Producción de la identidad colectiva en una comunidad andina

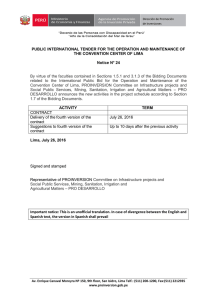

Anuncio