A. James Gregor, Mussolini's Intellectuals - Fascist Social and Political Thought

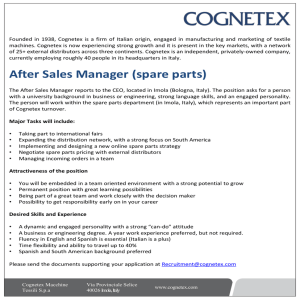

Anuncio