of Archaeological Science 35:1408–1411. García Guraieb, Solana 2006 Salud y Enfermedad en Cazadores-Recolectores del Holoceno Tardío en la Cuenca del Lago Salitroso (Santa Cruz). Intersecciones en Antropología 7:37–48. García Guraieb, Solana, Valeria Bernal, Paula González, Luis Bosio, and Ana M. Aguerre 2009 Nuevos Estudios del Esqueleto del Sitio Cerro Yanquenao (Colhue Huapi, Chubut): Veintiocho Años Después. Magallania 37(2):165–175. García Guraieb, Solana, Rafael Goñi, and Augusto Tessone 2015 Paleodemography of Late Holocene HunterGatherers from Patagonia (Santa Cruz, Argentina): An Approach Using Multiple Archaeological and Bioarchaeological Indicators. Quaternary International 356:147–158. García Laborde, Pamela 2017 Estado Nutricional de la Población Selk’nam: Aproximación Bioarqueológica al Impacto Generado por la Misionalización. Misión Salesiana Nuestra Señora de La Candelaria, Tierra del Fuego (Siglos XIX–XX). PhD dissertation, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad Nacional del Centro de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires. García Laborde, Pamela, Jorge A. Suby, Ricardo A. Guichón, and Romina Casali 2010 El Antiguo Cementerio de la Misión de Río Grande, Tierra del Fuego: Primeros Resultados sobre Patologías Nutricionales-Metabólicas e Infecciosas. Revista Argentina de Antropología Biológica 12:57–69. Goñi, Rafael, Luis Bosio, and Solana García Guraieb 2003–2005 Un Caso de Enfermedad Infecciosa en Cazadores-Recolectores Prehispánicos de Patagonia. Cuadernos del Instituto Nacional de Antropología y Pensamiento Latinoamericano 20:399–404. Guichón, Ricardo A. 1994 Antropología Física de Tierra del Fuego. Caracterización Biológica de las Poblaciones Prehispánicas. PhD dissertation, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires. Guichón, Ricardo A., Jane E. Buikstra, Anne Stone, Kelly Harkins, Jorge A. Suby, Mauricio Massone, Alfredo Prieto, Alicia Wilbur, Florence Constantinescu, and Conrado Rodríguez Martín 2015 Pre-Columbian Tuberculosis in Tierra del Fuego? Discussion of Paleopathological and Molecular Evidence. International Journal of Paleopathology 11:92–101. Guichón, Ricardo A., and Jorge A. Suby 2011 Estudio Bioarqueológico de los Restos Humanos Recuperados por Anne Chapman en Caleta Falsa, Tierra del Fuego. Magallania 39(1):163–177. Henderson, Charlotte Y., Valentina Mariotti, Doris PanyKucera, Sebastien Villotte, and Cynthia Wilczak 2016 The New “Coimbra Method”: A Biologically Appropriate Method for Recording Specific Features Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 181.31.179.8, on 06 Apr 2020 at 15:27:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5 [Suby] PALEOPATHOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN SOUTHERN PATAGONIA of Fibrocartilaginous Entheseal Changes. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 26:925–932. Hens, Samantha M., and Kanya Godde 2008 Brief Communication: Skeletal Biology Past and Present: Are We Moving in the Right Direction? American Journal of Physical Anthropology 137:234–239. Jackes, Mary, David Lubell, and Christopher Meiklejohn 1997 Healthy but Mortal: Human Biology and the First Farmers of Western Europe. Antiquity 71:639–658. Klaus, Haagen D., and Rosabella Alvarez-Calderón 2017 Escaping Conquest? A First Look at Regional Cultural and Biological Variation in Postcontact Eten, Peru. In Colonized Bodies, Worlds Transformed: Toward a Global Bioarchaeology of Contact and Colonialism, edited by Melissa S. Murphy and Haagen D. Klaus, pp. 95–128. University Press of Florida, Gainesville. Kozameh, Livia, and Ana M. Benítez 2005 Diversos Usos Instrumentales del Aparato Masticatorio en Restos Humanos de la Patagonia Argentina. Revista Argentina de Antropología Biológica 7(1):124. Kozameh Livia, Juan E. Barbosa, and Hernán Vidal 2000 Los cazadores de Bahía Valentín, Tierra del Fuego: Su status de salud y enfermedad. In Desde el País de los Gigantes: Perspectivas arqueológicas en Patagonia, edited by Silvana Espinosa, pp. 123–140. Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia Austral, Río Gallegos, Patagonia. Larsen, Clark. S. 2001 Bioarchaeology of Spanish Florida: The Impact of Colonialism. University Press of Florida, Gainesville. Larsen, Clark S., and George R. Milner 1994 In the Wake of Contact: Biological Responses to Conquest. Wiley-Liss, New York. L’Heureux, Lorena, and Tomas Amorosi 2009 El Entierro 2 del Sitio Cañadón Leona 5 (Región de Magallanes, Chile). Viejos Huesos, Nuevos Datos. Magallania 37(2):41–55. 2010 El Entierro del Sitio Cerro Sota (Magallanes, Chile) a Más de Setenta Años de su Excavación. Magallania 38(2):133–149. L’Heureux, Lorena, and Ramiro Barberena 2008 Evidencias Bioarqueológicas en Patagonia Meridional: el Sitio Orejas de Burro 1 (Pali Aike, Provincia de Santa Cruz). Intersecciones en Antropología 9:11–24. L’Heureux, Lorena, Ricardo A. Guichón, Ramiro Barberena, and Luis Borrero 2003 Durmiendo Bajo el Faro: Estudio de un Entierro Humano en Cabo Vírgenes (C.V.17), Pcia. de Santa Cruz, República Argentina. Intersecciones en Antropología 4:87–98. Luna, Leandro, and Jorge A. Suby 2014 Recent Advances in Palaeopathology and the Study of Past Societies in Argentina, Southern South America. Anthropological Science 122:53–54. Martin, Fabiana, and Luis Borrero 2017 Climate Change, Availability of Territory, and Late Pleistocene Human Exploration of Última Esperanza, South Chile. Quaternary International 428:86–95. McIlvaine, Britney 2015 Implications of Reappraising the Iron-Deficiency Anemia Hypothesis. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 25:997–1000. Molnar, Stephen 1971 Human Tooth Wear, Tooth Function and Cultural 15 Variability. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 34:175–189. Moreno, Eduardo, Atilio F. Zangrando, Augusto Tessone, Alicia Castro, and Horacio Panarello 2011 Isótopos Estables, Fauna y Tecnología en el Estudio de los Cazadores-Recolectores de la Costa Norte de Santa Cruz. Magallania 39(1):265–276. Murphy, Melissa S., and Haagen D. Klaus 2017 Transcending Conquest: Bioarchaeological Perspectives on Conquest and Culture Contact for the TwentyFirst Century. In Colonized Bodies, Worlds Transformed: Toward a Global Bioarchaeology of Contact and Colonialism, edited by Melissa S. Murphy and Haagen D. Klaus, pp. 1–38. University Press of Florida, Gainesville. Pandiani, Cynthia D., Jorge A. Suby, and Ana L. Santos 2018 Exostosis Auditiva Externa en Individuos Adultos del Holoceno Tardío (1500 AP–Siglo XIX) en Patagonia Austral. Revista Argentina de Antropología Biológica 21(1). DOI:https://doi.org/10.17139/raab.2019. 0021.01.05. Pearson, Osborn, and Mario Millones 2005 Rasgos Esqueletales de Adaptación al Clima y a la Actividad Entre los Habitantes Aborígenes de Tierra del Fuego. Magallania 33(1):37–50. Pérez-Pérez, Alejandro, and Carlos Lalueza-Fox 1992 Indicadores de Presión Ambiental en Aborígenes de Fuego-Patagonia: Reflejo de la Adaptación a Un Ambiente Adverso. Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia 21:99–108. Ponce, Paola, Gabriela Ghidini, and Rolando González-José 2008 External Auditory Exostosis “at the End of the World”: The Southernmost Evidence According to the Latitudinal Hypothesis. In Proceedings of the Eighth Annual Conference of the British Association for Biological Anthropology and Osteoarchaeology, edited by Megan Brickley and Shannon M. Smith, pp. 101–107. BAR International Series 1743. Archaeopress, Oxford. Prieto, Alfredo, and Rodrigo Cárdenas 2007 The Struggle for Social Life in Fuego-Patagonia. In Latin American Indigenous Warfare and Ritual Violence, edited by Richard J. Chacon and Rubén G. Mendoza, pp. 212–233. University of Arizona Press, Tucson. Rando, Carolyn, and Tony Waldron 2012 TMJ Osteoarthritis: A New Approach to Diagnosis. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 148:45–53. Ribot Isabelle, Alan G. Morris, and Emily S. Renschler 2017 Effects of Colonialism from the Perspective of Craniofacial Variation: Comparing Case Studies Involving African Populations. In Colonized Bodies, Worlds Transformed: Toward a Global Bioarchaeology of Contact and Colonialism, edited by Melissa S. Murphy and Haagen D. Klaus, pp. 339–374. University Press of Florida, Gainesville. Roberts, Charlotte A. 2015 What Did Agriculture Do for Us? The Bioarchaeology of Health and Diet. In A World with Agriculture, 12,000 BCE–500 CE, edited by Graeme Barker, and Candice Goucher, pp. 93–123. Cambridge World History Vol. 15. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 2016 Palaeopathology and Its Relevance to Understanding Health and Disease Today: The Impact of the Environment on Health, Past and Present. Anthropological Review 79:1–16. Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 181.31.179.8, on 06 Apr 2020 at 15:27:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5 16 LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY 2019 Infectious Disease: Introduction, Periostosis, Periostitis, Osteomyelitis, and Septic Arthritis. In Ortner’s Identification of Pathological Conditions in Human Skeletal Remains, edited by Jane Buikstra, pp. 285– 320. Academic Press, London. Rodríguez Balboa, Mónica, Eugenio Aspillaga, and Baruch Arensburg 2014 El Estudio Bioantropológico de las Colecciones Esqueletales del Archipiélago de Chiloé: Perspectivas y Limitaciones. In Avances Recientes en la Bioarqueología Latinoamericana, edited by Leandro Luna, Claudia Aranda, and Jorge A. Suby, pp. 269–277. Grupo de Investigaciones en Bioarqueología, Buenos Aires. Pinhasi Ron, and Jay T. Stock 2011 Human Bioarchaeology of the Transition to Agriculture. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester. Sáez, Arturo 2008 Impacto del Contacto Hispano-Indígena en la Salud de la Población de Chiloé: Un Caso de Tuberculosis en el Cementerio Puqueldon 1. Magallania 36(2):167– 174. Santiago, Fernando, Mónica Salemme, Jorge A. Suby, and Ricardo A. Guichón 2011 Restos Óseos Humanos en el Norte de Tierra del Fuego: Aspectos Contextuales, Dietarios y Paleopatológicos. Intersecciones en Antropología 12:147–162. Schinder, Gala, and Ricardo A. Guichón 2003 Isótopos Estables y Estilo de Vida en Muestras Óseas Humanas de Tierra del Fuego. Magallania 31:33–44. Scott, Eugene C. 1979 Dental Wear Scoring Technique. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 51:213–218. Smith, B. Holly 1984 Patterns of Molar Wear in Hunter-Gatherers and Agriculturalists. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 63:39–56. Standen, Vivien, Bernado Arriaza, and Calogero Santoro 1997 External Auditory Exostosis in Prehistoric Chilean Populations: A Test of the Cold Water Hypothesis. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 103:119–129. Stojanowski, Christopher M. 2013 Mission Cemeteries, Mission Peoples: Historical and Evolutionary Dimensions of Intracemetery Bioarchaeology in Spanish Florida. University Press of Florida, Gainesville. Stuart-Macadam, Patricia 1985 Porotic Hyperostosis: Representative of a Childhood Condition. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 66:391–398. Suby, Jorge A. 2007 Propiedades Estructurales de Restos Óseos Humanos y Paleopatología en Patagonia Austral. PhD dissertation, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Buenos Aires. 2014a Porotic Hyperostosis and Cribra Orbitalia in Human Remains from Southern Patagonia. Anthropological Science 122:69–79. 2014b Nódulos de Schmorl en Restos Humanos Arqueológicos de Patagonia Austral. Magallania 42(1):135– 147. 2014c Desarrollos Recientes en el Estudio de la Salud de las Poblaciones Humanas Antiguas de Patagonia Austral. In Avances Recientes en la Bioarqueología Latinoamericana, edited by Leandro Luna, Claudia Aranda, and Jorge A. Suby, pp. 69–100. Grupo de Investigaciones en Bioarqueología, Buenos Aires. Suby, Jorge A., Sebastián Costantino, Carlos Capiel, María M. Lucarini, and Ezequiel Etchepare 2013 Exploraciones de la Densidad Mineral Ósea y Osteopenia en Poblaciones Humanas Antiguas de Patagonia Austral. Intersecciones en Antropología 14:433–445. Suby, Jorge A., and Diego A. Giberto 2018 Temporomandibular Joint Osteoarthritis in Human Ancient Skeletal Remains from Late Holocene in Southern Patagonia. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 29:14–25. Suby, Jorge A., and Ricardo A. Guichón 2009 Diet, Nutrition and Paleopathology in Southern Patagonia: Some Experiences and Perspectives. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 19:328–336. 2010 Los Restos Óseos Humanos de la Colección de la Misión “La Candelaria” (Rio Grande, Tierra Del Fuego). Magallania 38(2):121–133. Suby, Jorge A., Ricardo A. Guichón, and Atilio F. Zangrando 2009 El Registro Biológico Humano de la Costa Meridional de Santa Cruz. Revista Argentina de Antropología Biológica 11(1):109–124. Suby, Jorge A., Leandro H. Luna, Claudia Aranda, and Gustavo Flensborg 2017 First Approximation to Paleodemography of HunterGatherers from Southern Patagonia during Middle-Late Holocene. Quaternary International 438:174–188. Suby, Jorge A., and Paula Novellino 2017 Análisis Comparativo de la Geometría de la Sección Transversal de Tibias de Restos Humanos de Patagonia Austral y Centro-Norte de Mendoza. Revista Argentina de Antropología Biológica 19(2):1–14. Suby, Jorge A., Mónica Salemme, and Fernando Santiago 2008 Análisis Paleopatológico de los Restos Humanos del Sitio Puesto Pescador 1 (Tierra Del Fuego). Magallania 36(1):53–64. Suby, Jorge A., Atilio F. Zangrando, and Ernesto Piana 2011 Exploraciones Osteológicas de la Salud de las Poblaciones Humanas del Canal Beagle. Relaciones de la Sociedad Argentina de Antropología 36:249–270. Taglioretti, Valeria, Martín H. Fugassa, Diego Rindel, and Normal Sardella 2017 New Parasitological Findings for Pre-Hispanic Camelids. Parasitology 144:1763–1768. Toomay Douglas, Michele, and Michael Pietrusewsky 2007 Biological Consequences of Sedentism Agricultural Intensification in Northeastern Thailand. In Ancient Health: Skeletal Indicators of Agricultural and Economic Intensification, edited by Mark N. Cohen and Gillian M. M. Crane-Kramer, pp. 300–319. University Press of Florida, Gainesville. Verano, John W., and Douglas H. Ubelaker 1992 Disease and Demography in the Americas. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Villotte, Sébastien, and Christopher J. Knüsel 2013 Understanding Entheseal Changes: Definition and Life Course Changes. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 23:135–146. Walker, Phillip, Rondha R. Bathurst, Rebecca Richman, Thor Gjerdrum, and Valerie A. Andrushko 2009 The Causes of Porotic Hyperostosis and Cribra Orbitalia: A Reappraisal of the Iron-Deficiency-Anemia Hypothesis. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 139:109–125. Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 181.31.179.8, on 06 Apr 2020 at 15:27:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5 [Suby] PALEOPATHOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN SOUTHERN PATAGONIA Webb, Steven 1995 Palaeopathology of Aboriginal Australians: Health and Disease across a Hunter-Gatherer Continent. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Weston, Darlene 2012 Non-Specific Infection in Palaeopathology: Interpreting Periosteal Reactions. In A Companion to Paleopathology, edited by Anne Grauer, pp. 492–512. Wiley-Blackwell, New York. Zúñiga Thayer, Rodrigo 2016 Aproximación a la actividad de remo en canoa: Un estudio de cambios entésicos en miembro superior de individuos del antiguo territorio yagan. Degree dissertation, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Concepción, Concepción, Chile. 17 Zúñiga Thayer, Rodrigo, and Jorge A. Suby 2019 El Estudio de los Cambios Entésicos en Restos Humanos de Argentina. Estado Actual y Avances Futuros. Revista Argentina de Antropología Biológica 21(2):003. DOI:https://doi.org/10.24215/18536387e003. Zúñiga Thayer, Rodrigo, Jorge A. Suby, Gustavo Flensborg, and Leandro H. Luna 2018 Osteocondritis Disecante: Primeros Resultados en Restos Humanos de Cazadores-Recolectores del Holoceno en Patagonia Austral. Revista del Museo de Antropología 11(1):107–120. Submitted October 17, 2018; Revised May 29, 2019; Accepted December 3, 2019 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 181.31.179.8, on 06 Apr 2020 at 15:27:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.5 View publication stats