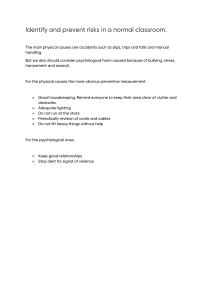

AGGRESSIVE BEHAVIOR Volume 40, pages 56–68 (2014) Moral Disengagement Among Children and Youth: A Meta‐Analytic Review of Links to Aggressive Behavior Gianluca Gini1*, Tiziana Pozzoli1, and Shelley Hymel2 1 2 Department of Developmental and Social Psychology, University of Padua, Padova, Italy Faculty of Education, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. A growing body of research has demonstrated consistent links between Bandura’s theory of moral disengagement and aggressive behavior in adults. The present meta‐analysis was conducted to summarize the existing literature on the relation between moral disengagement and different types of aggressive behavior among school‐age children and adolescents. Twenty‐seven independent samples with a total of 17,776 participants (aged 8–18 years) were included in the meta‐analysis. Results indicated a positive overall effect (r ¼.28, 95% CI [.23, .32]), supporting the hypothesis that moral disengagement is a significant correlate of aggressive behavior among children and youth. Analyses of a priori moderators revealed that effect sizes were larger for adolescents as compared to children, for studies that used a revised version of the original Bandura scale, and for studies with shared method variance. Effect sizes did not vary as a function of type of aggressive behavior, gender, or publication status. Results are discussed within the extant literature on moral disengagement and future directions are proposed. Aggr. Behav. 40:56–68, 2014. © 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Keywords: aggression; bullying; cyberbullying; moral disengagement; meta‐analysis INTRODUCTION Aggressive behavior toward peers during childhood and adolescence has been studied for decades (Dodge, Coie, & Lynam, 2006) and has been shown to be a significant correlate, both concurrently and longitudinally, of poor health and maladjustment in both perpetrators and victims (e.g., Card, Stucky, Sawalani, & Little, 2008; Gini & Pozzoli, 2009, 2013; Ttofi, Farrington, Losel, & Loeber, 2011). Although the majority of aggressive children display temporary or desisting aggressive behavior, about 10% of the general population are persistently aggressive over the years and can follow a deviant “career” path (Pepler, Jiang, Craig, & Connolly, 2008). Personal correlates and risk factors for youth aggressive behavior include positive attitudes toward (Carney & Merrell, 2001; Rigby & Slee, 1993) and high self‐efficacy for (Andreou & Metallidou, 2004) the use of aggression, low empathy (e.g., Gini, Albiero, Benelli, & Altoè, 2007a; Jolliffe & Farrington, 2011), and high masculinity (Gini & Pozzoli, 2006). Individual differences in aggression have also been attributed to biases in morality, with aggressive behavior linked to distorted moral reasoning that helps to minimize guilt (Arsenio & Lemerise, 2004; Caravita, Gini, & Pozzoli, 2012; Hymel, Schonert‐Reichl, Bonanno, Vaillancourt, & Rocke Henderson, 2010; Malti, Gasser, & Gutzwiller‐ Helfenfinger, 2010; Menesini, Nocentini, & Camodeca, 2013; Tisak, Tisak, & Goldstein, 2006). The present study focused on one particular type of moral reasoning, moral disengagement (henceforth MD), as described in Bandura’s social cognitive theory of moral agency (1986, 1990). Specifically, this study reports on the first meta‐analytic synthesis of developmental research on the relation between MD and aggressive behavior in school‐age children and youth. We also explored the factors that might moderate the effect of MD on aggression, including the type of aggressive behavior, participant characteristics (age, gender), and methodological features of the studies conducted to date. Social Cognitive Theory of Moral Behavior Bandura (1986, 1990, 1991) focused on moral reasoning and its relation to social behavior in an attempt to Correspondence to: Gianluca Gini, Department of Developmental and Social Psychology, University of Padua, via Venezia 8, Padova 35131, Italy. E‐mail: gianluca.gini@unipd.it Received 10 November 2012; Accepted 24 July 2013 DOI: 10.1002/ab.21502 Published online 13 September 2013 in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com). © 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Moral Disengagement and Aggressive Behavior explain how “good” people can behave “badly”. With age, children develop standards of right and wrong that serve as guides for their conduct. Through this self‐ regulatory process, individuals usually act in ways that give them satisfaction and a sense of self‐worth, and tend to avoid behaviors that violate their moral standards in order to prevent or minimize self‐condemnation. However, Bandura (2002) argued that the self‐regulation of behavior involves more than just moral reasoning, and that moral reasoning is linked to moral behavior through a series of self‐regulatory mechanisms through which moral agency is exercised. Moreover, the development of self‐regulation does not create an invariant control system within a person, and there are many psychological and social processes by which self‐sanctions can be disengaged. Selective activation and disengagement of internal control permit different types of conduct— sometimes very negative—with the same moral standards. Specifically, Bandura described eight mechanisms, clustered into four broad categories through which moral control can be disengaged (see Hymel et al., 2010, for a more detailed discussion). The first, cognitive restructuring, operates by framing the behavior itself in a positive light, by (i) portraying immoral conduct as warranted (moral justification); (ii) contrasting a negative act with worse conduct (advantageous comparison); or (iii) using language which palliates the condemned act, thus diminishing its severity (euphemistic labeling). The second set of disengagement strategies operates by obscuring or minimizing one’s agentive role in the harm caused (displacement or diffusion of responsibility). The third set of strategies operates by minimizing, disregarding or distorting the consequences of one’s action, allowing individuals to distance themselves from the harm caused or to emphasize positive rather than negative outcomes (minimizing or misconstruing consequences). Finally, negative feelings can be avoided by stripping the recipients of detrimental acts of human qualities (dehumanization) or considering aggression as provoked by the victim (attribution of blame). These mechanisms can lead to aggressive behaviors through a process of MD, that is a partial gap between the “abstract” personal idea of moral behavior and the individual’s real life behavior. In this way, the individual protects him/ herself from negative feelings, such as guilt or shame, that usually follow immoral conduct (Bandura, 1991). Measures of Moral Disengagement Bandura et al. were the first to develop self‐report scales to measure proneness to MD (Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, & Pastorelli, 1996; Caprara, Pastorelli, & Bandura, 1995). A short version (14 items) of his moral disengagement scale has been adapted for use with elementary school children, a 24‐item version has been 57 developed for adolescents, and a longer scale consisting of 32 items is used with adults (Caprara et al., 1995). The scale has also been adapted to specific populations (i.e., American minority youth; Pelton, Gound, Forehand, & Brody, 2004) and it is sometimes used in revised versions including subsets of the original items (e.g., Ando, Asakura, & Simons‐Morton, 2005; Barchia & Bussey, 2011). The scale has shown good reliability (a ¼ .81; Bandura et al., 1996), and is by far the most commonly used measure of MD across countries. A few studies have used different scales of MD. Hymel, Rocke‐Henderson, and Bonanno (2005) also utilized self‐reports to assess MD in children and youth, although their survey focused specifically on MD regarding peer bullying. The original 18 items of the scale were identified “post hoc” from a larger survey about bullying as reflecting the four broad categories of MD outlined by Bandura (2002). However, factor analytic results failed to distinguish the four different types of MD and instead yielded a single, 13‐item scale tapping overall MD with regard to bullying (a ¼ .81). Nevertheless, this measure has been adopted by other researchers (Almeida, Correia, Marinho, & Garcia, 2012; Vaillancourt et al., 2006). Although the Bandura and Hymel et al. scales show a significant degree of conceptual overlap, a recent study considering a subset of items from each scale indicated a moderate association between the two (r ¼ .51; Ribeaud & Eisner, 2010), with the Bandura scale tapping a broader range of MD beliefs and the Hymel et al. scale tapping a more restricted set of MD beliefs about peer bullying.1 Moral Disengagement and Different Types of Aggressive Behavior Starting from early age, individuals who morally disengage may perceive some types of antisocial behavior as reasonable or justified, at least under some circumstances, even if they have internalized moral rules that prohibit such behavior. Indeed, research has shown that children and youth who endorse these mechanisms are more likely to engage in both general aggression (e.g., Bandura et al., 1996; Caprara et al., 1995) and peer bullying (e.g., Gini, 2006; Hymel et al., 2005). Importantly, the link between MD and aggressive behavior remains significant even after other predictors of such behavior, such as aggression efficacy, rule perception, or parenting, are controlled (e.g., Barchia & Bussey, 2011; Caravita & Gini, 2010; Pelton et al., 2004). Interestingly, 1 Menesini et al. (2003) have investigated MD by assessing children’s attributions of morally engaged emotions (guilt, shame) versus disengaged emotions (pride, indifference) in response to hypothetical moral transgressions. In this meta‐analysis we did not include that study because its methodology differs importantly from those considered here. Aggr. Behav. 58 Gini et al. MD has been shown to be a significant correlate of these behaviors in juvenile delinquents samples (Hodgdon, 2010; Kiriakidis, 2008; Shulman, Cauffmann, Piquero, & Fagan, 2011), representing extremely violent individuals, as well as community samples, thus confirming that MD mechanisms operate within the “normal” range of psychological functioning (Bandura, 1986). Of recent interest is the degree to which MD is associated with cyberbullying, defined as aggressive behavior perpetrated via information and communication technologies, such as the Internet and mobile phones (Smith et al., 2008). Several authors have suggested that MD might be less evident with cyberbullying, albeit for different reasons. Pornari and Wood (2010), for example, suggest that online aggression may not demand the same level of rationalization and justification as traditional aggression because youngsters might consider cyberbullying as less serious than traditional forms of aggression and “the anonymity, the distance from the victim, and the consequences of the harmful act do not cause so many negative feelings (e.g., guilt, shame, self‐condemnation), and reduce the chance of empathizing with the victim” (p. 89). Others (e.g., Bauman, 2010; Perren & Sticca, 2011) argue that the inability to observe the immediate reaction of the victim may allow the aggressor to minimize the impact of the negative behavior; this would make MD less necessary. Indeed, the “online disinhibition effect” (Suler, 2004), which refers to a loosening of social/moral restrictions and inhibitions during online interaction that would otherwise be present in face‐to‐face interaction, itself can represent a variation of MD, allowing the individuals to behave in ways that are contrary to their moral code. Drawing upon this literature, our first aim was to evaluate the strength of the association between MD and any form of peer‐directed aggressive behavior among school‐age children and youth. Of additional interest was whether the magnitude of this effect varied as a function of the behavior considered (e.g., aggression vs. bullying vs. cyberbullying). Testing Potential Moderators Three categories of potential moderators were hypothesized to influence the relationship between MD and various forms of aggressive behavior. First considered are participant characteristics, specifically age and sex. Previous longitudinal research by Paciello, Fida, Tramontano, Lupinetti, and Caprara (2008) examined stability and change in MD and its relation to aggressive behavior among 366 Italian adolescents, followed at four time points from 14 to 20 years. Although generally MD appeared to decline with age, especially between ages 14 and 16, four distinct trajectories were identified: (i) non‐ disengaged adolescents (37.9% of the sample) who initially showed low levels of MD followed by a Aggr. Behav. significant decline, (ii) a normative group (44.5%) with initially moderate levels that later declined, (iii) a “later desistent” group (6.9%) that started with initially high‐ medium levels followed by a significant increase from ages 14 to 16 and an even steeper decline from ages 16 to 20, and (iv) a “chronic” group (10.7%) that maintained constant medium‐high levels of MD. Importantly, youth who maintained high levels of MD were more likely to engage in aggressive acts in later adolescence. At least one study has reported age differences in mean levels of MD favoring older students (e.g., Barchia & Bussey, 2011), whereas others reported no significant age differences (e.g., Bandura et al., 1996; Pornari & Wood, 2010). However, these studies did not assess directly whether age‐groups differed in the link between MD and aggressive behavior. This meta‐analysis tested whether the relation between MD and aggression varied as a function of age, comparing studies of children versus adolescents. Consistent with Bandura’s idea that moral disengagement develops over time as a result from behaving in contrast to internal moral values, it was expected that the relation between MD and aggression would be stronger in adolescence as compared to childhood. Regarding sex differences, higher levels of self‐ exonerating mechanisms have consistently been found in male as compared to female samples from different cultural contexts, even after controlling for other demographic variables, such as ethnicity or socio‐ economic status (Bandura et al., 1996; Obermann, 2011; Yadava, Sharma, & Gandhi, 2001). Less clear is whether the magnitude of the relation between MD and aggression varies across boys and girls. Some authors have suggested stronger links for boys (Bussman, 2007; Paciello et al., 2008), others report the reverse (Yadava et al., 2001), and still others find no moderating effect of gender (Gini, 2006; Obermann, 2011). Accordingly, the present meta‐analysis tested directly whether sex moderated the link between MD and aggressive behavior. Discrepancies in findings across studies as a function of methodological differences were also considered. First, because different scales to measure MD exist, we tested whether effect sizes varied as a function of the type of instrument, by comparing studies that used the original scale devised by Bandura, studies that used a revised shortened version of that scale, and studies that employed other scales. Second, although MD is always assessed through self‐reports, studies differ in their assessments of children’s aggressive behavior, with self, peers, and adults (teachers, parents) used as sources of information. As demonstrated in a previous meta‐analysis by Hawker and Boulton (2000) on the relations between peer victimization and psychosocial adjustment, use of the same informant for both constructs can inflate the Moral Disengagement and Aggressive Behavior magnitude of the measured effects due to shared method variance. Accordingly, this meta‐analysis tested whether this feature accounted for differences in effect sizes across studies. Finally, publication bias is a threat to any meta‐analytic review, with concern that unpublished studies are more likely to have smaller or non‐significant results and less likely to be included in a meta‐analysis than published studies, yielding estimated effect sizes larger than those that actually exist. To reduce publication bias, efforts were made to include as many unpublished studies as possible (e.g., dissertations, conference papers). To check whether a significant difference existed between published and unpublished studies in the reported effect sizes, we also tested for the moderating effect of publication status. METHODS Literature Search Multiple methods were used to identify potentially eligible studies. First, computer literature searches from the year each database started until March 2012 were conducted using PsychInfo, Educational Research Information Center, Scopus and Google Scholar with “moral disengagement,” “aggressive behavior,” “aggression,” “bullying,” “school violence,” “antisocial behavior” used as keywords. Second, recent review articles and book chapters on aggressive behavior, bullying, or morality in children were reviewed for relevant citations. Third, reference sections of the collected articles were searched for relevant earlier references (i.e., “backward search” procedure). Finally, authors were contacted directly to obtain other relevant studies. With unpublished studies (conference papers, dissertations), principal investigators were contacted to ask for ad hoc analysis (if no response was received, a second e‐mail was sent 2–3 months after the first). A total of 70 potentially relevant journal articles, chapters, conference and dissertation abstracts were reviewed. Inclusion Criteria The most basic requirement for inclusion in the present meta‐analysis was consideration of measures of Bandura’s MD mechanisms and any form of aggressive behavior, or bullying, or cyberaggression/cyberbullying, including self‐report questionnaires, as well as peer‐, parent‐, or teacher‐reports. Studies were excluded if the aggression items were part of a wider measure (e.g., a scale measuring externalizing problems) and a separate effect size was not available. In one case (Hyde, Shaw, & Moilanen, 2010), the original author was able to calculate, upon request, the effect size for aggressive 59 behavior from a broader measure of externalizing problems at the age of 15 and this study was then included in the present meta‐analysis. Second, eligible studies were required to have enough quantitative information to calculate effect sizes. Therefore, studies based on interviews or open‐ended questions were excluded. Third, study participants were school‐age children or adolescents from the community, with studies involving clinical samples or incarcerated offenders, and studies of adults excluded. Finally, both published reports (i.e., journal articles) and unpublished studies (e.g., conference papers, doctoral theses) were considered. In the latter case, data were obtained from the principal investigator or his/her supervisor. When multiple reports (e.g., a conference paper or dissertation and a published article) presented results from the same sample, only one effect size was used in the meta‐analysis. Using these inclusion criteria, the final sample of the current meta‐ analysis included 27 studies; 12 examined the relation between MD and general aggression, 11 considered MD and bullying and four considered MD and cyberbullying (see Table I). All studies were coded independently by the first and the second author, using an a priori coding scheme, recording authors and year of publication, the type and form of MD and aggression measures used (self‐report vs. peer/adult reports), sample size, national setting, and demographic characteristics of participants (age, gender). Inter‐rater agreement was found to be very good; all Cohen’s kappas exceeded .92. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Data Analysis Pearson’s r was used as the effect size metric, because almost all studies provided zero‐order correlation coefficients between the constructs of interest. In three cases (Bacchini, Amodeo, Ciardi, Valerio, & Vitelli, 1998; Del Bove, Caprara, Pastorelli, & Paciello, 2008; Hymel et al., 2005), the effect size was calculated from the comparison between a group of aggressive children and a control (non‐aggressive) group, by first calculating the standardized mean difference and then converting it into r (for details see Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009, p. 48; Card, 2011, p. 100–101). Most studies did not report data separately for boys and girls. Given that one aim of the study was to test the possible moderating role of gender, authors were contacted and asked for ad‐hoc analyses. This resulted in 45 correlation coefficients disaggregated by gender (Hyde et al.’s study only provided boys’ effect size). In four cases for a given study we had two independent effect sizes for each gender (e.g., for primary school boys/girls and for middle school boys/girls). However, the very small numbers of these subgroups did not allow for a more detailed Aggr. Behav. 60 Gini et al. TABLE I. Summary of Studies Included in the Meta‐Analysis Authors (Year) Almeida, Correia, Marinho, and Garcia (in press) Ando et al., (2005) Bacchini et al. (1998) Bandura et al. (1996) Barchia and Bussey (2011) Bauman (2010) Bussey and Quinn (2012) Bussman (2008, study 2) Caprara et al. (1995) Caravita and Gini (2010) Caravita, Gini, and Pozzoli, (2011) Del Bove et al. (2008) Fitzpatrick and Bussey (2012) Gini (2006) Gini et al. (2007b) Gini, Pozzoli, and Hauser (2011) Hyde et al. (2010) Hymel et al. (2005) Menesini, Fonzi, and Vannucci (1999) Obermann (2011) Paciello et al. (2008) Pelton et al. (2004) Perren and Sticca (2011) Pornari and Wood (2010) Qingquan, Zongkui, Fan, and Lei (2009) Stevens and Hardy (in press) Yadava et al. (2001) Sample Size (% of Girls) 499 (47.1%) 2,301 169 799 1,285 190 1,152 136 706 538 879 475 708 581 1,084 719 257 468 652 677 349 245 480 359 1,578 290 200 (49.8%) (46.9%) (45.2%) (53.8%) (54.2%) (37.2%) (52.9%) (43.6%) (46.6%) (47.4%) (45.1%) (57.1%) (49.2%) (50.9%) (48.5%) (0%) (43%) (48.2%) (47.6%) (53.3%) (49.4%) (48.9%) (53%) (48%) (60.3%) (50%) Behavior Measure Shared Method Variance Effect Size: r Spain Cyberbullying, SR Yes .28 Japan Italy Italy Australia United States Australia United States Italy Italy Italy Italy Australia Italy Italy Italy United States Canada Italy Denmark Italy United States Switzerland UK China Samoa India Bullying, SR Bullying, SR Aggression, SR, PN, TR, PR Aggression, SR Cyberbullying, SR Aggression Aggression, PN Aggression, SR, PN, TR Bullying, PN Bullying, PN Aggression, SR Bullying, SR Bullying, PN Bullying, PN Bullying, PN Aggression, PR Bullying, SR Bullying, PN Bullying, SR, PN Aggression, PN Aggression, SR, TR, PR Cyber/Bullying, SR Cyber/Aggression, SR Aggression Aggression Aggression Yes Yes Mixed Yes Yes Yes No Mixed No No Yes Yes No No No No Yes No Mixed No Mixed Yes Yes No Yes Yes .25 .16 .27 .27 .32 .47 .16 .20 .18 .20 .22 .31 .22 .27 .13 .20 .59 .14 .22 .17 .13 .42 .40 .23 .54 .30 Age Range National Setting 11–18 12–15 9–14 10–15 12–15 10–14 12–17 9–12 8–14 9–15 8–15 11–18 12–16 8–11 15–17 9–13 15 13–16 8–14 11–14 12–14 9–14 12–18 12–14 9–11 13–18 15–17 Note. Measures of moral disengagement were all self‐reports. SR, self‐report; PN, peer nominations, TR, teacher‐report; PR, parent‐report. analyses and effect sizes were thus pooled by gender group. In order to avoid violation of the assumption of independence, mean effect sizes for the total sample were calculated for those studies reporting multiple effect sizes (e.g., two or more informants for the same behavior) (Becker, 2000; Borenstein et al., 2009). Outlying effect sizes and sample sizes were identified on the basis of standardized z values larger than 3.29 or smaller than 3.29 (e.g., Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). No outliers were detected for effect size, but there was one study with an outlying sample size (Ando et al., 2005). We winsorized this number of participants (i.e., reduced to the next largest sample size, following Barnett & Lewis, 1994; Lipsey & Wilson, 2000), resulting in an N of 1,578. Data from individual studies were pooled (with comprehensive meta‐analysis program—v.2.2) using a random effects model. To account for variations in sample size, which influences precision with larger samples yielding more precise estimates than smaller samples, each study was weighted by the inverse of its variance (Hedges & Olkin, 1985). Moreover, because the Aggr. Behav. use of correlation coefficients can result in problematic error formulation, the correlation coefficient for each study was converted to the Fisher’s z scale, and all analyses were performed using the transformed values (Lipsey & Wilson, 2000; Rosenthal, 1991). Then, the resulting summary effect and its confidence interval were converted back to correlations for ease of interpretation. A 95% confidence interval (CI) was computed around each mean effect size. Confidence intervals not including zero were interpreted as indicating a statistically detectable result favoring the association between MD and aggressive behavior. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Q statistic (which is distributed as x2 with df ¼ k 1, where k represents the number of effect sizes; Lipsey & Wilson, 2000), evaluating whether the pooled studies represented a homogeneous distribution of effect sizes. Significant heterogeneity indicates that variations in effect sizes are likely due to sources other than sampling error (e.g., study characteristics). Also reported is the I2 statistic, indicating the proportion of observed variance that reflects real differences in effect size (Higgins, Moral Disengagement and Aggressive Behavior Thompson, Deeks, & Altman, 2003). Moderator analyses were conducted to examine this variability. Even though we were able to include several unpublished studies, we evaluated the potential “publication bias” in different ways. We computed the “fail‐safe N” (Nfs) according to the method proposed by Orwin (1983), which is more conservative than the traditional Rosenthal’s Nfs (Rosenthal, 1978, 1979). Orwin’s Nfs determines the number of additional studies yielding null results that would be needed to reduce meta‐analytic results to a negligible result of .05 (Durlak & Lipsey, 1991). We also inspected the funnel plot, which displays effect sizes plotted against the sample size, standard error, or some other measure of the precision of the estimate. An unbiased sample of studies would ideally show a cloud of data points that is symmetric around the population effect size (Field & Gillett, 2010). Moreover, the association between the effect sizes and the variances of these effects was analyzed by rank correlation with use of the Kendall’s t method. If small studies with negative results were less likely to be published, the correlation between variance and effect size would be high. Conversely, lack of significant Study correlation can be interpreted as absence of publication bias (Begg & Mazumdar, 1994). RESULTS Association Between MD and Aggressive Behavior The 27 studies examining the association between MD and aggressive behavior reported data on 17,776 participants aged 8–18. The distribution of effect sizes is presented in Figure 1. Under the random effects model, the mean effect size for the association between MD and aggressive behavior was r ¼ .28, which was significantly different from zero (Z ¼ 11.06, P <.001), with a 95% CI ranging from .23 to .32. The Nfs of null results needed to overturn this significant result suggested that there would need to be at least 127 studies with a null effect size added to the analysis before the cumulative effect would become negligible. In order to evaluate the existence of publication bias, a funnel plot of standard errors plotted against effect sizes was developed. The funnel plot indicated no systematic publication bias, with Statistics for each study Correlation Almeida et al. (in press) Ando et al. (2005) Bacchini et al. (1998) Bandura et al. (1996) Barchia & Bussey (2011) Bauman (2010) Bussey & Quinn (2012) Bussman (2007, study 2) Caprara et al. (1995) Caravita & Gini (2010) Caravita et al. (2011) Del Bove et al. (2008) Fitzpatrick & Bussey (2012) Gini (2006) Gini et al. (2007b) Gini, Pozzoli, Hauser (2011) Hyde et al. (2010) Hymel et al. (2005) Menesini et al. (1999) Obermann (2011) Paciello et al. (2008) Pelton et al. (2004) Perren & Sticca (2011) Pornari & Wood (2010) Qingquan et al. (2009) Stevens & Hardy (in press) Yadava et al. (2001) 0,28 0,25 0,16 0,27 0,27 0,32 0,48 0,16 0,20 0,18 0,20 0,22 0,31 0,22 0,27 0,13 0,20 0,59 0,14 0,22 0,17 0,13 0,42 0,40 0,23 0,54 0,30 0,28 Lower limit 0,20 0,21 0,01 0,21 0,22 0,19 0,43 -0,01 0,13 0,10 0,11 0,14 0,25 0,15 0,22 0,05 0,08 0,53 0,06 0,15 0,06 0,00 0,34 0,31 0,18 0,46 0,16 0,26 Upper limit 0,36 0,28 0,30 0,34 0,32 0,44 0,52 0,32 0,27 0,26 0,29 0,30 0,38 0,30 0,33 0,21 0,31 0,64 0,21 0,30 0,27 0,25 0,49 0,49 0,28 0,62 0,42 0,29 61 Correlation and 95% CI Z-Value p-Value 6,41 12,09 2,09 7,90 9,99 4,54 17,51 1,84 5,30 4,21 4,13 4,97 8,64 5,48 9,17 3,32 3,23 16,06 3,49 5,86 3,14 2,03 9,70 7,87 9,29 10,64 4,28 37,45 0,00 0,00 0,04 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,07 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,04 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 -1,00 -0,50 Favours A 0,00 0,50 1,00 Favours B Fig. 1. Forest plot for random‐effects meta‐analysis of the association between moral disengagement and aggressive behavior. Note. Studies are represented by symbols whose area is proportional to the study’s weight in the analysis. Aggr. Behav. 62 Gini et al. TABLE II. Tests of Categorical Moderators 95% Confidence Interval Study Characteristics Type of behavior Aggression Bullying Cyberbullying Gender Boys Girls Age group Children (8–11 years) Adolescents (12–18 years) Type of MD scale Bandura’s original Bandura‐revised Others Shared method variance Yes No Mixed Publication status Published Not published Between‐Group Effect (Qb) Effect Size (r) Lower Limit Upper Limit k N .27 .25 .31 .20 .17 .27 .34 .32 .36 12 11 4 7,472 8,776 1,528 .26 .26 .21 .21 .31 .31 23 22 5,704 5,267 .18 .31 .14 .26 .22 .36 10 22 4,201 12,326 .24 .31 .36 .19 .23 .07 .28 .38 .60 16 8 3 8,734 7,939 1,103 .35 .20 .24 .28 .17 .15 .42 .23 .33 13 10 4 8,576 6,773 2,427 .27 .29 .21 .20 .33 .37 19 8 11,516 6,260 2.63 0.001 13.47 62.80 14.89 0.14 Note. k indicates the number of independent subsamples; N indicates the number of participants. P <.05. P <.01. P <.001. studies distributed symmetrically about the mean effect size. This was confirmed by the Egger’s test, which yielded a statistically non‐significant P‐value of 0.48 (one‐tailed), and by the rank correlation Kendall’s t ¼ .06, P ¼.66. Moderator Effects The test of homogeneity of variance revealed significant heterogeneity across studies, Q ¼ 271.05, P <.001, I2 ¼ 90.41%. Therefore, mixed effects moderator analyses were conducted to examine the association between study characteristics and their effect sizes. The mixed effects model assumes that the variability in effect sizes consists of systematic variance (that can be statistically modeled), sampling error, and an additional, unexplainable random component. Using the random effects model to combine studies within subgroups in the moderator analyses, a mixed effects model typically allows for population parameters to vary across studies, reducing the probability of Type I error, and is usually regarded as a more rigorous meta‐analytical model than a fixed effect model only (Borenstein et al., 2009; Hedges & Vevea, 1998). The results of the moderator analyses are summarized in Table II. Furthermore, to enhance Aggr. Behav. interpretability of moderation results, especially in cases of multiple categories, we report contrasts of correlations (with their 95% CIs) between different study categories (Bonett, 2008).2 First, we analyzed the existence of any difference in effect size as a function of the type of behavior measured. Only four of the studies reported data for cyberbullying and two of them (Perren & Sticca, 2011; Pornari & Wood, 2010) reported data for both traditional aggression/bullying and cyberbullying from the same sample. To avoid dependence of data, we first ran a moderation analysis excluding the effect sizes about cyberbullying and comparing the 12 studies that measured aggression with the 11 studies that measured bullying. The mean effect size in these two subgroups was very similar (r ¼ .27 and .25, respectively). Subsequently, the subgroup of studies assessing cyberbullying was included in the analysis (with the exclusion of relative MD‐aggression/bullying effect size), yielding a non‐significant between‐group difference: Q(2) ¼ 2.63, P ¼.27. The contrast between bullying and cyberbullying effect sizes yielded a value of .06, 95% CI 2 We thank an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion. Moral Disengagement and Aggressive Behavior [.15, .02]. The contrast between aggression and cyberbullying yielded a value of .04 [.13, .04]. A second moderator analysis compared the effect sizes observed for boys versus girls. Interestingly, the effect of sex was not significant, with the effect sizes from the two sex groups being identical. Potential age differences were tested by comparing effect sizes observed for children (i.e., 8‐ to 11‐year olds) versus adolescents (i.e., 12‐ to 18‐year olds). Four studies provided two independent effect sizes each, one for children and one for adolescents. Two studies (Bacchini et al., 1998; Bauman, 2010) were excluded because separate effect sizes for the two age‐groups were not available. The analysis revealed a significant difference between the two age‐groups favoring adolescents: Q(1) ¼ 13.47, P <.001 (contrast: .13, 95% CI [.19, .06]). Because some studies included a wider range of adolescent ages (until 18 years) compared to others, and Paciello et al. (2008) have reported changes in MD particularly during middle‐ adolescence (14–16‐years), a sensitivity analysis was performed. Exclusion of the samples with participants older than 15 (Bussey & Quinn, 2012; Del Bove et al., 2008; Fitzpatrick & Bussey, 2012; Gini, Albiero, Benelli, Matricardi, & Pozzoli, 2007b; Perren & Sticca, 2011; Stevens & Hardy, 2013; Yadava et al., 2001) did not change this result (Q(1) ¼ 4.48, P ¼.03, with adolescents’ effect size r ¼ .27). In sum, the associations observed between aggression/bullying and MD did not vary as a function of gender but were stronger among adolescents, as compared to children. Moderation analysis by type of MD scale yielded a significant between‐group difference: Q(2) ¼ 62.80, P <.001. The contrast between studies that used the original scale devised by Bandura and those that used a revised version of that scale yielded a value of .07, 95% CI [.16, .02], indicating that the effect tended to be slightly higher in the latter studies. The contrast between studies that used the original scale and those that used a different MD scale yielded a value of .12 [.36, .17]. Finally, the contrast between studies that used a revised version of Bandura’s scale and those that used a different scale yielded a value of .05 [.30, .25]. In order to consider the possible effect of shared method variance, we distinguished studies with shared method variance, studies with no shared method variance, and studies that employed both self‐reports and other informants to measure aggression (“mixed” studies). The analysis revealed a significant between‐ group heterogeneity: Q(2) ¼ 14.89, P ¼.001. Studies with shared method variance reported significantly higher effect sizes relative to those that employed different informants (Q(1) ¼ 14.73, P <.001). The contrast between studies with shared method variance and studies without this problem yielded a value of .15, 63 95% CI [.07, .23], whereas the difference between the former and studies with mixed method was .11 [.004, .22]. Finally, mean effect sizes did not vary as a function of publication status (Q(1) ¼ 0.14, P ¼.71; contrast: .02, [.12, .09]). DISCUSSION A meta‐analytic review of 27 independent studies was conducted to summarize current research on the link between MD and aggressive behavior in children and adolescents and to test whether differences in the reported effects can be explained by the type of aggressive behavior considered, characteristics of the participants, and/or methodological features of the studies. Of interest was computation and interpretation of effect sizes in order to determine whether the magnitude of the effect represents something psychologically important. In doing so, one possibility is to compare a computed effect size with “standard” cut‐off criteria. For example, Cohen (1992) proposed conventional values as benchmarks for what are considered to be “small,” “medium,” and “large” effects (r: .1, .3, and .5, respectively). More recently, based on empirical findings, Hemphill (2003) recommended a reconceptualization of effect sizes in psychological research, in which r ¼ .1 is “small,” r ¼ .2 is “medium,” and r ¼ .3 is “large” (see also Huang, 2011). These benchmarks, however, have been criticized because they are purely conventional, and somewhat arbitrary, whereas practical and clinical importance depends on the situation researchers are dealing with (e.g., Kline, 2004; Thompson, 2002). A preferable solution is to put one effect size into a meaningful context, comparing it to other effects that have been reported within the same literature and are commonly considered important. Such an approach is especially needed when dealing with a multi‐causal phenomenon such as aggressive behavior, where one should not expect any single factor to explain much of the variance (Anderson et al., 2010). The composite effect size yielded by the present meta‐ analysis was small‐to‐medium according to Cohen’s criteria, and medium‐to‐large according to Hemphill’s criteria. A qualitative comparison of our findings with available meta‐analyses on individual risk‐factors and correlates of aggressive behavior in children and adolescents indicates that the MD‐aggressive behavior link is equal—in absolute value—to the association between other‐related cognitions (i.e., children’s thoughts, beliefs, or attitudes about others, including normative beliefs about others, empathy, and perspective taking) and bullying (r ¼ .27; Cook, Williams, Guerra, Kim, & Sadek, 2010). Moreover, the current result is larger than the associations reported between hostile Aggr. Behav. 64 Gini et al. attributions and aggression (r ¼ .17; Orobio de Castro, Veerman, Koops, Bosch, & Monshouwer, 2002), between emotion knowledge and externalizing problems (r ¼ .17; Trentacosta & Fine, 2010), and larger than effect sizes previously reported for other individual predictors of bullying (Cook et al., 2010), such as social competence (r ¼ .15), self‐related cognitions (e.g., self‐ esteem, self‐efficacy, r ¼ .09), social problem‐solving (r ¼ .18), and academic performance (r ¼ .18). In sum, the link between MD and aggressive behavior is both statistically significant and practically meaningful. As expected, significant heterogeneity across effect sizes was also observed, and some significant a priori moderators were identified. Estimated effect size was higher for older participants than for children, indicating the existence of a developmental change in the link between MD and aggressive behavior. As noted in the introduction, Paciello et al. (2008) documented different developmental trajectories of MD during adolescence and found that higher levels of MD increased risk for youth aggression, although such changes were not observed for children. The stronger relation observed between MD and aggression among adolescents relative to children is also consistent with Bandura’s description of MD as a gradual process: “disengagement practices will not instantly transform considerate people into cruel ones. Rather, the change is achieved by progressive disengagement of self‐censure. Initially, individuals perform mildly harmful acts they can tolerate with some discomfort. […] The continuing interplay between moral thought, affect, action and its social reception is personally transformative” (Bandura, 2002, p. 110). In other words, one would expect disengaged justifications and moral transgressions to reinforce each other over time (Bandura et al., 1996; Gibbs, Potter, & Goldstein, 1995). For chronically disengaged adolescents, however, MD could represent a “strategy of adaptation that is embedded into a system of beliefs about the self and others and leads to perceive aggression and violence as appropriate means to pursue one’s own goals” (Paciello et al., 2008, p. 1302). Understanding the nature and mechanisms underlying this developmental shift is an important focus in future research. To this end, it becomes important to develop techniques to assess MD in children below 8 years of age, in order to study when such distortions emerge and their relation to moral development (e.g., the emergence of the distinction between moral and social‐conventional rules) and with environmental factors, such as parenting or early experiences with peers. Finally, future research would benefit from comparisons of developmental changes as documented in cross‐sectional versus longitudinal research. The present meta‐analysis included three longiAggr. Behav. tudinal studies (Barchia & Bussey, 2011; Hyde et al., 2010; Paciello et al., 2008) that differed considerably in design. As a result, we did not feel that the studies were sufficiently comparable to include analyses comparing longitudinal and cross‐sectional studies. Efforts to tease apart variations in moral development and aggression as a function of age, time, or cohort may be a particularly fruitful focus in future research. Notably, effect sizes did not significantly vary as a function of type of aggressive behavior considered (aggression vs. bullying vs. cyberbullying). In the case of cyberbullying, however, the estimated correlation with MD was slightly higher than that observed for traditional aggression/bullying. The contrasts of correlations suggest that cyberbullying may have slightly stronger links with MD, given the CI just hugs zero. However, this analysis was limited by the small number of studies that examined the relation between MD and cyberbullying, which were limited to adolescent samples and were characterized by low precision that resulted in a quite wide confidence interval. Future studies are certainly needed to further explore the issue of moral justifications in online/virtual aggressive relationships. Results of the present meta‐analysis also revealed that the correlation between MD and aggressive behavior did not differ significantly across boys and girls. Even though absolute levels of moral disengagement and aggressive behavior are often higher in boys, the relation between the two variables is identical. These results should be viewed with caution, however, given that the small number of studies in each cell did not allow for a more thorough analysis and we cannot rule out the possibility that gender differences do not exist at different age‐ levels. Results of the present meta‐analysis are important in guiding the design of future studies testing specific hypotheses regarding sex differences. Regarding the possible effect of methodological differences, the link between MD and aggression was moderated by type of MD scale, with the mean effect being slightly larger when MD was measured through a revised version of Bandura’s scale as compared to the original scale. This difference may be due to the fact that, at least in some cases, the revised scale was designed to retain items more explicitly related to disengagement for aggressive acts. In addition, as expected, shared method variance was found to be a significant moderator, with somewhat larger effect sizes observed when the same informant (participating child/youth) evaluated both MD and aggressive behavior. Unfortunately, the very small number of studies using adult informants precluded any further comparisons. Finally, effect sizes did not differ for published versus unpublished studies, supporting the validity of the current meta‐analytic estimations, which were not inflated by publication bias. Moral Disengagement and Aggressive Behavior Limitations and Future Directions Despite the strengths of the present meta‐analysis, it also presents limitations due to the characteristics and quality of the primary studies. One limitation deals with the limited capacity to measure single mechanisms in a reliable and valid manner (e.g., the four broad categories of MD strategies). Indeed, studies to date have treated MD as a unidimensional construct (see Pozzoli, Gini, & Vieno, 2012, for an exception) and we know nothing about whether different MD mechanisms act differently in aggressive behavior nor whether their relative importance varies as a function of age. Conceptually, this may suggest that the psychological function of the MD process—to free the individual from self‐censure and potential guilt—is more important than the specific strategy used to achieve the individual’s self‐serving goal (e.g., justifying the negative behavior enacted vs. blaming the victim). Still, a better understanding of whether and under what circumstances these mechanisms can be differently activated may have both theoretical and practical implications. In this regard, future research may benefit from consideration of new research paradigms and methodologies, in both laboratory and field studies. Future research would also benefit from further consideration of other ways to conceptualize and measure MD. Particularly promising here are studies examining how morally disengaged emotions, such as pride or indifference (instead of guilt or shame) following an aggressive act influence subsequent behavior. Efforts to expand and integrate the two approaches into a coherent theoretical model of MD would be welcomed. Another limitation is that the directionality of the association between MD and aggressive behavior is not clear, and bidirectionality might be the rule instead of the exception. Indeed, MD mechanisms are likely to influence aggressive behavior over time (Hyde et al., 2010; Paciello et al., 2008), but their activation may also be made easier by repeated immoral acts (e.g., Bandura, 1990) and frequent exposure to an aggressive environment can alter children’s evaluation of moral transgression (Ardila‐Rey, Killen, & Brenick, 2009). Unfortunately, this domain of research is still largely dominated by correlational studies that preclude definite conclusions about direction of effects and causality in general. Intervention studies investigating whether changing proneness to MD also changes children’s use of aggression could help to clarify the issue of directionality. Our analyses were limited by the methodological quality of the studies available and we were not able to account for the reliability of the measures used in the studies because such information was not available in many cases. Because score reliability influences 65 observed effect sizes and should be used to interpret those effects, it is important that measurement studies as well as substantive studies systematically report reliability coefficients for their samples. A lack of data also prevented the consideration of additional potential moderators. For example, the samples generally included participants from a variety of SES and ethnic/racial groups, yet no studies reported the association separately for the different groups. Moreover, although the positive association between MD and aggressive behavior is established, in reviewing studies for this meta‐analysis, the lack of research investigating moderators of the association between MD and aggression was readily apparent. Although some studies have shown that the link between MD and aggressive behavior is significant even after the role of other variables are accounted for (e.g., Barchia & Bussey, 2011; Caravita & Gini, 2010; Pelton et al., 2004), little is known about how moral disengagement interacts with other individual risk factors, particularly personality characteristics that make some youth more likely to engage in antisocial conduct, such as aggression. Overall, the individual and contextual factors that may buffer or exacerbate the relation of MD and aggression remains unclear. Given the current findings, it is time to move from “main effect” studies, aimed at establishing a relation between MD and aggressive behavior, to “interaction effect” studies, testing specific hypotheses and more complex patterns of relations. In conclusion, this study presents the first meta‐ analytic synthesis of the research on the relation between MD and aggressive behavior in school‐age children and adolescents. Our results showed that MD can be considered one major correlate of aggressive behavior, and that this relation is moderated by age and shared method variance. It is clear that additional methodologically strong studies are needed to have a more complete understanding of these factors, especially in relation to developmental processes and contextual influences on MD, that will provide useful information for prevention and intervention efforts. REFERENCES References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta‐analysis Almeida, A., Correia, I., Marinho, S., & Garcia, D. (2012). Virtual but not less real: A study of cyberbullying and its relations to moral disengagement and empathy. In Q. Li, D. Cross, & P. K. Smith (Eds.), Cyberbullying in the global playground: Research from international perspectives. (pp. 223–244) Chichester: Wiley‐Blackwell. Anderson, C. A., Shibuya, A., Ihori, N., Swing, E. L., Bushman, B. J., Sakamoto, A., Rothstein, H. R., & Saleem, M. (2010). Violent video Aggr. Behav. 66 Gini et al. game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in Eastern and Western countries: A meta‐analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 151–173. doi: 10.1037/a0018251 Ando, M., Asakura, T., & Simons‐Morton, B. (2005). Psychosocial influences on physical, verbal, and indirect bullying among Japanese early adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence, 25, 268–297. doi: 10.1177/0272431605276933 Andreou, E., & Metallidou, P. (2004). The relationship of academic and social cognition to behavior in bullying situations among Greek primary school children. Educational Psychology, 24, 27–41. doi: 10.1080/0144341032000146421 Ardila‐Rey, A., Killen, M., & Brenick, A. (2009). Moral reasoning in violent contexts: Displaced and non‐displaced Colombian children’s evaluations of moral transgressions, retaliation, and reconciliation. Social Development, 18, 181–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1467‐9507.2008.00483.x Arsenio, W. F., & Lemerise, E. A. (2004 , June). Aggression and moral development: Towards an integration of the social information processing and moral domain models. Poster presented at meeting of Jean Piaget Society, Toronto, Canada. Bacchini, D., Amodeo, A. L., Ciardi, A., Valerio, P., & Vitelli, R. (1998). La relazione vittima‐prepotente: stabilità del fenomeno e ricorso a meccanismi di disimpegno morale. Scienze dell’Interazione, 5, 29–46. Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Bandura, A. (1990). Selective activation and disengagement of moral control. Journal of Social Issues, 46, 27–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1540‐ 4560.1990.tb00270.x Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action. In W. M. Kurtines, & G. L. Gewirtz (Eds.), Handbook of moral behavior and development: theory, research and applications (Vol. 1, pp. 71–129). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Bandura, A. (2002). Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Moral Education, 312, 101–119. doi: 10.1080/0305724022014322 Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 364–374. doi: 10.1037/0022‐3514.71.2.364 Barchia, K., & Bussey, K. (2011). Individual and collective social cognitive influences on peer aggression: Exploring the contribution of aggression efficacy, moral disengagement, and collective efficacy. Aggressive Behavior, 37, 107–120. doi: 10.1002/ab.20375 Barnett, V., & Lewis, T. (1994). Outliers in statistical data (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley. Bauman, S. (2010). Cyberbullying in a rural intermediate school: An exploratory study. Journal of Early Adolescence, 30, 803–833. doi: 10.1177/0272431609350927 Becker, B. J. (2000). Multivariate meta‐analysis. In H. E. A. Tinsley, & S. Brown (Eds.), Handbook of applied and multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling. San Diego: Academic Press. Begg, C. B., & Mazumdar, M. (1994). Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics, 50, 1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446 Bonett, D. G. (2008). Meta‐analytic interval estimation for Pearson correlations. Psychological Methods, 13, 173–189. Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta‐analysis. Chichester, UK: Wiley. Bussey, K., & Quinn, C. (2012 , March). Moral disengagement as the link between the influences of empathy and perspective taking on peer conflict. Paper presented at the 2012 SRA Biennial Meeting, Vancouver, Canada. Bussman, J. R. (2007). Moral disengagement in children’s overt and relational aggression. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 68(7‐B), 4813. Aggr. Behav. Caprara, G. V., Pastorelli, C., & Bandura, A. (1995). Measuring age differences in moral disengagement. Eta Evolutiva, 51, 18–29. Caravita, S. C. S., & Gini, G. (2010 , March). Rule perception or moral disengagement? Associations of moral cognition with bullying and defending in adolescence. Paper presented at the SRA Biennial Meeting. Philadelphia, USA. Caravita, S. C. S., Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2011 , March, April). Moral disengagement for victimization in bullying: Individual or contextual processes? Paper presented at the SRCD Biennial Meeting. Montreal, Canada. Caravita, S. C. S., Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2012). Main and moderated effects of moral cognition and status on bullying and defending. Aggressive Behavior, 38, 456–468. Card, N. A. (2011). Applied meta‐analysis for social science research. New York: Guilford Press. Card, N. A., Stucky, B. D., Sawalani, G. M., & Little, T. D. (2008). Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: A meta‐ analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Development, 79, 1185–1229. doi: 10.1111/ j.1467‐8624.2008.01184.x Carney, A. G., & Merrell, K. W. (2001). Perspectives on understanding and preventing an international problem. School Psychology International, 22, 364–382. doi: 10.1177/0143034301223011 Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155–159. doi: 10.1037/0033‐2909.112.1.155 Cook, C. R., Williams, K. R., Guerra, N. G., Kim, T. E., & Sadek, S. (2010). Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence. School Psychology Quarterly, 25, 65–83. doi: 10.1037/a0020149 Del Bove, G., Caprara, G. V., Pastorelli, C., & Paciello, M. (2008). Juvenile firesetting in Italy: Relationship to aggression, psychopathology, personality, self‐efficacy, and school functioning. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 17, 235–244. doi: 10.1007/s00787‐007‐ 0664‐6 Dodge, K. A., Coie, J. D., & Lynam, D. (2006). Aggression and antisocial behaviour in youth. In W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Series, Eds.) & N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (pp. 719–788). New York: Wiley. Durlak, J. A., & Lipsey, M. W. (1991). A practitioner’s guide to meta‐ analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology, 19, 291–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00938026 Field, A. P., & Gillett, R. (2010). How to do a meta‐analysis. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 63, 665–694. doi: 10.1348/000711010X502733 Fitzpatrick, S., Bussey, K. (2012 , March). The influence of moral disengagement on social bullying in dyadic very best friendships. Paper presented at the SRA Biennial Meeting, Vancouver, Canada. Gibbs, J., Potter, G., & Goldstein, A. (1995). The EQUIP program: Teaching youth to think and act responsibly through a peer‐helping approach. Champaign, IL: Research Press. Gini, G. (2006). Social cognition and moral cognition in bullying: What’s wrong? Aggressive Behavior, 32, 528–539. doi: 10.1002/ab.20153 Gini, G., Albiero, P., Benelli, B., & Altoè, G. (2007a). Does empathy predict adolescents’ bullying and defending behavior? Aggressive Behavior, 33, 467–476. doi: 10.1002/ab.20204 Gini, G., Albiero, P., Benelli, B., Matricardi, G., Pozzoli, T. (2007b , August). Association between empathy, social intelligence, moral disengagement and different forms of bullying behaviour in Italian adolescents. Paper presented at the 13th European Conference on Developmental Psychology, Jena, Germany. Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2006). The role of masculinity in children’s bullying. Sex Roles, 7/8, 585–588. doi: 10.1007/s11199‐006‐9015‐1 Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2009). Association between bullying and psychosomatic problems: A meta‐analysis. Pediatrics, 123, 1059– 1065. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008‐1215 Moral Disengagement and Aggressive Behavior Gini, G., Pozzoli, T. (2013). Being bullied and psychosomatic problems: A meta‐analysis. Pediatrics. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0614 Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Hauser, M. (2011). Bullies have enhanced moral competence to judge relative to victims, but lack moral compassion. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 603–608. doi: 10.1016/j. paid.2010.12.002 Hawker, D. S. J., & Boulton, M. J. (2000). Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta‐analytic review of cross‐sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 41(4), 441–455. doi: 10.1111/1469‐ 7610.00629 Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta‐analysis. Orlando, FL: Academic Press. Hedges, L. V., & Vevea, J. L. (1998). Fixed and random‐effects models in meta‐analysis. Psychological Methods, 3, 486–504. doi: 10.1037/ 1082‐989X.3.4.486 Hemphill, J. F. (2003). Interpreting the magnitudes of correlation coefficients. American Psychologist, 58, 78–79. doi: 10.1037/0003‐ 066X.58.1.78 Higgins, J., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. British Medical Journal, 327, 557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 Hodgdon, H. B. (2010). Child maltreatment and aggression: The mediating role of moral disengagement, emotion regulation, and emotional callousness among juvenile offenders. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 70(9‐B), 5822. Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T¼JS&PAGE¼ reference&D¼psyc6&NEWS¼N&AN¼2010‐99061‐047. Huang, C. (2011). Self‐concept and academic achievement: A meta‐ analysis of longitudinal relations. Journal of School Psychology, 49, 505–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2011.07.001 Hyde, L., Shaw, D., & Moilanen, K. (2010). Developmental precursors of moral disengage‐ment and the role of moral disengagement in the development of antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 197–209. doi: 10.1007/s10802‐009‐9358‐5 Hymel, S., Rocke Henderson, N., & Bonanno, R. A. (2005). Moral disengagement: A framework for understanding bullying among adolescents [Special issue]. Journal of Social Sciences, 8, 1–11. Hymel, S., Schonert‐Reichl, K. A., Bonanno, R. A., Vaillancourt, T., & Rocke Henderson, N. (2010). Bullying and morality. Understanding how good kids can behave badly. In S. R. Jimerson, S. M. Swearer, & D. L. Espelage (Eds.), Handbook of bullying in schools. An international perspective (pp. 101–118). New York: Routledge. Jolliffe, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2011). Is low empathy related to bullying after controlling for individual and social background variables? Journal of Adolescence, 34, 59–71. doi: 0.1016/j.adolescence. 2010.02.001 Kiriakidis, S. P. (2008). Moral disengagement: Relation to delinquency and independence from indices of social dysfunction. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 52, 571–583. doi: 10.1177/0306624X07309063 Kline, R. B. (2004). Beyond significance testing. Washington, DC: APA. Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2000). Practical meta‐analysis (Vol. 49). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. Malti, T., Gasser, L., & Gutzwiller‐Helfenfinger, E. (2010). Children’s interpretive understanding, moral judgment, and emotion attributions: Relations to social behaviour. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 28(2), 275–292. doi: 10.1348/026151009X403838 Menesini, E., Fonzi, A., & Vannucci, M. (1999). Il disimpegno morale: la legittimazione del comportamento prepotente. In Fonzi, A, (Ed.), Il gioco crudele. Studi e ricerche sui correlati psicologici del bullismo (pp. 39–53). Firenze: Giunti. Menesini, E., Nocentini, A., & Camodeca, M. (2013). Morality, values, traditional bullying, and cyberbullying in adolescence. British Journal 67 of Developmental Psychology, 31, 1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.2044‐835X. 2011.02066.x Menesini, E., Sanchez, V., Fonzi, A., Ortega, R., Costabile, A., & Lo Feudo, G. (2003). Moral emotions and bullying: A cross‐national comparison of differences between bullies, victims and outsiders. Aggressive Behavior, 29, 515–530. doi: 10.1111/1467‐9507.00121 Obermann, M. L. (2011). Moral disengagement in self‐reported and peer‐ nominated school bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 37, 133–144. doi: 10.1002/ab.20378 Orobio de Castro, B., Veerman, J. W., Koops, W., Bosch, J. D., & Monshouwer, H. J. (2002). Hostile attribution of intent and aggressive behavior: A meta‐analysis. Child Development, 73, 916–934. doi: 10.1111/1467‐8624.00447 Orwin, R. G. (1983). A fail‐safe N for effect size in meta‐analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 8, 157–159. doi: 10.3102/ 10769986008002157 Paciello, M., Fida, R., Tramontano, C., Lupinetti, C., & Caprara, G. V. (2008). Stability and change of moral disengagement and its impact on aggression and violence in late adolescence. Child Development, 79, 1288–1309. doi: 10.1111/j.1467‐8624.2008.01189.x Pelton, J., Gound, M., Forehand, R., & Brody, G. (2004). The moral disengagement scale: Extension with an American minority sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26, 31–39. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007454.34707.a5 Pepler, D., Jiang, D., Craig, W., & Connolly, J. (2008). Developmental trajectories of bullying and associated factors. Child Development, 79, 325–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1467‐8624.2007.01128.x Perren, S., & Sticca, F. (2011 , March). Bullying and morality: Are there differences between traditional bullies and cyberbullies? Poster presented at the SRCD Biennial Meeting, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Pornari, C. D., & Wood, J. (2010). Peer and cyber aggression in secondary school students: The role of moral disengagement, hostile attribution bias, and outcome expectancies. Aggressive Behavior, 36, 81–94. doi: 10.1002/ab.20336 Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Vieno, A. (2012). Individual and class moral disengagement in bullying among elementary school children. Aggressive Behavior, 38, 378–388. Qingquan, P., Zongkui, Z., Fan, P., & Lei, H. (2009). Moral disengagement in middle childhood: Influences on prosocial and aggressive behaviors. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Information Science and Engineering (pp. 3361–3364). doi: 10.1109/ICISE.2009.760 Ribeaud, D., & Eisner, M. (2010). Are moral disengagement, neutralization techniques and self‐serving cognitive distortions the same? Developing a unified scale of moral neutralization of aggression. International Journal of Conflict & Violence, 4, 298–315. Rigby, K., & Slee, P. T. (1993). Dimensions of interpersonal relating among Australian school children and their implications for psychological well‐being. Journal of Social Psychology, 133, 33–42. doi: 10.1080/ 00224545.1993.9712116 Rosenthal, R. (1978). Combining results of independent studies. Psychological Bulletin, 85, 185–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1420‐9101.2005. 00917.x Rosenthal, R. (1979). The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86, 638–641. doi: 10.1037/0033‐ 2909.86.3.638 Rosenthal, R. (1991). Meta‐analytic procedures for social research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Shulman, E. P., Cauffmann, E., Piquero, A. R., & Fagan, J. (2011). Moral disengagement among serious juvenile offenders: A longitudinal study of the relations between morally disengaged attitudes and offending. Developmental Psychology, 47, 1619–1632. doi: 10.1037/a0025404 Smith, P. K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school Aggr. Behav. 68 Gini et al. pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 376–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1469‐7610.2007.01846.x Stevens, D. L., & Hardy, S. A. (2013). Individual, family, and peer predictors of violence among Samoan adolescents. Youth & Society, 45, 428–449. doi: 10.1177/0044118X11424756 Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7, 321–326. doi: 10.1089/1094931041291295 Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.) Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Thompson, B. (2002). ‘Statistical’, ‘practical’, and ‘clinical’: How many kinds of significance do counselors need to consider. Journal of Counseling & Development, 80, 64–71. doi: 10.1002/j.1556‐6678. 2002.tb00167.x Tisak, M. S., Tisak, J., & Goldstein, S. E. (2006). Aggression, delinquency, and morality: A social‐cognitive perspective. In M. Killen, & J. Smetana (Eds.), Handbook of Moral Development (pp. 611–632). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Aggr. Behav. Trentacosta, C. J., & Fine, S. E. (2010). Emotion knowledge, social competence, and behavior problems in childhood and adolescence: A meta‐analytic review. Social Development, 19, 1–29. doi: 10.1111/ j.1467‐9507.2009.00543.x Ttofi, M. M., Farrington, D. P., Losel, F., & Loeber, R. (2011). The predictive efficiency of school bullying versus later offending: A systematic/meta‐analytic review of longitudinal studies. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health, 21, 80–89. doi: 10.1002/cbm.808 Vaillancourt, T., Hymel, S., Duku, E., Krygsman, A., Cunningham, L., Davis, C., Short, K., Cunningham, C. (2006 , July). Beyond the Dyad: An analysis of the impact of group attitudes and behavior on bullying. Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development, Melbourne Australia. Yadava, A., Sharma, N. R., & Gandhi, A. (2001). Aggression and moral disengagement. Journal of Personality and Clinical Studies, 17(2), 95–99.