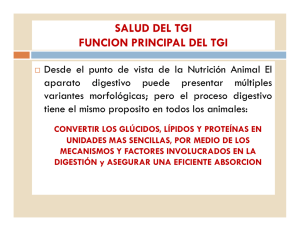

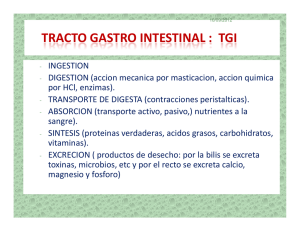

MICROBIOTA GASTROINTESTINAL Jesús Abraham Armenta Gonzalez what is the intestinal microbiota? The human digestive tract is home to a large population (100 billion), mainly bacteria, but also archaea, fungi, viruses and eukaryotes (or protozoa), which have been adapted to life on mucosal surfaces or in the lumen of the intestine for millennia. factors on which we can act: • feeding modes (breast milk, infant formulas and introduction of solid foods); • drugs (antibiotics, antacids, antidiabetics, etc.); • eating habits and ways of cooking; • our environment and our way of life (rural vs. urban environment; physical activity); • weight gain. factors on which we cannot act directly: • a genetic; • the anatomical component of the intestinal tract (e.g., the microbial diversity of the intestine is greater than that of the small intestine); • gestational age (preterm versus term delivery); • mode of birth (vaginal versus cesarean delivery); • age. functions of the intestinal microbiota Defense: Defends us against harmful microorganisms. Teaches the immune system to distinguish between friend and foe. It degrades toxins. Nutrition: Allows digestion of certain foods (such as dietary fibers) that humans cannot digest. When the intestinal microbiota breaks down dietary fibers, it produces important molecules (short-chain fatty acids, for example) whose benefits go beyond the intestine. It facilitates the absorption of minerals (magnesium, calcium and iron). It synthesizes certain essential vitamins (vitamin K and folate [B9]) and amino acids (i.e., the foods that make up proteins). Behavior: May influence mood and behavior. CONCLUSION The human gut harbors a diverse community of commensal bacteria, in a symbiotic relationship with the host, thereby permanently influencing its physiology. There is clear evidence that bacteria-host interactions in the gut mucosa play a very important role in the development and regulation of the immune system. If this interaction is not adequate, the homeostasis between the environmental antigenic load and the individual's response may fail. This can result in the development of pathologies of immune dysregulation against one's own antigenic structures (autoimmunity), including one's own microflora (inflammatory bowel disease), or antigenic structures from the environment (atopy).