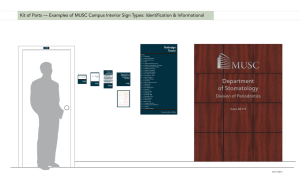

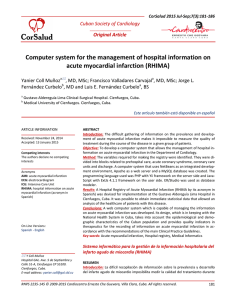

BEYOND THE GUIDELINES Annals of Internal Medicine How Would You Treat This Patient With Gallstone Pancreatitis? Grand Rounds Discussion From Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Anjala Tess, MD; Steven D. Freedman, MD, PhD; Tara Kent, MD; and Howard Libman, MD Acute pancreatitis, a common cause of hospitalization in the United States, is often the result of biliary tract disease. In 2016, the American Gastroenterological Association released a guideline that addresses the practical considerations in managing acute pancreatitis within the first 72 hours after the patient presents. The guideline specifically recommends goal-directed hydration therapy, early enteral feeding, judicious use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and gallbladder surgery during the index admission for patients with mild pancreatitis. The authors discuss their approach to these interventions in the context of a patient with recurrent acute pancreatitis who chooses to delay surgery until after hospital discharge. They address hydration and timing of surgery, as well as how they would manage the patient's preferences in the face of existing guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:175-181. doi:10.7326/M18-3536 For author affiliations, see end of text. M r. R is a 44-year-old man with a surgical history of anterior cruciate ligament repair of the left knee and inguinal herniorrhaphy and an unremarkable medical history. He works as an accountant and does not smoke tobacco or drink alcohol. In October 2017, he had a transient episode of abdominal pain associated with diaphoresis, nausea, and emesis, for which he presented to a local emergency department for evaluation. ABOUT BEYOND THE GUIDELINES Beyond the Guidelines is a multimedia feature based on selected clinical conferences at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC). Each educational feature focuses on the care of a patient who “falls between the cracks” in available evidence and for whom the optimal clinical management is unclear. Such situations include those in which a guideline finds evidence insufficient to make a recommendation, a patient does not fit criteria mapped out in recommendations, or different organizations provide conflicting recommendations. Clinical experts provide opinions and comment on how they would approach the patient's care. Videos of the patient and conference, the slide presentation, and a CME/ MOC activity accompany each article. For more information, visit www.annals.org/GrandRounds. Series Editor, Annals: Deborah Cotton, MD, MPH Series Editor, BIDMC: Risa B. Burns, MD, MPH Series Assistant Editors: Eileen E. Reynolds, MD; Gerald W. Smetana, MD; Anjala Tess, MD, Howard Libman, MD This article is based on the Department of Medicine Grand Rounds conference held on 27 September 2018. Annals.org His physical examination, complete blood count, serum chemistry panel, liver function tests, and electrocardiogram were not revealing, and no imaging was performed. He was discharged home with a diagnosis of “acute abdominal pain, resolved.” In June 2018, Mr. R again developed abdominal symptoms; this time they were more severe and necessitated admission to a different local hospital. Evaluation revealed a patient in acute distress, with no fever, clear lungs, and a tender epigastrium. Laboratory studies showed a leukocyte count of 13.7 × 109/L, serum lipase level above 66.68 μkat/L, and total bilirubin concentration of 37.6 μmol/L (2.2 mg/dL). His blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, and serum calcium levels were normal. Abdominal ultrasonography of the right upper quadrant revealed cholelithiasis with some gallbladder wall thickening and trace pericholecystic fluid but no evidence of biliary dilation. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showed acute pancreatitis with a small amount of peripancreatic fluid but no signs of acute cholecystitis or cholelithiasis. Mr. R had bowel rest for 2 days, vigorous hydration with intravenous fluid, and symptomatic management with intravenous hydromorphone and ondansetron. His symptoms improved clinically, and the surgical team recommended cholecystectomy before discharge. However, Mr. R wanted to return to his own health system for care, and his surgery was scheduled there for 5 weeks after discharge. Nevertheless, 4 weeks after the patient was discharged, he was hospitalized in his own health system for another bout of acute pancreatitis after eating a fatty meal, and he underwent immediate cholecystectomy. Although he did well, he wonders whether waiting to have surgery caused permanent damage to his pancreas. © 2019 American College of Physicians 175 BEYOND THE GUIDELINES MR. R'S STORY It was in the fall of 2017 that I had my first attack of pain. I drove myself to the emergency room. They came back and said to me that everything checked out fine, and so there was nothing. I honestly thought maybe I got food poisoning. The next time it happened was at the beginning of June 2018. I started to feel pain in the center abdomen. Five minutes after it started, I broke into a sweat. It really wasn't a cold sweat anymore—just drenching, dripping sweat. We went back to the hospital emergency room. They said that a level of my liver was astronomically high and that I needed to be admitted for a gallstone attack. After about 24 to 36 hours, I felt fine. I had no more pain. I wasn't taking any more medication, and I felt like nothing ever happened. I was antsy to leave because I was falling behind at work and could come back for a scheduled surgery. When I asked to leave, the surgeon didn't mention consequences, but he did state that they typically do surgery during the initial stay for gallstone pancreatitis. The first hospital that I was admitted to was a chaotic experience. I didn't feel comfortable, so I wanted to get an appointment within my own hospital network. I ultimately left and scheduled my surgery for July 12 (5 weeks after my admission), but I ended up having another episode in that window. I didn't realize how serious acute pancreatitis can be. I thought it was just part of the gallstone attack and it's normal. Had I known I would be admitted or if a family member were to go to the emergency room now, I would make more of an effort to go to the hospital that is affiliated with the practice where our primary care doctors are. I would like to know if any damage was done to my pancreas. That's something that was never discussed with me. See the Patient Video (available at Annals.org) to view the patient telling his story. CONTEXT, EVIDENCE, AND GUIDELINES Acute pancreatitis is a common disorder of the pancreas and has several possible causes. Up to 50% of episodes are believed to be related to gallstones or alcohol use, the latter being an independent risk factor for gallstone disease (1). Other, less common causes include cancer, drug reactions, and hypertriglyceridemia. Inflammation occurs in both early and late phases, with the early phase typically lasting about 2 weeks and the late phase months to years. Acute pancreatitis is diagnosed on the basis of at least 2 of the following criteria: upper abdominal or back pain, increased serum lipase and amylase levels (>3 times the upper limit of normal), and evidence of pancreatic inflammation on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (2). Although most cases of acute pancreatitis are associated with only mild, local inflammation, up to 20% may cause a systemic inflammatory response resulting in multiorgan failure or death (2). Treatment strategies for acute pancreatitis have evolved over time. The American Gastroenterological Association Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee (3) published a guide176 Annals of Internal Medicine • Vol. 170 No. 3 • 5 February 2019 How Would You Treat This Patient With Gallstone Pancreatitis? line in 2018 to address the diagnosis and initial treatment of acute pancreatitis. On the basis of a systematic review of relevant studies of the first 72 hours to 7 days of illness, the guideline committee attempted to answer questions that had not been clearly addressed regarding the effect of treatment on the occurrence of persistent single- or multiple-organ failure, the development of pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis, and mortality (4). The committee used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach for collecting and analyzing evidence (3). Traditional teaching regarding the initial management of acute pancreatitis has advocated aggressive, unrestricted hydration. Four studies assessed whether goal-directed therapy would improve outcomes compared with unrestricted hydration and found no difference in the development of peripancreatic necrosis or in mortality (4). The degree, method, and timing of nutritional support also were examined, because recent studies have challenged the approach of “resting the pancreas” with “nothing by mouth” (NPO) during an acute episode. On the basis of data from several randomized controlled trials, the review found no difference in morbidity and mortality between patients whose acute pancreatitis was treated with an NPO approach and those who received early enteral feeding (4). Moreover, because no differences in critical clinical outcomes were found between patients randomly assigned to receive ERCP and those managed conservatively, the routine use of ERCP in managing acute pancreatitis has been discouraged (4). Lastly, the timing of cholecystectomy remains controversial, and this issue was addressed for mild pancreatitis only. One randomized controlled trial looked at surgery during the index admission versus delayed surgery at 1 month (4). Rates of readmission and other biliary complications were lower in the index admission group, although the optimal timing of surgery for patients with more severe pancreatitis remains unclear. CLINICAL QUESTIONS To structure a debate between our discussants, we mutually agreed on the following key questions to consider when applying this guideline to clinical practice in general and to Mr. R in particular. 1. What approach to fluid management and nutrition do you recommend? 2. What imaging is appropriate for guiding decision making for surgery? 3. When would you recommend that surgery be performed? DISCUSSION A Gastroenterologist's Viewpoint (Dr. Steven D. Freedman) Question 1: What approach to fluid management and nutrition do you recommend? Acute pancreatitis has an extensive range of presentations, and the severity affects both its course and optimal management (Table 1) (2, 3, 5, 6). Patients with Annals.org BEYOND THE GUIDELINES How Would You Treat This Patient With Gallstone Pancreatitis? mild pancreatitis generally improve in 2 to 3 days and can be managed safely on a general medical or surgical floor. Moderate pancreatitis is associated with evidence of transient organ failure lasting less than 48 hours. In contrast, severe pancreatitis involves permanent organ failure, including adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute kidney injury, or cardiovascular collapse. For example, a Bedside Index of Severity in Acute Pancreatitis score of 5 is associated with a 50% mortality rate (7). These patients are hemodynamically unstable and require treatment in an intensive care unit. My approach is to use severity scoring of acute pancreatitis to guide fluid requirements. A hematocrit greater than 0.44 may be an indicator of excess cytokine, including angiopoietin-2, which can lead to a vascular leak and third spacing (8). In patients like Mr. R who receive vigorous hydration, we must be careful not to “set it and forget it.” I recommend against starting at a set volume only to reassess the next day. I use the following formula to estimate the volume deficit (9): 冉 冊 measured hematocrit − baseline hematocrit baseline hematocrit ×1∕3 total body weight (kg) Thus, assuming a baseline hematocrit of 0.40, a 60-kg patient who has a hematocrit of 0.50 on admission has a 5-L deficit. Goal-directed bolus infusions should be given (10), and the hematocrit reassessed within 6 hours. I have found that the typical 120-mL/h intravenous continuous infusion exacerbates fluid deficits and increases risk for acute kidney injury over the initial 24 to 48 hours, especially given the large fluid requirements that frequently occur during this time frame. Conversely, overresuscitation also needs to be avoided because it can lead to abdominal compartment syndrome and ARDS (11, 12). I agree with the guideline: In someone with mild to moderate disease, I recommend goal-directed hydration over 24 to 48 hours that is targeted to clinical parameters, such as blood pressure or urine output, or biochemical parameters, such as hematocrit. As far as nutrition, the guideline suggests early oral feeding and, if not tolerated, progression to nasogastric or nasojejunal enteral feeding, with parenteral nutrition as a last resort. In this patient, I would follow the guideline and start goaldirected intravenous hydration, then wait 24 hours before any oral feeding to see how severe his disease is. If his symptoms improve, I would recommend oral feeding. If oral feeding is not tolerated, I would suggest resting for 48 hours and trying again, proceeding to enteral feeding only if oral feeding is not tolerated on the second try. Table 1. Assessment of Severity of Pancreatitis* Criteria Mild Moderate Severe Hematocrit BISAP score (5) APACHE II score Organ failure >0.44 <3 <8 None >0.44 >3 ≥8 Transient (<48 h) >0.44 >3 ≥8 Persistent (>48 h) APACHE II = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; BISAP = Bedside Index of Severity in Acute Pancreatitis. * Data from references 2, 3, 5, and 6. and to tell him or her how specific tests will affect management (Table 2) (13). Initially, in deciding whether the cause of the acute pancreatitis is biliary in origin, one needs to assess whether there are risk factors for gallstones, including older age, female sex, obesity, diabetes mellitus, estrogen use, pregnancy, Native American heritage, and rapid weight loss (14). Gallstone pancreatitis is usually associated with increased levels of liver enzymes, especially alkaline phosphatase, and direct bilirubin from transient bile duct obstruction, as in our patient. If these signs are present, abdominal ultrasonography of the right upper quadrant should be performed to assess for gallstones or sludge in the gallbladder. However, sludge is a frequent finding in 20% to 40% of patients, especially if they have not eaten and are dehydrated due to vomiting and third spacing of fluid. The sensitivity of ultrasonography in detecting gallstones is 84%, with 99% specificity (13). Importantly, I would consider what to do with these results. Do we want further testing, or do we assume a biliary origin regardless of the findings if there is no history of alcohol use? Establishing a reasonable pretest probability is essential for thoughtful decision making. There is generally no role for admission CT, unless you are looking for other causes of abdominal pain. Furthermore, it is not helpful to assess necrosis, because necrosis takes time to develop and, if found on admission, will probably not change management. Moreover, administration of intravenous contrast material in patients with hypovolemia may precipitate acute kidney injury. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography is potentially helpful for identifying choledocholithiaisis and for assessing other causes of acute pancreatitis, such as autoimmune disease. Studies have shown that 27% of patients presenting with gallstone pancreatitis will have a common bile duct stone on MRCP, with 94% sensitivity and 98% specificity (15). In patients with autoimmune pancreatitis, characteristic findings include rim enhancement, diffuse edema or segmental involvement, and pancreatic duct abnormalities (16). There is no role for ERCP, unless acute cholangitis from choledocholithiasis is present (17). Thus, for Mr. R, my only imaging study would be ultrasonography to confirm the presence of gallstones. Question 2: What imaging is appropriate for guiding decision making for surgery? Question 3: When should surgery be done? My approach is to obtain imaging only if needed. It is critical to include the patient in any of these decisions Results of a recent multicenter randomized controlled trial suggest that cholecystectomy on the index Annals.org Annals of Internal Medicine • Vol. 170 No. 3 • 5 February 2019 177 BEYOND THE GUIDELINES How Would You Treat This Patient With Gallstone Pancreatitis? Table 2. Utility of Imaging Studies in Assessment of Acute Pancreatitis Imaging Study Utility in Assessment Notes Ultrasonography CT MRCP Diagnoses cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, sludge, and bile duct dilatation Confirms pancreatitis; can assess other causes of abdominal pain Elucidates choledocholithiasis and can show nonbiliary causes, including autoimmune pancreatitis Defines and allows for removal of impacted stone with cholangitis 84% sensitivity and 99% specificity for detecting gallstones (13) Not helpful in assessing necrosis on admission – ERCP No role unless cholangitis is present CT = computed tomography; ERCP = endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; MRCP = magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. admission prevents further episodes of gallstone pancreatitis, assuming there are no overt complications of acute pancreatitis (18). This study randomly assigned 130 patients to have a cholecystectomy either before discharge or within 27 days after discharge. Three patients (2%) had recurrent pancreatitis after immediate surgery, versus 12 patients (9%) who underwent surgery later (risk ratio, 0.27 [95% CI, 0.08 to 0.92]; P = 0.03). (There was a 30% rate of endoscopic sphincterotomy in each group, but it is unclear how this affected outcomes.) However, older literature suggests that more than 80% of patients will pass the stone on the index admission (19, 20). Thus, if you do not see gallstones on ultrasonography, it is not clear that cholecystectomy would be of benefit. In addition, if you see only sludge, cholecystectomy is not clearly indicated. In deciding whether gallstones or sludge is the cause and whether to pursue a cholecystectomy, you should also consider whether the patient has known risk factors, as mentioned earlier. I agree with the guideline that surgery be performed on the index admission, but only when the gallbladder is clearly the culprit. In patients with pancreatitis complications or comorbid conditions, I favor waiting for stabilization. If pancreas divisum is present (Figure), I would not pursue surgery because the area of pancreas at risk is quite small. Further, most of the pancreas drains through the minor papilla, with no connection to the biliary tree (21). In addition, pancreatitis in these patients probably has genetic causes, including mutations in the CFTR, Figure. Pancreas divisum. Common bile duct Dorsal duct (of Santorini) Pancreas Duodenum Ventral duct (of Wirsung) Reproduced with permission from Chauhan A, Elsayes KM, Sagebiel T, Bhosale PR. The pancreas. In: Elsayes K, ed. Cross-sectional Imaging of the Abdomen and Pelvis. New York: Springer; 2015. 178 Annals of Internal Medicine • Vol. 170 No. 3 • 5 February 2019 SPINK1, and PRSS1 genes. For these reasons, I do not think cholecystectomy would be preventative in these cases and thus is not warranted (22, 23). To summarize, I would explain to the patient the rationale behind early surgery and recommend that it be performed by a general surgeon before discharge. If there were complications or if the diagnosis remained unclear, I would recommend waiting but perhaps involve a hepatobiliary surgeon in the final decision. If the patient did not feel comfortable with his current surgeon, I would contact his surgeon of choice and arrange an appointment, with a goal of performing cholecystectomy within 4 to 7 days. A Surgeon's Viewpoint (Dr. Tara Kent) Question 1: What approach to fluid management do you recommend? The guideline recommends goal-directed hydration with ongoing monitoring of volume requirements, particularly in the first 24 to 48 hours after presentation with acute pancreatitis (4). As Dr. Freedman outlines, it is critical to assess the severity of illness to guide expectations regarding the extent of fluid resuscitation. With respect to adequacy of resuscitation, the amount should always be guided by the patient's needs. It is important to give the necessary volume; however, it is equally important to be vigilant about changes in clinical status and the need to adjust resuscitation. Careful monitoring of urine output and other hemodynamic metrics is crucial. Mr. R had mild pancreatitis; therefore, less volume was needed to meet his needs. Overresuscitation can lead to other significant problems, including ARDS or abdominal compartment syndrome (11, 12), which complicate the management of pancreatitis and increase mortality. Abdominal compartment syndrome manifests with multiple organ system failure, as well as marked abdominal distention and increased bladder pressure, and requires emergent decompression. Although these complicating factors are unlikely in a patient with mild pancreatitis, it is important to understand the consequences of overresuscitation. Bladder pressure is an often-misunderstood metric for patients with severe pancreatitis. It is not relevant for a patient with stable pancreatitis who is awake, alert, and on a regular hospital ward—accurate measurement requires that the patient be supine, intubated, and paralyzed, so it should be done only in the intensive care unit (24). I agree with the guideline recommendations for nutrition in mild pancreatitis, including a trial of early oral feeding, usually within 1 to 2 days of presentation. Annals.org BEYOND THE GUIDELINES How Would You Treat This Patient With Gallstone Pancreatitis? Most patients with mild and improving pancreatitis will be able to resume a diet by this time (25). If intolerance to oral feeding persists, I suggest that cross-sectional imaging be considered to ensure that pancreatitis is not more severe than initially anticipated. Question 2: What imaging is appropriate for guiding decision making? All patients with pancreatitis should undergo abdominal ultrasonography of the right upper quadrant. Given that gallstones are the most common cause of pancreatitis, it is appropriate to investigate for the presence of cholelithiasis or choledocholithiasis in these patients. In a patient with no other obvious cause of pancreatitis who has ultrasonography-confirmed cholelithiasis and consistent laboratory study abnormalities, pancreatitis should be attributed to a biliary cause (26, 27). I agree that CT is generally not indicated at admission, except when alternative diagnoses are being considered, and is more useful after at least 72 hours, at the beginning of the late phase of disease. It is not useful to confirm the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis but can assess the degree of necrosis in patients who are not recovering. It can also identify potentially infected necrosis and the location and character of walled-off pancreatic necrosis or pseudocyst if an intervention is planned. Patients with severe pancreatitis undergo frequent radiologic studies. Delaying initial scanning and modifying the order to a single-phase study may help reduce the overall effective radiation dose (27, 28). If abdominal ultrasonography findings are negative but concern persists as to the cause of pancreatitis, MRCP can be obtained to evaluate for microlithiasis, anatomical abnormality, or mass lesion (29). In addition, it is useful for the identification of choledocholithiasis that is equivocal on the basis of ultrasonography and laboratory findings. Endoscopic ultrasonography may be useful but should be reserved for cases in which questions remain after noninterventional assessment. It is more accurate than MRCP in the diagnosis of microlithiasis. One important change from earlier recommendations is that ERCP is no longer recommended in patients with acute pancreatitis, unless there is clear biliary obstruction or cholangitis (17, 30). It is also worth considering in patients who cannot undergo cholecystectomy and for whom sphincterotomy is desired to “protect” against recurrent pancreatitis. Question 3: When should surgery be done? In cases of mild gallstone pancreatitis, the patient should undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy at the index presentation or admission, as recommended in the guideline (4). When surgery is performed at this time, there are fewer readmissions for recurrent pancreatitis or other gallstone-related disease, and there is no difference in rates of mortality or conversion to open surgery (31). If pancreatitis is moderate or severe and associated with peripancreatic collections or necrosis, surgery may be delayed until the patient's overall status is imAnnals.org proved, systemic findings of pancreatitis have subsided, and fluid collections and necrosis have stabilized (30). In this group of patients, interval cholecystectomy is associated with decreased morbidity and mortality (30, 32). Patients with biliary pancreatitis who have undergone ERCP or sphincterotomy should still have laparoscopic cholecystectomy, because the sphincterotomy protects against pancreatitis and cholangitis but not against cholecystitis. If surgery is delayed, as was the case with Mr. R, there is a risk for recurrent pancreatitis as well as a risk for simply losing the patient to follow-up. There may be logistical considerations in terms of undertaking cholecystectomy at the index admission. These may include operating room or surgeon availability, patient preferences related to professional or life events, and patient comorbidity optimization. In general, surgical risks and the risk for surgical complications must be weighed against the risk for recurrent, or even more severe, pancreatitis or sequelae if surgery does not occur. To reduce the risk of delay, if pancreatitis is mild and the patient is an appropriate surgical candidate, surgery should occur before discharge. For those who decline surgical intervention at that time, it is important for practitioners to ensure that these patients truly understand the risks of this decision. Patient and family education is critical, and a clear follow-up plan must be established. Even when cholelithiasis, microlithiasis, or sludge is identified, questions may remain about the cause. For example, a patient may present with alcohol abuse as well as cholelithiasis. Even if it is not certain that the stones are the cause of the acute pancreatitis, if confirmed the patient should be considered for cholecystectomy. Similarly, if there is autoimmune pancreatitis but also cholelithiasis, the patient should be treated for autoimmune pancreatitis and also be considered for cholecystectomy. SUMMARY Mr. R presented with biliary colic followed by an episode of mild gallstone pancreatitis. His symptoms improved quickly, but his pancreatitis recurred 4 weeks later, a week before a scheduled cholecystectomy. He was readmitted, and cholecystectomy was performed. Both discussants agree that his initial presentation represented mild pancreatitis, given the absence of multiorgan failure and his rapid improvement within 24 to 48 hours. Both also agree with the guideline that goaldirected fluid resuscitation is the best approach to avoid complications of under- and over-resuscitation. Dr. Freedman would wait 24 hours to determine the disease trajectory before starting oral nutrition; if oral nutrition is not tolerated, he would try it again after another 24 hours. Dr. Kent would start oral nutrition in 24 to 48 hours; however, if the patient does not tolerate it, she would be concerned about complications of pancreatitis. She would pursue cross-sectional imaging of the pancreas before an enteral rechallenge. Both discussants agree that routine imaging with CT or MRCP is Annals of Internal Medicine • Vol. 170 No. 3 • 5 February 2019 179 BEYOND THE GUIDELINES AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES Dr. Tess is Associate Chair for Education in the Department of Medicine at BIDMC, and Program Director for the Master Program in Healthcare Quality and Safety and Associate Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Freedman is Director of The Pancreas Center at BIDMC, and Chief of the Division of Translational Research and Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Kent is Vice Chair for Education, Program Director, General Surgery Residency Program at BIDMC, and Associate Professor of Surgery at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Libman is a clinician educator in the Division of General Medicine, BIDMC, and Professor of Medicine Emeritus at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts. not necessary, unless another cause of the pancreatitis is suspected or there is potential for retained stones or cholangitis. Dr. Kent advocates abdominal ultrasonography in all patients because of the high likelihood of gallstone disease. Dr. Freedman recommends the same but questions whether it ultimately changes management. The guideline states that cholecystectomy should be performed on the index admission. Dr. Freedman agrees, but only if gallstones are clearly the cause of the pancreatitis, no other causes are evident, and no complications exist. Dr. Kent also agrees with the guideline but would pursue surgery even with evidence of microlithiasis or sludge. The discussants concur that they would have counseled Mr. R, who wanted to have the operation in his own medical system, regarding the risks of delaying surgery. They would have also more actively managed the handoff to his outpatient physicians to expedite scheduling of cholecystectomy within 1 week after discharge. A transcript of the audience question-and-answer period is available in the Appendix (available at Annals .org). To view the entire conference video, including the question-and-answer session, go to Annals.org. From Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts (A.T., S.D.F., T.K., H.L.). Acknowledgment: The authors thank the patient for sharing his story. Grant Support: Beyond the Guidelines receives no external support. Disclosures: Authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest. Forms can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje /ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M18-3536. 180 Annals of Internal Medicine • Vol. 170 No. 3 • 5 February 2019 How Would You Treat This Patient With Gallstone Pancreatitis? Corresponding Author: Anjala Tess, MD, Division of General Medicine and Primary Care, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, E/Yamins 102, 330 Brookline Avenue, Boston, MA 02215; e-mail, atess@bidmc.harvard.edu. Current author addresses are available at Annals.org. References 1. Krishna SG, Kamboj AK, Hart PA, Hinton A, Conwell DL. The changing epidemiology of acute pancreatitis hospitalizations: a decade of trends and the impact of chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2017;46:482-488. [PMID: 28196021] doi:10.1097/MPA .0000000000000783 2. Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, et al; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:10211. [PMID: 23100216] doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779 3. Crockett SD, Wani S, Gardner TB, Falck-Ytter Y, Barkun AN; American Gastroenterological Association Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on initial management of acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1096-1101. [PMID: 29409760] doi:10.1053/j.gastro .2018.01.032 4. Vege SS, DiMagno MJ, Forsmark CE, Martel M, Barkun AN. Initial medical treatment of acute pancreatitis: American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review. Gastroenterology. 2018; 154:1103-1139. [PMID: 29421596] doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01 .031 5. Wu BU, Johannes RS, Sun X, Tabak Y, Conwell DL, Banks PA. The early prediction of mortality in acute pancreatitis: a large populationbased study. Gut. 2008;57:1698-703. [PMID: 18519429] doi:10.1136 /gut.2008.152702 6. Banks PA, Freeman ML; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2379-400. [PMID: 17032204] 7. Singh VK, Wu BU, Bollen TL, Repas K, Maurer R, Johannes RS, et al. A prospective evaluation of the bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis score in assessing mortality and intermediate markers of severity in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009; 104:966-71. [PMID: 19293787] doi:10.1038/ajg.2009.28 8. Brown A, Orav J, Banks PA. Hemoconcentration is an early marker for organ failure and necrotizing pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2000;20: 367-72. [PMID: 10824690] 9. Freedman SD, Uppot RN, Mino-Kenudson M. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 26-2009. A 34-year-old man with cystic fibrosis with abdominal pain and distention. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:807-16. [PMID: 19692693] doi:10.1056/NEJMcpc 0902225 10. Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, et al; Early Goal-Directed Therapy Collaborative Group. Early goaldirected therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368-77. [PMID: 11794169] 11. de-Madaria E, Soler-Sala G, Sánchez-Payá J, Lopez-Font I, Martı́nez J, Gómez-Escolar L, et al. Influence of fluid therapy on the prognosis of acute pancreatitis: a prospective cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1843-50. [PMID: 21876561] doi:10.1038/ajg.2011 .236 12. De Waele JJ, Leppäniemi AK. Intra-abdominal hypertension in acute pancreatitis. World J Surg. 2009;33:1128-33. [PMID: 19350318] doi:10.1007/s00268-009-9994-5 13. Shea JA, Berlin JA, Escarce JJ, Clarke JR, Kinosian BP, Cabana MD, et al. Revised estimates of diagnostic test sensitivity and specificity in suspected biliary tract disease. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154: 2573-81. [PMID: 7979854] Annals.org How Would You Treat This Patient With Gallstone Pancreatitis? 14. Stinton LM, Shaffer EA. Epidemiology of gallbladder disease: cholelithiasis and cancer. Gut Liver. 2012;6:172-87. [PMID: 22570746] doi: 10.5009/gnl.2012.6.2.172 15. Makary MA, Duncan MD, Harmon JW, Freeswick PD, Bender JS, Bohlman M, et al. The role of magnetic resonance cholangiography in the management of patients with gallstone pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2005;241:119-24. [PMID: 15621999] 16. Chari ST, Takahashi N, Levy MJ, Smyrk TC, Clain JE, Pearson RK, et al. A diagnostic strategy to distinguish autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1097103. [PMID: 19410017] doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2009.04.020 17. Tse F, Yuan Y. Early routine endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography strategy versus early conservative management strategy in acute gallstone pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD009779. [PMID: 22592743] doi:10.1002/14651858 .CD009779.pub2 18. da Costa DW, Bouwense SA, Schepers NJ, Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC, van Brunschot S, et al; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Same-admission versus interval cholecystectomy for mild gallstone pancreatitis (PONCHO): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:1261-1268. [PMID: 26460661] doi:10 .1016/S0140-6736(15)00274-3 19. Tranter SE, Thompson MH. Spontaneous passage of bile duct stones: frequency of occurrence and relation to clinical presentation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2003;85:174-7. [PMID: 12831489] 20. Stone HH, Fabian TC, Dunlop WE. Gallstone pancreatitis: biliary tract pathology in relation to time of operation. Ann Surg. 1981;194: 305-12. [PMID: 6168240] 21. Health Life Media. Pancreas divisum. Accessed at http://health lifemedia.com/healthy/pancreas-divisum/ on 17 September 2018. 22. Gelrud A, Sheth S, Banerjee S, Weed D, Shea J, Chuttani R, et al. Analysis of cystic fibrosis gener product (CFTR) function in patients with pancreas divisum and recurrent acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1557-62. [PMID: 15307877] 23. Schwarzenberg SJ, Bellin M, Husain SZ, Ahuja M, Barth B, Davis H, et al. Pediatric chronic pancreatitis is associated with genetic risk factors and substantial disease burden. J Pediatr. 2015;166:890896.e1. [PMID: 25556020] doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.11.019 24. Department of Surgical Education, Orlando Regional Medical Center. Intra-abdominal pressure monitoring. Accessed at www Annals.org BEYOND THE GUIDELINES .surgicalcriticalcare.net/Guidelines/IAP%202015.pdf on 17 September 2018 25. Vaughn VM, Shuster D, Rogers MAM, Mann J, Conte ML, Saint S, et al. Early versus delayed feeding in patients with acute pancreatitis: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:883-892. [PMID: 28505667] doi:10.7326/M16-2533 26. Avanesov M, Weinrich JM, Kraus T, Derlin T, Adam G, Yamamura J, et al. MDCT of acute pancreatitis: intraindividual comparison of single-phase versus dual-phase MDCT for initial assessment of acute pancreatitis using different CT scoring systems. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85:2014-2022. [PMID: 27776654] doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.09 .013 27. Brand M, Götz A, Zeman F, Behrens G, Leitzmann M, Brünnler T, et al. Acute necrotizing pancreatitis: laboratory, clinical, and imaging findings as predictors of patient outcome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:1215-31. [PMID: 24848818] doi:10.2214/AJR.13.10936 28. Reynolds PT, Brady EK, Chawla S. The utility of early crosssectional imaging to evaluate suspected acute mild pancreatitis. Ann Gastroenterol. 2018;31:628-632. [PMID: 30174401] doi:10 .20524/aog.2018.0291 29. Park JY, Jeon TJ, Ha TH, Hwang JT, Sinn DH, Oh TH, et al. Bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis: comparison with other scoring systems in predicting severity and organ failure. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2013;12:645-50. [PMID: 24322751] 30. Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013;13:e1-15. [PMID: 24054878] doi:10.1016/j .pan.2013.07.063 31. Aboulian A, Chan T, Yaghoubian A, Kaji AH, Putnam B, Neville A, et al. Early cholecystectomy safely decreases hospital stay in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis: a randomized prospective study. Ann Surg. 2010;251:615-9. [PMID: 20101174] doi:10.1097/SLA .0b013e3181c38f1f 32. Nealon WH, Bawduniak J, Walser EM. Appropriate timing of cholecystectomy in patients who present with moderate to severe gallstone-associated acute pancreatitis with peripancreatic fluid collections. Ann Surg. 2004;239:741-9; discussion 749-51. [PMID: 15166953] Annals of Internal Medicine • Vol. 170 No. 3 • 5 February 2019 181 Current Author Addresses: Drs. Tess, Freedman, Kent, and Libman: Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 330 Brookline Avenue, Boston, MA 02215. APPENDIX: COMMENTS AND QUESTIONS Dr. Libman: I think Anjala has the first question, which I believe was posed by our patient. Dr. Tess: The patient unfortunately could not make it today, but his concern is that he ended up having what sounds like 2 episodes of mild pancreatitis. He wonders if he caused permanent damage to his pancreas because of the delay in having surgery. Dr. Kent: He probably had biliary colic in the fall presentation and should have had an evaluation and a laparoscopic cholecystectomy at that time. We do see patients with damage to the pancreas as a result of pancreatitis, with respect to both endocrine and exocrine insufficiency, and typically more in severe pancreatitis. Most likely, this patient will be just fine. Dr. Freedman: In a patient with no prior pancreatic disease and no underlying risk factors for chronic pancreatitis, most likely the pancreas will regenerate and there will be no sequelae as a result of these episodes. Dr. Eileen Reynolds: Thank you both for terrific presentations. I love that this patient did not want anything done to him until he talked to his primary care doctor. Maybe it would have changed things had somebody from the hospital contacted the primary care doctor and said, “It really matters that we do this; can you talk to the patient?” So, my plea is to engage the primary care doctor in the clinical course. Now, I have a question. For many patients these days, there is a financial implication to staying within their hospital network. For this and other reasons, I am wondering whether it was important enough for this patient to have early surgery that we should have transferred him to his home network rather than discharging him. Dr. Freedman: Very important and valid points. I would have assumed that right after the first admission to the outside hospital for pancreatitis, the staff there would have reached out to the primary care doctor and discussed the situation. I think as far as the financial implications, it is absolutely a valid point and should be discussed with the patient as well. I think no matter what, if a patient is going to go through something invasive, he should be comfortable with the physician who is doing the procedure and the institution where it is being performed. Dr. Kent: I think you raise a really good point, and we should definitely be engaging the primary care physician in discussion. In terms of transferring patients back to their home facility for surgery, in my experience, that rarely happens, for practical reasons. Dr. Mark Zeidel: Has the timing of surgery changed now that we do it laparoscopically as opposed to an open procedure? There used to be, I think, a lot of Annals.org concern about doing an open procedure in someone with active pancreatitis. Is there really a difference? I know sometimes we have to convert from one procedure to the other. Dr. Kent: In patients with mild pancreatitis, the gallbladder itself is typically not severely affected. Doing a laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be more challenging in a patient with moderate or severe pancreatitis if there are more phlegmons, or peripancreatic fluid extends up toward the gallbladder. However, I do not believe that we can attribute the change in recommended timing to the fact that laparoscopic cholecystectomy is now the standard of care. Dr. Elizabeth Kass: If the patient, as he did in this case, leaves the hospital before having surgery performed, how important is specific dietary advice? Dr. Freedman: That is a great question. We generally tell patients to be on a lower-fat diet, because fat is the ultimate stress test on your pancreas and potentially stimulates gallbladder contraction through cholecystokinin and other signals. I am not sure we have scientific data to back that up, but it is not unusual for patients to say, “Oh, I had a fatty meal, and now I'm either having biliary colic or coming in with pancreatitis.” Hydration is also important to emphasize. If you get dehydrated, your gastrointestinal secretions will thicken, which may predispose to recurrent pancreatitis. Dr. Kent: I agree. We advise patients to have a lowfat diet and to stay well hydrated. We also make sure to set up a postdischarge phone call with our nurses to check in with patients on their state of hydration and eating habits. Dr. Tess: Interestingly, this patient was following a low-fat diet, but it was the July 4th weekend and he stopped and got ice cream. Right after that, he was readmitted with the second bout of pancreatitis. Dr. Jessica Berwick: I was wondering how you counsel patients about the risk for recurrent pancreatitis from remnant duct stones. I know we talked about the 2% risk for recurrence, but I did not know how much of that was from stones in the remnant duct versus other causes of pancreatitis. Dr. Kent: Nowadays, it is less likely that they will have an ERCP than in the past. Before we do their laparoscopic cholecystectomy, I counsel patients that there may have been stones that escaped from the gallbladder into the ducts before the surgery and that they can cause a similar presentation of symptoms, particularly within the first 2 years after surgery. Dr. Michael Apstein: Both of you alluded to the role of defining the etiology clearly, and I think Tara referred to biliary sludge. I know from studies 20 years ago that elimination of biliary sludge reduced the risk for recurrent pancreatitis. Do you think biliary sludge is a player in this process? Do you think that patients who have sludge and no stones should have a cholecystectomy? Annals of Internal Medicine • Vol. 170 No. 3 • 5 February 2019 Dr. Freedman: The problem with sludge is that it is very common, and it is difficult to determine in which patients it is truly the cause. If you look at everyone coming in with acute pancreatitis, I think at least 40% will have sludge, so I generally follow up with the patient. It is important to consider other causes in this setting, such as autoimmune or medication-induced pancreatitis. Dr. Kent: I think we differ a bit on this point. I believe that there is a decrease in subsequent episodes of pancreatitis in patients with sludge who undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy. I would consider surgery in these patients because, in addition to the pancreatitis, we know that the cholecystitis impact is still there, even if they passed the stones and sludge that caused the pancreatitis. Dr. Daniele Olveczky: As nocturnists, we often admit patients for ERCP before they undergo cholecystectomy Annals of Internal Medicine • Vol. 170 No. 3 • 5 February 2019 and wonder how necessary this is, because for many patients, it does not seem to affect their management. Dr. Freedman: I think if there is clear evidence of ongoing bile duct obstruction from an impacted stone or another cause, then ERCP is indicated, especially in the setting of cholangitis. Otherwise, I think it needs to be a thoughtful decision making and not just a kneejerk response of “Yes, you should get this invasive test.” We have a pancreatitis service that coordinates with surgeons and the ERCP team, and I think that we can guide management. Dr. Kent: There are still many reasons why patients should have ERCP on admission, whether it is for pancreatitis or, more commonly, for choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, or suspicion of a mass. Dr. Tess: Thank you to our discussants and to Dr. Libman for moderating this session. Annals.org