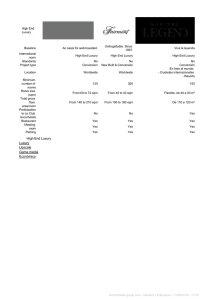

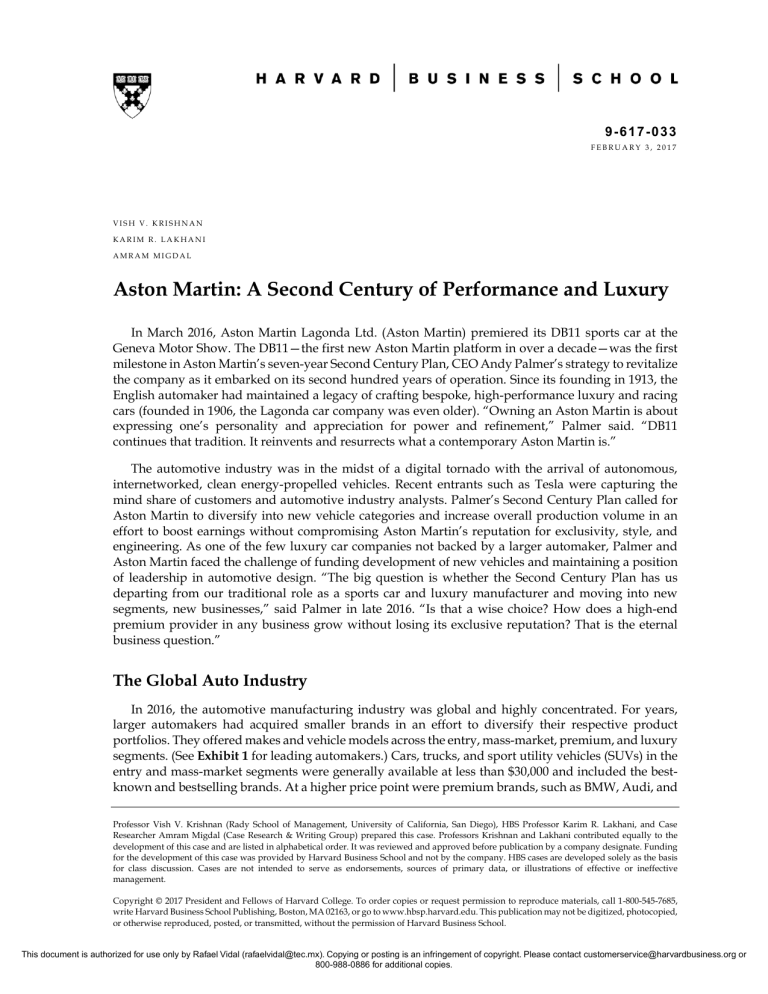

9-617-033 FEBRUARY 3, 2017 VISH V. KRISHNAN KARIM R. LAKHANI AMRAM MIGDAL Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury In March 2016, Aston Martin Lagonda Ltd. (Aston Martin) premiered its DB11 sports car at the Geneva Motor Show. The DB11—the first new Aston Martin platform in over a decade—was the first milestone in Aston Martin’s seven-year Second Century Plan, CEO Andy Palmer’s strategy to revitalize the company as it embarked on its second hundred years of operation. Since its founding in 1913, the English automaker had maintained a legacy of crafting bespoke, high-performance luxury and racing cars (founded in 1906, the Lagonda car company was even older). “Owning an Aston Martin is about expressing one’s personality and appreciation for power and refinement,” Palmer said. “DB11 continues that tradition. It reinvents and resurrects what a contemporary Aston Martin is.” The automotive industry was in the midst of a digital tornado with the arrival of autonomous, internetworked, clean energy-propelled vehicles. Recent entrants such as Tesla were capturing the mind share of customers and automotive industry analysts. Palmer’s Second Century Plan called for Aston Martin to diversify into new vehicle categories and increase overall production volume in an effort to boost earnings without compromising Aston Martin’s reputation for exclusivity, style, and engineering. As one of the few luxury car companies not backed by a larger automaker, Palmer and Aston Martin faced the challenge of funding development of new vehicles and maintaining a position of leadership in automotive design. “The big question is whether the Second Century Plan has us departing from our traditional role as a sports car and luxury manufacturer and moving into new segments, new businesses,” said Palmer in late 2016. “Is that a wise choice? How does a high-end premium provider in any business grow without losing its exclusive reputation? That is the eternal business question.” The Global Auto Industry In 2016, the automotive manufacturing industry was global and highly concentrated. For years, larger automakers had acquired smaller brands in an effort to diversify their respective product portfolios. They offered makes and vehicle models across the entry, mass-market, premium, and luxury segments. (See Exhibit 1 for leading automakers.) Cars, trucks, and sport utility vehicles (SUVs) in the entry and mass-market segments were generally available at less than $30,000 and included the bestknown and bestselling brands. At a higher price point were premium brands, such as BMW, Audi, and Professor Vish V. Krishnan (Rady School of Management, University of California, San Diego), HBS Professor Karim R. Lakhani, and Case Researcher Amram Migdal (Case Research & Writing Group) prepared this case. Professors Krishnan and Lakhani contributed equally to the development of this case and are listed in alphabetical order. It was reviewed and approved before publication by a company designate. Funding for the development of this case was provided by Harvard Business School and not by the company. HBS cases are developed solely as the basis for class discussion. Cases are not intended to serve as endorsements, sources of primary data, or illustrations of effective or ineffective management. Copyright © 2017 President and Fellows of Harvard College. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, call 1-800-545-7685, write Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston, MA 02163, or go to www.hbsp.harvard.edu. This publication may not be digitized, photocopied, or otherwise reproduced, posted, or transmitted, without the permission of Harvard Business School. This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. 617-033 Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury Mercedes-Benz, which could retail for up to $100,000. At the top of the market were luxury brands, which were generally only affordable to wealthy individuals. Consolidation and diverse product portfolios allowed the big manufacturers to save on development by sharing modular components across product lines. Often, outwardly distinct makes and models in different market segments were, in fact, based on the same underlying design platforma and shared parts from engines to electrical systems, body elements, and infotainment features (built-in information and entertainment technologies). For instance, the Volkswagen (VW) Touareg shared the same 3.6 liter 6-cylinder (V6) engine and other elements of its platform with the Audi Q7 and had components developed both independently and collaboratively by VW, Audi, and Porsche. Likewise, the Audi Q7 shared much of its structure with the Bentley Bentayga, an SUV from VW’s luxury marque. (See Appendix A.) Luxury Market Together, premium and luxury cars and trucks amounted to 14% of global sales volume (out of 68.6 million passenger cars worldwide)1 and 60% of industry profits.2 Prices for luxury vehicles could start at well over $100,000. Production volumes were in the tens of thousands annually, a fraction of the millions of units that bestselling mass-market brands produced each year. Most luxury auto brands were backed by a larger manufacturer, including Fiat’s Maserati, BMW’s Roll Royce, and VW’s Lamborghini and Bentley (see Appendix B for luxury brands). Other notable marques included Ferrari, McLaren, and Aston Martin. Sales of high-end vehicles were increasing especially in Asia and the Middle East.3 From 2001 to 2014, China saw premium and luxury car sales grow by 50%.4 Luxury brands catered to the small but growing global population of high net worth (HNW) and ultra-high net worth (UHNW) consumers, commonly defined as those whose investable assets totaled over $1 million or $30 million, respectively. In 2015, 172,850 individuals with total wealth of $20.8 trillion made up the UHNW group worldwide.5 By 2024, the group was expected to increase by another 34%.6 This group spent their fortunes in part on luxury goods ranging from watches to diamonds, jewelry, wine, art, and fine cars.7 According to research analysts, “personal pleasure is the main reason most [UHNW individuals] like to collect beautiful and pleasurable things, [although] one suspects that even the most epicurean collectors would prefer that their treasures grow in value.”8 Luxury brands often produced items of cutting-edge design that expressed the owner’s identity rather than focusing on utilitarian or functional qualities. Such brands often had fabled histories and reputations for fine craftsmanship. For example, luxury auto brands such as Aston Martin and Ferrari not only produced high-performance consumer cars but also developed concept cars that pushed the boundaries of design and technology, as well as racing platforms that competed in Formula 1 races and other competitions. Technology Trends In 2016, three technology trends were having a profound impact on the auto industry more broadly: hybrid and electric engines and progress toward zero-emissions vehicles (0EV); autonomous driving capabilities; and network-connected features. One observer noted, “Connectivity, and later autonomous technology, will increasingly allow the car to become a platform for drivers and passengers to use their time in transit to consume novel forms of media and services or dedicate the freed-up time to other personal activities. The increasing speed of innovation, especially in softwarebased systems, will require cars to be upgradable.”9 Vehicle launch cycles typically were three to four years, while software updates operated on a timescale of months or days. Since 2005, the cost of a Auto manufacturers typically developed different vehicle makes and models based on common design platforms. Platforms consisted of modular components, shared engineering, and standardized production processes used across variants of a particular model or even for distinct makes and models. 2 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury 617-033 electronics and software had dropped by more than 80%, and in 2015 electronics innovations accounted for 90% of new features in the auto industry.10 Meanwhile, stricter emissions standards and technological advances were spurring innovation in hybrid and electric engines. In 2016, U.S. federal regulations, called the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards, began going into effect. CAFE standards required that by 2025, manufacturers’ fleets’ average fuel economies be 54.5 miles per gallon (mpg), up from 27.5 mpg in 2012.11 Europe, China, and India all heavily taxed fuel and had put in place strict emissions standards.12 Palmer believed electrified vehicles would make up 25% of the overall market by 2025. New entrants whose strategies focused on 0EV, automation, and connected features included the electric car maker Tesla and Google’s self-driving car. Tesla’s and Google’s offerings were aimed specifically at disrupting the entry and mass-market segments of the market by developing vehicles that could sell for $35,000 or under. “One could argue that Google’s car is actually a set of technologies that will go onto other cars. They may be changing course and not producing their own car,” said Aston Martin Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) Simon Sproule. The same segments were under threat of disruption from other technology, as well, including car-sharing services such as Uber. One report predicted that “car sharing will cost OEMs [original equipment manufacturers] approximately 550,000 units in worldwide vehicle sales. In revenue terms, that works out to €7.4 billion in net lost revenues, once the impact of forgone purchases, increased car sharing, and car-sharing fleet sales is taken into account.”13 The report stated that by 2021, car-sharing fleet sales would replace only about one third of the reduction in private purchases due to the availability of car sharing.14 Aston Martin: An English Automotive Classic Since its founding, Aston Martin had been owned and run primarily by auto enthusiasts who were passionate about creating high-performance luxury driving machines. It was a low-volume manufacturer that catered to a small but profitable market of wealthy collectors and hobbyists. “An Aston Martin is a collector’s item, often the third or fourth car in an owner’s garage,” Palmer said. “Owning one expresses something individual about society and good taste.” Aston Martin was known for the quality of its engineering and design, particularly its bonded-aluminum bodies and bespoke, handcrafted assembly. Its cars displayed meticulous attention to style, from a model’s silhouette to its manually-stitched Scottish leather interiors. In its 103-year history, Aston Martin had produced a total of 80,000 units, 95% of which were still in running condition (see Exhibit 2 for historical production volume). Despite its history and storied reputation, the company never achieved consistent profitability and underwent a variety of ownership transitions and organizational re-configurations. History of Aston Martin Founding In 1913, racing driver Lionel Martin partnered with engineer Robert Bamford to produce and race their own cars out of a small London workshop. In 1914, they began manufacturing sports cars commercially and named the company Aston Martin after Martin competed on a hill climb course—a set of timed auto racing events—near the town of Aston Clinton, England. In 1920, Bamford departed, and in 1926, after several bankruptcies, Martin sold the company. In its first 13 years, Aston Martin had built about 60 cars, along with a reputation for blending power and style. Over the next 20 years, Aston Martin remained formidable on the race track, excelling in competitions such as Le Mans. It produced a number of well-regarded luxury models, including sports cars and luxury sedans, called saloons. Nevertheless, the company was forced to refinance several more times. 3 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. 617-033 Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury Acceleration in the “DB” era In 1947, Sir David Brown, a prominent British businessman who loved cars and ran a large engineering firm founded by his grandfather, was seeking to create an English sports car company to rival Italy’s Ferrari.15 Seeing an advertisement for the sale of an unnamed sports car company in The Times of London, he soon discovered it was for the famous but troubled Aston Martin. He immediately purchased the company.16 He then promptly bought a second venerable British luxury marque, Lagonda, which was known for its saloons and engines designed by the famous W.O. Bentley. Soon, Aston Martin was producing a new line of cars named for Brown’s initials, DB, the first of which debuted in 1948, followed by the DB2 in 1950. Under Brown, Aston Martin’s reputation for superb driving quality, refined style, and top-notch engineering grew. In 1963, the DB5 premiered—the first Aston Martin car to feature an all-aluminum engine and to display Aston Martin’s budding expertise at using the lightweight material in place of steel. A total of 1,059 DB5s were built, and it came to be considered an iconic model. It was also the first Aston Martin to appear in a James Bond film—1964’s Goldfinger. Despite the acclaim of its cars, Aston Martin consistently failed to break even, and Brown sold the company in 1972.17 Ford From 1967 to 1987, the company changed hands several times. Although it continued to put out well-respected cars during that span—for example, the DBS and the V8 Vantage—it launched no major new platforms and produced just 5,000 total vehicles. At times, production dropped to as low as three units per week. In 1987, the Ford Motor Company (Ford) took a partial stake in Aston Martin, and in 1988 the company released its first major new sports car platform in 20 years, the Virage. In 1993, Ford consolidated control of the company and revived the DB moniker with the debut of the DB7 platform. In 1995, Aston Martin set a company record by manufacturing 700 vehicles in a single year. In 2000, Dr. Ulrich Bez was appointed CEO and chairman. Acquiring Aston Martin was part of Ford’s strategy to expand its presence in the premium and luxury segments. Ford had acquired Jaguar in 1989 and Volvo in 1999, placing both brands in its Premier Automotive Group (PAG). In 2000, the PAG added Land Rover, maker of premium SUVs including the Range Rover, and combined it with Jaguar. PAG represented Ford’s attempt to capitalize on shared knowledge, common production components, and joint facilities between brands. In 2003, Aston Martin moved to a purpose-built facility in Gaydon—directly across the road from the facilities of Jaguar Land Rover (JLR). In 2004, Aston Martin moved its V8 and V12 engine production to Ford’s plant in Cologne, Germany, helping to boost capacity to 5,000 engines per year and achieve economies of scale that freed the Gaydon factory to focus on specialty models with smaller production runs. Private Ownership In March 2007, as part of a series of divestments following its use of financing arranged by the U.S. government, Ford sold all but 15% of its stake in Aston Martin. (Ford also sold off JLR, which was bought by the Indian automaker Tata Motors for $2.3 billion.)18 A consortium led by Middle Eastern firms Investment Dar and Adeem Investment and organized by David Richards, a wealthy racing enthusiast and chief executive of Prodrive, an English automotive technology company, paid $925 million for a controlling interest. Richards became chairman and Bez remained as CEO.19 Then, in December 2012, European private equity shop Investindustrial purchased 37.5% of Aston Martin for $246 million.20 In 2012, ownership budgeted $785 million toward developing a new sports car platform and revamping existing sports car models. A year later, auto-giant Daimler AG, parent of Mercedes-AMG, took a 5%, non-voting ownership stake and agreed to collaborate on development of V8 engines for upcoming Aston Martin models.21 “The deal will help Aston Martin, the only global luxury car maker not attached to a larger manufacturer, spread the cost of developing new fuel-efficient vehicles. The two car makers also plan to cooperate on the supply of electronic components,” stated one report.22 4 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury 617-033 Under the leadership of auto sports enthusiasts Richards and Bez, Aston Martin built on its legacy of cutting-edge design by focusing on racing and concept cars. Executive Vice President (VP) and Chief Creative Officer (CCO) Marek Reichman had contributed to the designs of the Rolls Royce Phantom, the Lincoln MKX, and other concept cars considered to be among the best recent auto designs in the world. He aimed to design vehicles that represented the height of luxury style, “Collectible cars with enormous longevity,” as he put it.23 The brand’s prestige was perhaps best captured in the company’s long-running association with the James Bond movie franchise. By 2015, the super spy had been depicted behind the wheel of an Aston Martin in 12 feature films (see Exhibit 3). Notwithstanding its image as a leader in luxury auto manufacturing, Aston Martin continued to struggle financially. In May 2013, Bez announced that he would retire the following year. His departure created further turmoil for a company that seemed to lack direction and had already seen 2012 production fall to 3,574 units from a 2007 peak of 7,281. (See Exhibit 4.) Andy Palmer at Aston Martin In October 2014, Palmer stepped into the role of CEO. It was a homecoming for Palmer, who had grown up in nearby Stratford-upon-Avon and attended the University of Warwick and the University of Coventry, just miles from Aston Martin’s current Gaydon headquarters. “Owning an Aston Martin was a childhood dream,” he said. Palmer channeled his passion for cars into his career, earning graduate degrees in both product engineering and engineering management. He built a 23-year career at Nissan—including most recently a 13-year stint working and living with his family in Japan—where he rose to become chief planning officer (co-chief operating officer). But he always kept an eye on Aston Martin and, when offered, leapt at the opportunity to return to his native region and lead the iconic automaker. “All the stars aligned,” he said. “I felt a sense of duty to see if I could help turn the company around. Aston Martin is one of the only classic British car companies left.” By 2016, Aston Martin’s lineup of consumer models consisted mostly of two-door coupes and roadsters, including the street-friendly DB11 sports car grand tourer (GT), the V8 and V12 Vantage variants, the sportier Vanquish, and the Rapide four-door luxury sedan. Aston Martin also marketed some models under the Lagonda marque that had been revived in 2015 with the introduction of the Lagonda Taraf sedan, the first new Lagonda since the brand had been discontinued 1989. Aston Martin was one of the world’s most respected luxury brands. “We are more than a car company. We’re a true luxury company,” said Sproule. Aston Martin planned to open a shop at No. 8 Dover Street in London’s exclusive Mayfair district, offering luxury products such as clothing, eyewear, and textiles in collaboration with fashionable leading designers such as Hackett London, Marma London, Emilia Burano, Silver Cross, and FPM.24 The storefront would host events and classes, while also serving as an art exhibition space.25 Shoppers would be able to customize an Aston Martin vehicle, or even a 37-foot AM37 powerboat by Quintessence Yachts.26 “Our brand sits comfortably next to Jimmy Choo, Burberry, Hermès, and Patek Philippe,” Palmer said. “We don’t compete with the more than 80 million cars sold worldwide. Our customers want to show their identity and good taste.” He estimated that a group of 50,000 to 100,000 UHNW individuals and auto aficionados purchased a total of around 40,000 luxury vehicles annually. Among that set, Aston Martin was known as a leader in automotive design and engineering that lived up to the company’s mission, “For the Love of Beautiful.” Design & Engineering When Palmer arrived in 2014, notwithstanding the long gap since the DB9’s release, Aston Martin was still a leader in body design and engineering. The company was expert at material sciences, 5 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. 617-033 Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury crafting beautiful, lightweight bodies using aluminum, composites, carbon fiber, sheet molding, and other compounds. “Our unique know-how is in the bonded aluminum body structure. We lead the world in that,” said VP and Chief Special Operations Officer David King. Like many automakers, Aston Martin assembled its vehicles largely out of modular components acquired from tier-one suppliers or other auto manufacturers. “We can buy batteries, electrical systems, computers, even engines, but there are some parts you can’t buy off the shelf,” said King, referring to the body. Treating aluminum components with epoxy adhesives and chemical processes created super-strong bonds, which were so sturdy that the aluminum itself would tear before the bonds holding together the pieces of the body broke apart. The same technology was used in aerospace design due to its light weight and durability. Consumers had the opportunity to customize virtually every feature of their individual vehicles, from the specifics of the mechanical systems to the most detailed design features. Beginning with a particular model and variant—for example, either the V8 or V12 Vantage—customers used proprietary software at local dealerships to start the process of designing their own unique Aston Martin. “We have an online, highly graphical configurator that lets customers select the model and derivative they want, then specific features,” said Head of Information Technology (IT) Neil Jarvis. Dealers then communicated customer specifications to Gaydon. Most of the production process at the Gaydon facility were done by hand. Each vehicle took 220 hours to assemble, compared to about 20 hours per unit to build standardized premium vehicles, such as a top-end Land Rover. The only robot in the entire factory was the bonder, the machine used to perform the aluminum bonding process, which employees called “James,” as in, “Bonder. James Bonder.” Painting alone could take up to 80 hours. Customers frequently visited Gaydon in person to see their vehicle in various phases of production and to finalize details, such as paint and upholstery colors, accent materials, interior design, and myriad accessory options. One customer, a collector who had purchased multiple generations of Aston Martin vehicles, even commissioned a unique and exclusive paint color, which Aston Martin trademarked and used only for that customer’s vehicles. At full capacity, the Gaydon factory could produce 7,000 vehicles per year.27 In Need of a Tune-up Despite its strengths, Aston Martin suffered from weak earnings and organizational malaise when Palmer came on (see Exhibit 5). “We skipped a generation after DB9,” said CFO Mark Wilson. “Show me another car company that hasn’t fundamentally done a new product in a decade, and I’ll show you a dead car company.” “The £500 million or so [approximately $785 million] ownership budgeted in 2012 was supposed to deliver capital for designing new products, but it was being consumed on underperformance because the company wasn’t getting EBITDA in,” Palmer explained. “The money was used to cover operating costs rather than being put toward vehicle development.” There were also organizational problems. “Unfortunately, Aston Martin was careless about headcount,” said Chief Human Resources Officer and VP Michael Kerr. “We had a lot of redundancies. There were no constraints on corporate culture, and there were a lot of siloes and politics in the organization.” Early on, Palmer spearheaded organizational changes. “A cultural shift was needed,” Wilson said. “The company needed to give people the license to operate—not only to use data and their intuitions— but to set the stone in motion.” “Working hours here were not long,” he continued. “People went home mid-day on a Friday. Where were all the people with their hair on fire and bloodshot eyes?” Although painful, personnel cuts were deemed necessary. In 2014-2015, Aston Martin reduced 295 positions, going from roughly 2,100 to 1,800 employees. Remaining employees, including about 1,100 in manufacturing, saw a 12-month pay freeze, which Aston Martin negotiated with the unions. 6 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury 617-033 Management was trimmed to reduce bureaucracy and flatten the organizational structure. Three axes reported to the CEO: planning, functions, and regions. Planning included development of new products, from conceptualization and design through engineering. Functions included production, as well as marketing, finance, IT, and others. The six regions—China, Asia-Pacific, Europe, the U.K., the Americas, and Asia-Middle East-Africa—represented consumers and were charged with marketing and sales planning in their respective geographies. In all, the reorganization trimmed around £10 million ($15 million) in fixed costs from the annual budget and was expected to produce an additional £5 million (about $7 million) in cost reductions through efficiency improvements. Palmer hoped the new organizational structure would boost interactions across divisions, improve efficiency by reducing management layers, and promote transparency. Increasing collaboration between design and engineering was especially important, so Palmer appointed vehicle line executives (VLEs) to oversee each new development project. “Developing a high-end luxury car involves 300 to 400 production processes, so we need efficient management of those processes,” he said. Restarting the Engine: The Second Century Plan As it entered its second hundred years, Palmer sought to generate excitement about Aston Martin’s future. “Our challenge was to inject precision and a sense of purpose,” Wilson said. “We needed to articulate what’s important, and the Second Century Plan was the initial articulation.” In particular, the Second Century Plan called for refreshing Aston Martin’s lineup with new designs and upping production volume to increase earnings. The question was how to do it in a way that built on the automaker’s history of luxury while capitalizing on its traditional strengths in design and engineering. One path would be to follow the example of rival Ferrari by remaining a pure-play luxury sports car company. Ferrari, under former Chairman Luca Cordero di Montezemolo, had capped production at 7,000 units annually in an effort to avoid eroding its appeal as a “symbol of rarefied luxury.”28 To boost revenue, it produced and sold engines to sister-brand Maserati, owned by former Ferrari parent company Fiat, and licensed its brand for auto accessories, apparel, and souvenirs, which contributed $68 million in revenue during 2012.29 In 2014, Ferrari brought in $3.9 billion in revenue30 and was named the “world’s most powerful brand” by Brand Finance.31 In 2015, it put 10% of its equity on the New York Stock Exchange, and the IPO resulted in an $11 billion valuation. New Chairman and CEO Sergio Marchionne placed a greater emphasis on driving sales, including by increasing sports car production and possibly by broadening into more vehicle segments. However, some observers worried that the company risked accelerating growth at the expense of its unique identity and brand position.32 Another possibility was to remain committed to sports cars but move down market into the premium segment. Decreasing price and increasing volume could boost earnings but risked squandering Aston Martin’s hard-earned reputation for glamor, power, and class. Historically, the company had carefully tended its exclusivity. A good example was 2015’s DB10. The latest James Bond installment, Spectre—whose premiere Aston Martin executives had attended at London’s Royal Albert Hall—portrayed Agent 007 driving an Aston Martin DB10 outfitted with a flame-thrower and ejectorseat. Only 10 units of the DB10 were built, and, in February 2016, one was auctioned off at Christie’s for $3.5 million.33 In addition, 100 DB9 special edition James Bond tribute cars were produced. Palmer and his team ultimately settled on a third option: to remain in the luxury segment while broadening Aston Martin’s product portfolio to include vehicles beyond sports cars. The Second Century Plan aimed to develop a new sports car platform and boost sports car sales to 7,000 to 10,000 units annually within five years. It also called for developing vehicles in two new segments: a crossover SUV, called the DBX, and a new electric luxury sedan, the RapidE EV. In order to increase capacity, the 7 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. 617-033 Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury Second Century Plan also called for an $80 million investment in a new factory in Wales. Palmer had considered locating the new facility in the U.S. state of Alabama, where the government had proffered incentives to lure the company, but eventually opted to keep production in the U.K. “It’s a question of brand,” said Palmer. “It’s important to be made in the U.K. If we built in Alabama, would our cars still reflect the same bespoke, ‘crafted in U.K.’ quality? Bentley and Rolls-Royce aren’t made in the U.K., if we’re honest. They arrive from Germany and get finished up here.” By 2020, the Second Century Plan aimed to raise production to around 15,000 vehicles annually, with projected EBITDA of £500 million. New Vehicles DBX Aston Martin aimed to launch the DBX by 2019, targeting 5,000 units annually and a per unit price of £150,000 to £200,000. The decision to move ahead with DBX rested in large part on consumer trends. “The market is moving toward crossovers,” said VP and Chief Planning Officer Nick Lines. “People like the all-wheel drive, better traction, and command seat, where they can sit high up and feel more in control than in a sports car. Consumers want an automobile with more utility than our sports cars, and a big part of that is more space for passengers.” The DBX could potentially help to broaden Aston Martin’s customer base, particularly with women. “Historically, Aston Martin has only had about 3,000 female purchasers total,” said Karen Gibson, director, product planning. “For some women, our sports cars can seem like they’d be hard to drive, and that might turn off some of the female population. But in our target market of high net worth individuals, there is a high proportion of women and they influence many of the purchasing decisions. Data show that a luxury crossover SUV like the DBX will have a global market including women.” Gibson was assembling a HNW female advisory board to spur customer-driven product development. An open question was whether Aston Martin should develop an aluminum-based platform for the DBX from scratch—filling in various elements with components from Daimler and tier-one suppliers— or leverage its relationship with Daimler to use an existing pressed-steel platform from MercedesBenz’s luxury full-size SUV, the GL. Few other luxury crossover SUVs were on the market, but the DBX would face competition from full-size SUVs such as the Mercedes Benz’s GL-Class and GLS-Class (a combined 27,000 were sold in 2014 from around $65,000),34 the Porsche Cayenne (66,000 produced in 2014, starting at around $58,000,)35 and Land Rover’s Land and Range Rover models (385,000 sold in 2014 starting at around $85,000),36 among others. By 2016, Bentley had launched its own luxury SUV, the Bentayga, and Lamborghini intended to launch its Urus by 2018. RapidE EV Several members of the management team felt that customers had not responded to the Rapide four-door since its launch in 2010. “The Rapide sells in relatively strong numbers, but it hasn’t lived up to its full potential,” said Gibson, pointing out that just 200 to 300 units of the car sold each year in China, an important market for luxury sedans. “The Rapide is more of a four-door sports car than a true sedan,” said Lines, articulating one of the vehicle’s perceived shortcomings. Rather than scrapping the luxury sedan entirely, the Second Century Plan opted to keep it as a test platform for incorporating an electric engine. When it went to market in 2018, the RapidE EV would be the only luxury electric vehicle on the market. Palmer considered Tesla’s Model S, priced starting at around $69,000, to sit in the premium segment, and its $35,000 Model 3 was aimed at the mass market. A 0EV could also counter the heavy emissions from Aston Martin’s V8 and V12 engine models, helping the company’s overall product portfolio stay in compliance with CAFE standards. “At our current volume, we receive exemptions from emissions standards, which are intended to promote innovation and variety in the market,” said VP and General Counsel Michael Marecki. “Once we pass 10,000 total units across our portfolio, there are heavy taxes under CAFE and other regulatory regimes for 8 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury 617-033 exceeding overall emissions limits. A 0EV offering helps us stay under the limit.” Aston Martin aimed to sell around 1,500 units annually at a unit price of more than £200,000. Producing its own electric engines would require substantial investments in research and development (R&D) and new capabilities, so Aston Martin was considering whether to acquire engines from Daimler or another supplier. Another question was how to introduce an electric engine, which could confuse the brand and create a different driving experience from what its consumers had come to expect. The driver would be able to accelerate much faster than with a combustion engine and would feel more torque, but an electric engine would not produce the signature “growl” that an Aston Martin V8 or V12 emitted on startup, as Marecki put it. “People want more acceleration, which means more torque,” said King. “It’s sexy. Electrification is loads of torque, but you lose the crescendo people expect as they accelerate above 4,500 RPM [an engine’s revolutions per minute] because it happens instantly.” For each of the upcoming models, including future variants of the DB11, Aston Martin was also considering how best to make use of emerging trends around self-driving capabilities and Internetconnected vehicles. Again, driving experience was a major factor. “People don’t buy an Aston Martin sports car so that a computer can drive,” said Palmer. “We have to be careful how we use it.” Rather than a fully automated driving experience like the Google car, Palmer pointed to the possibility of automatic parking—increasing convenience and minimizing the chances of scratching a hubcap—and more radical possibilities, like a feature that allowed drivers to drift around corners on a racing track like professional drivers. Internet-connected features also could improve safety, as well as provide navigation, information, and entertainment options. However, “As far as digitizing the car, we need to understand what a connected Aston Martin is and means to customers,” said Jarvis. “Many will only once show their friends they can check their tire pressure from their phone.” The Right Approach? By 2016, even in the afterglow of the excitement of the DB11 premiere at the Geneva Motor Show, Palmer worried whether Aston Martin’s upcoming expansion into new product categories, its dramatic overall increase in production volume, and the planned incorporation of so much new technology into new platforms was the right strategy. It was hard to argue with the results of competitor Ferrari’s decision to remain a pure-play sports car company that derived extra revenue from its racing program and brand licensing—the company’s recent IPO brought them a 10x to 13x EBITDA valuation. “We look like Ferrari, but our scope is double if we do DBX—it’s the biggest game changer,” said Palmer. “Ferrari doesn’t have a crossover. If we get DBX right, other brand extensions come easier, including the RapidE EV and racing vehicles.” Was selling 14,000 units per year, about half of which would be in segments other than the company’s traditional heart and soul as a maker of high-performance luxury sports cars, the right approach? Would it dilute the exclusive brand image of Aston Martin? How should a high-end premium provider in any business grow without losing its exclusive reputation? 9 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. 617-033 Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury Exhibit 1 Leading Automakers and Production Volume, 2014 Manufacturer Cars Toyota Volkswagen 8,788,018 9,766,293 General Motors Hyundai Ford Nissan Fiat 6,643,030 7,628,779 3,230,842 4,279,030 1,904,618 Honda 4,478,123 Source: Representative Brands (Target Segment) Scion (entry); Toyota (mass); Lexus (premium); ŠKODA, Volkswagen (entry and mass); Audi, Porsche (premium); Bentley, Bugatti, Lamborghini (luxury) GMC, Chevrolet, Opel (entry and mass); Cadillac, Buick (premium) Kia (entry); Hyundai (mass); Genesis (premium) Ford (mass); Lincoln (premium) Datsun (entry); Nissan (mass); Inifiniti (premium); Nismo (luxury, sports) Fiat, Chrysler, Alfa Romeo, Dodge, Ram (entry and mass); Maserati, Jeep (premium) Honda (mass); Acura (premium) Adapted by casewriter from OICA Correspondents Survey, “World Motor Vehicle Production,” World Ranking of Manufacturers, 2014, http://www.oica.net/wp-content/uploads//Ranking-2014-Q4-Rev.-22-July.pdf, accessed November 2015. Exhibit 2 Aston Martin Overall Production Volume, in Number of Units, 1948-2015 ASTON MARTIN PRODUCTION: 1948 - 2015 8000 7000 6000 5000 4000 3000 2000 1000 0 1948 Source: 1958 1968 1978 1988 1998 2008 2018 Company documents. 10 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury Exhibit 3 617-033 Aston Martin Models in James Bond Films, 1964-2015 Goldfinger DB5, 1964 Thunderball DB5, 1965 On Her Majesty’s Secret Service DBS, 1969 The Living Daylights V8 Vantage, 1987 Goldeneye DB5, 1995 Die Another Day V12 Vanquish, 2002 Casino Royale V12 DBS, 2006 Casino Royale DB5, 2006 Quantum of Solace V12 DBS, 2008 Skyfall DB5, 2012 Spectre DB10, 2015 Spectre Premiere Royal Albert Hall, 2015 Source: Adapted by casewriter from company documents. Exhibit 4 Aston Martin Wholesale Volumes, 2005-2015 Model DB9 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 3,513 2,494 2,420 1,966 719 539 902 795 796 709 755 508 4,199 4,667 3,268 1,432 1,456 1,578 1,442 1,196 1,567 1,383 DBS / New Vanquish - - - 849 977 751 512 621 972 783 723 Rapide - - - - - 1,410 873 655 812 602 641 Sub-Total Core Volume 4,021 6,693 7,087 6,083 3,128 4,156 3,865 3,513 3,776 3,661 3,502 Special Projects 395 310 194 5 3 - 52 61 28 1 113 4,416 7,003 7,281 6,088 3,131 4,156 3,917 3,574 3,804 3,662 3,615 Vantage Total Wholesale Volume Source: Company documents. 11 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. 617-033 Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury Exhibit 5 Aston Martin Financials, 2009-2015 Income Statement (£ millions) 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Total Volumes 3,131 4,156 3,917 3,574 3,804 3,662 3,615 Net Revenue £ 348 £ 474 £ 507 £ 461 £ 519 £ 468 £510 Average Selling Price Per Unit (£ thousands) Cost of Sales (COS) £ 100 £ 104 £ 104 £ 108 £ 126 £ 114 £ 116 £ (228) £ (315) £ (334) £ (313) £ (352) £ (313) £ (345) Contribution £ 120 £ 159 £ 173 £ 148 £ 167 £ 155 £ 165 Fixed Costs & Other £ (62) £ (66) £ (97) £ (79) £ (82) £ (69) £ (94) £ 58 £ 93 £ 76 £ 69 £ 85 £ 66 £ 71 £ (36) £ (62) £ (63) £ (75) £ (71) £ (80) £ (119) £ 21 £ 31 £ 13 £ (6) £ 14 £ (14) £ (48) £3 £4 £ (5) £ (3) £ (12) £ (4) £ (10) £ (13) £ (28) £ (42) £ (27) £ (27) £ (53) £ (70) Profit Before Tax £ 12 £7 £ (33) £ (36) £ (25) £ (71) £ (128) Balance Sheet (£ millions) 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 £ 653 £ 683 £690 £ 719 £ 754 £ 800 £ 843 Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization (EBITDA) Depreciation and Amortization (D&A) EBIT Nonrecurring Items Finance Income/Expense Non-Current Assets Working Capital £4 £ (16) £ (33) £ (70) £ (20) £ (10) £ (28) £ (125) £ (144) £ (121) £ (91) £ (74) £ (88) £ (58) Total £ 532 £ 523 £ 536 £ 558 £ 659 £ 702 £ 757 Cash £ (39) £ (43) £ (47) £ (50) £ (75) £ (89) £ (66) Previous Borrowings £ 229 £ 236 - - - - - Senior Secured - - £ 304 £ 304 £304 £ 304 £ 304 Payment in Kind - - - - - £ 114 £ 138 Preference Shares - - - - - Short Term Debt - - - £ 41 £ 14 £ 20 £ 17 Net Debt £ 190 £ 191 £ 257 £ 295 £ 243 £ 349 £ 493 Shareholders’ Funds £ 342 £ 333 £ 279 £ 263 £ 416 £ 353 £ 264 Total £ 532 £ 523 £ 536 £ 558 £ 659 £ 702 £ 757 Other Assets (Liabilities) Source: £ 100 Company documents. 12 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury 617-033 Appendix A: Auto Industry China, Japan, Germany, and the U.S. were the top auto-producing countries.37 The largest manufacturer was Toyota, at over 10 million cars, commercial vehicles, and buses per year, followed by Volkswagen, General Motors, Hyundai, Ford, Nissan, Fiat Chrysler Automobiles, and Honda. In 2015, global industry sales of passenger cars, sport utility vehicles, light and heavy trucks, buses, and specialty and recreational vehicles were $8.7 trillion.38 Manufacturers recognized revenues when vehicles shipped to dealers. From 2010 to 2015, worldwide industry revenues grew at an annualized growth rate of 2.4% and were forecast to climb to $9.4 trillion by 2020.39 Passenger vehicles accounted for 70% of industry revenues and were divided into the car-and-SUV segment and the pick-up truck segment (information in the following paragraphs is from.40 Cars, the most common type of vehicle, included sedan or hatchback models and typically were more fuelefficient than pick-up trucks or SUVs. In 2016, demand for fuel-efficient vehicles was rising, and crossover utility vehicles, which attempted to combine the fuel efficiency of cars with the driving feel of SUVs, were emerging as a popular segment. Sales across all vehicle segments were growing fastest in developing and so-called BRIC nations (Brazil, Russia, India, and China), in part due to higher disposable incomes and increased investments in road networks. In 2014, China for the first time surpassed the U.S. in worldwide market share of passenger vehicle sales, taking over the top rank with 30.3% of worldwide passenger vehicle sales, up from 24.8% in 2010.41 Populations in some developed economies, particularly in Europe, were increasingly turning to alternative modes of transportation rather than replacing old vehicles with new models. In Japan and several other countries, younger populations were less interested in owning a vehicle. Manufacturers depended on a highly fragmented market of dealerships to drive sales. Dealerships were most highly concentrated in China, the U.S., Japan, Germany, and France. Body style, engine size, color, and, increasingly, fuel efficiency, played a role in consumer decisions when selecting a car. From 2010 to 2015, Internet-based sales strategies had become more important for dealers and manufacturers alike, as consumers gathered information independently online before purchasing a new vehicle. Dealers sought to collaborate with online outlets to drive traffic to their dealerships. Product and service mix also affected profit margins, as dealers offering parts and repair services garnered higher margins. In general, competition in the dealership industry was driven by price, service, and product range, and consumers demonstrated a willingness to pay a premium for better service. 13 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. 617-033 Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury Appendix B: Luxury Brands in the Auto Industry and Beyond Ferrari Based in Maranello, Italy, Ferrari had been founded in 1969. For much of its history it was owned by Fiat. In 2014, the company brought in $3.9 billion in revenue and earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) of $540 million.42 In October 2015, Ferrari put 10% of its equity on the New York Stock Exchange. The initial public offering (IPO) was a success, with shares priced at $52 each for an enterprise value of $11 billion, although observers pegged its brand value at $4 billion, 350th on Brand Finance’s 2014 Global 500 index.43 Of the IPO, one observer wrote, “As a small auto firm, Ferrari ought to trade on the stock-market with a price/earnings (p/e) ratio of around the sector’s average of 13 or so. However, opening as it did at $52 a share, the appetite for the company’s stock implied a p/e three times greater. That is the upper end of the luxury-goods market.”44 Following the IPO, Fiat retained 80% ownership of the company, while Piero Ferrari, the son of the company’s founder, owned 10%.45 Leading up to the IPO, Ferrari worried that rising production volume might erode its brand appeal as a “symbol of rarefied luxury.”46 In 2012, the brand sold 7,318 cars, and it planned to reduce production to 7,000 units the following year.47 Ferrari had 3,000 employees in 2013 working to produce its five V8 and V12 cars at a rate of 32 cars per day.48 It created licensed merchandise, such as apparel, auto accessories, and souvenirs that in 2012 contributed $68 million in revenue,49 and also produced limited edition cars such as the La Ferrari hybrid, which sold out its 499 units following its debut at the Geneva Motor Show, and had a program with the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile’s Formula 1, the highest-class of professional auto racing in the world.50 Ferrari also generated revenue through production and sales of engines to sister-brand Maserati, also owned by parent company Fiat, and had invested in a $52 billion plant and 100 to 200 workers for that purpose.51 The company planned to invest an additional $130 million over 2013 to 2015 in new facilities.52 Maserati launched two new higher-margin vehicles, the Quattroporte and the Ghibli.53 Top Ferrari sales markets included the U.S., China, Germany, and Britain. Europe and the Middle East combined accounted for 52% of revenues in 2013, with the U.S. following at 20%, and Asian markets with 30%.54 Chairman Luca Montezemolo announced the brand’s intention to shift sales to 30% U.S., 30% Asia, and 40% Europe and the Middle East by 2017.55 At the same time, Montezemolo denied that Ferrari would ever reduce the size of its cars or produce a 100% electric car.56 By 2016, Fiat distributed its remaining stake to public shareholders and relinquished ownership of Ferrari.57 Jaguar Land Rover In 1922, Jaguar began by manufacturing motorcycle sidecars and, following WWII, high-end saloons and sports cars. In the 1950s, Jaguar vehicles won a number of prominent motorsports events, adding to the company’s reputation for excellent sports cars, including the famous E-type. In 1968, Jaguar became a part of British Leyland, which also owned the Land Rover brand of all-terrain vehicles manufactured for the military. In 1970, Rover launched the Range Rover brand to sell its off-road vehicles to recreational consumers. In 1989, Ford acquired Jaguar and in 2000 purchased Land Rover and its Range Rover brand. Ford put the two auto brands in its Premier Automotive Group along with Aston Martin and Volvo. The two brands were tightly integrated, operating as Jaguar and Land Rover (JLR) and sharing management, components, and production facilities across the street from Aston’s headquarters in Warwickshire. By 2008, shortly after having sold Aston, Ford also sold off Jaguar and Land Rover, which were bought by the Indian automaker Tata Motors for $2.3 billion.58 The sale of the two auto makers to different owners brought an end to the sharing of facilities near Gaydon, including the automotive test track, and contributed to subsequent tensions as the two companies competed for talent and local resources.59 Bentley In 1919, W.O. Bentley started Bentley Motors in London, England to manufacture highperformance, handmade luxury cars. Bentley’s reputation as a maker of top-quality grand tourers was 14 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury 617-033 cemented with wins in the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the France’s famed sports car endurance race, in 1924, 1927-1930. In 1988, Volkswagen acquired Bentley, which by then was headquartered in Crewe, England. In 2003, Bentley’again won at Le Mans, reclaiming some of its past racing glory. By the twenty-first century, Bentley offered three main lines of well-known luxury sedans: the Continental, the Flying Spur, and the Mulsanne. In 2012, Bentley introduced a controversial new vehicle at the Geneva Motor Show, the EXP 9 F concept SUV. The SUV’s design was panned in the press, but Bentley's COO explained, “Most of our customers have an SUV, and are asking us to make one because they cannot move up from what they have.”60 The following year, Bentley sold 10,120 units, 25% of all new luxury cars worldwide.61 Jimmy Choo Jimmy Choo was a luxury shoe brand that specialized in high-end stilettos and Italian craftsmanship.62 Co-founders Tamara Mellon and Malaysian cobbler Jimmy Choo met in the early 1990’s when Mellon, in her role as accessories editor at British Vogue, contracted with Choo to create shoes for photo shoots.63 When Mellon lost her job at the magazine, she enlisted her father, who had co-founded the Vidal Sassoon hair products company, to fund her new shoe brand. In 1996, the first Jimmy Choo store was opened on Motcomb Street in London,64 and the first U.S. store opened in New York City in 1998, followed by Los Angeles in 1999.65 At first, Choo owned half the company, but in 2001 he was bought out by a private equity firm for $13 million. The company’s valuation grew from $29 million in 2001 to nearly $900 million in 2011, when private equity firm Labelux bought the company.66 In October 2014, the company went public.67 Early on, Princess Diana was a client.68 The brand became a household name, thanks in part to celebrity endorsements from the cable television sitcom Sex and the City,69 singer Beyoncé—who sang about “kicking it in my Jimmys”—First Lady Michelle Obama, actress Meryl Streep, and singer Madonna.70 Manufacturing of the handmade stilettos took four months. Shoes were assembled in Italian factories.71 Recently, sales had soared in Asia. Burberry Burberry was a luxury clothing and accessories company known for its trademark In 1856, Thomas Burberry opened a men’s outerwear store in Basingstoke, England. In 1879, he invented gabardine, “a firm, hard-finish durable fabric (as of wool or rayon) twilled with diagonal ribs on the right side,” which was tough, waterproof, and breathable.73,74,75 In 1891, Burberry opened its first London store and in 1909 it expanded to Paris, France.76 The brand was a favorite among adventurers, including Norwegian Explorer Roald Amundsen, who reached the South Pole while wearing Burberry clothing and toting a Burberry gabardine tent, and Claude Grahame-White, the first aviator to fly between London and Manchester, England in less than 24 hours. Between 1914 and 1917, British explorer Ernest Shackleton traveled to Antarctica wearing Burberry gabardine.77 During World War I, Burberry produced the first trench coat for use by army officers.78 By the late twentieth century, Burberry had expanded globally to offer products via wholesale, stores, and third-party retailers in markets including New York, Buenos Aires, Argentina, Montevideo, Uruguay, Japan, and throughout Asia and Europe. In 2002, Burberry was listed on the London Stock Exchange for the first time. In 2006, when Angela Ahrendts was brought on as CEO, the company was growing at 2% a year and offered a diverse product line. By the end of fiscal 2012, Burberry’s revenues had doubled over the previous five years to $600 million. In 2013, Ahrendts wrote, “In luxury, ubiquity will kill you—it means you’re not really luxury anymore. And we were becoming ubiquitous. Burberry needed to be more than a beloved old British company.”79 Under her direction, the company began to target younger consumers. plaid.72 Hermès Hermès International was a French maker of luxury goods, including leather accessories, personal items, and perfume. Established in 1837 and headquartered in Paris, the company was perhaps best known for its silk scarves and the Birkin handbag, a leather tote that ranged in price from more than $11,000 to $150,000 at retail. 15 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. 617-033 Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury Patek Philippe Swiss watchmaker Patek Philippe & Co., a Geneva-based privately-owned company established in 1851, designed and sold some of the world’s “most prized timepieces,” according to connoisseurs.80 The company employed approximately 1,300 people and produced around 40,000 watches annually. Watches sold for prices ranging from $10,000 to $11 million.81 Producing intricate, fine timepieces was an artisanal process that was difficult to automate or outsource.82 Patek Philippe watches were sold to luxury consumers in European and North American markets, as well as increasingly in Russia, China, and the Middle East. To convey prestige and exclusivity, the company created three salons, which were branded retail shops in London, England, Geneva, Switzerland, and Paris, France. Elsewhere, its watches were distributed via 500 authorized retailers, which the company carefully vetted. Limited production runs, along with limited-release designs and special collections, helped Patek Philippe maintain the brand’s aura of exclusivity. Much of the company’s brand equity and success was based on the impression among collectors and consumers that purchasing a Patek Philippe was an investment, as the watches’ value would appreciate over time. In fact, the company’s brand messaging stated, “You never actually own a Patek Philippe, you merely look after it for the next generation.” 16 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury 617-033 Endnotes 1 OICA 2015 Production Statistics, http://www.oica.net/category/production-statistics/, accessed March 2016. 2 Robert Wright, “GM and Ford face challenge to plot course to profitable growth,” Financial Times, October 2, 2014, http://on.ft.com/1CHb8nP, accessed November 2015. 3 Andy Sharman, “Premium carmakers see China drama ahead,” Financial Times, August 30, 2015, http://on.ft.com/1IvUcRp, accessed November 2015. 4 Sharman. 5 Grainne Gilmore, “UHNWI Population Growth Continues,” The Wealth Report, Knight Frank, 2015, http://www.knightfrank.com/wealthreport/2015/wealth-distribution/uhnwi-growth, accessed December 2015. 6 Gilmore. 7 Madelaine Ollivier, “Luxury Research,” The Wealth Report, Knight Frank, 2015, p. 62, http://www.knightfrank.com/ resources/wealthreport2015/wealthpdf/07-wealth-report-luxury-spending-chapter.pdf, accessed December 2015. 8 Ollivier. 9 Paul Gao, et al., “Disruptive Trends that will Transform the Auto Industry,” McKinsey, January 2016, http://www.mckinsey.com/industries/high-tech/our-insights/disruptive-trends-that-will-transform-the-autoindustry?cid=other-eml-alt-mip-mck-oth-1602, accessed February 2016. 10 “2015 Auto Industry Trends,” PricewaterhouseCoopers, January 2015, http://www.strategyand.pwc.com/perspectives/2015-auto-trends, accessed March 2016. 11 Robert Wright, “Luxury cars gain fuel-efficiency appeal,” Financial Times, April 7, 2015, http://on.ft.com/1H1cYnd, accessed November 2015. 12 Wright, “Luxury cars gain fuel-efficiency appeal.” 13 Boston Consulting Group, “What’s Ahead for Car Sharing,” BCG Perspectives, https://www.bcgperspectives.com/content/articles/automotive-whats-ahead-car-sharing-new-mobility-its-impact-vehiclesales/?chapter=8, accessed November 2016. 14 Boston Consulting Group, “What’s Ahead for Car Sharing.” 15 J. Philip Rathgen, “Cometh the Hour, Cometh the Man: Sir David Brown,” Classic Driver, May 10, 2013, https://www.classicdriver.com/en/article/classic-life/cometh-hour-cometh-man-sir-david-brown, accessed April 2016. 16 Rathgen. 17 Rathgen. 18 “Jaguar Land Rover: a history,” The Telegraph, February 11, 2010, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/ finance/newsbysector/transport/8163797/Jaguar-Land-Rover-a-history.html, accessed February 2016. 19 Nick Bunkley, “Ford Sells Aston Martin Unit,” The New York Times, March 12, 2007, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/12/business/worldbusiness/12iht-ford.4881210.html?_r=0, accessed January 2016. 20 Alex Webb and Jacqueline Simmons, “Investindustrial to Purchase 37.5% Stake in Aston Martin,” Bloomberg Business, December 7, 2012, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2012-12-07/investindustrial-to-purchase-37-5-stake-in-astonmartin, accessed January 2016. 21 Richard Holt, “Aston Martin Signs Engine Deal with Mercedes-AMG,” Telegraph, December 19, 2013, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/luxury/motoring/19368/aston-martin-signs-engine-deal-with-mercedes-amg.html, accessed January 2016. 22 Holt. 23 “In-Vehicle Infotainment (IVI),” Webopedia, http://www.webopedia.com/TERM/I/in-vehicle-infotainment-ivi.html, accessed December 2015. 17 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. 617-033 Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury 24 “Aston Martin touts brand extensions, collaborations in immersive storefront,” Luxury Daily, September 1, 2016, https://www.luxurydaily.com/aston-martin-touts-brand-extensions-collaborations-in-immersive-storefront/, accessed November 2016. 25 “Aston Martin touts brand extensions . . ..” 26 Forrest Cardamenis, “Aston Martin moves beyond automobiles to showcase the Art of Living,” Luxury Daily, June 13, 2016, https://www.luxurydaily.com/aston-martin-moves-beyond-beautiful-cars-to-showcase-the-art-of-living/, accessed November 2016. 27 Peter Campbell, “Aston Martin doubles production capacity with £200m Welsh plant,” Financial Times, February 23, 2016, https://www.ft.com/content/e264aea2-da46-11e5-98fd-06d75973fe09, accessed November 2016. 28 The Telegraph, “Ferrari Tries To Cut Car Sales To Protect Brand Exclusivity,” May 8, 2013, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/transport/10044827/Ferrari-tries-to-cut-car-sales-to-protect-brandexclusivity.html, accessed October 2015. 29 The Telegraph, “Ferrari Tries To Cut . . ..” 30 Nicole Bullock and Andy Sharman, “Ferrari lines up luxury pit stops on high-octane IPO roadshow,” Financial Times, October 11, 2015, http://on.ft.com/1MpVaW9, accessed November 2015. 31 Robert Haigh, “Ferrari—The World’s Most Powerful Brand,” Brand Finance, 2014, http://brandfinance.com/news/ferrari-- the-worlds-most-powerful-brand/, accessed May 2016. 32 Dan Neil, “What Will Ferrari Be After Luca Cordero di Montezemolo Leaves?” The Wall Street Journal, September 19, 2014, http://www.wsj.com/articles/what-will-ferrari-be-after-luca-cordero-di-montezemolo-leaves-1411158289, accessed November 2016. 33 Kristen Lee, “James Bond’s Aston Martin DB10 Just Sold for $3.5 Million at Auction,” Road and Track, http://www.roadandtrack.com/car-culture/news/a28220/james-bonds-aston-martin-db10-just-sold-for-35-million-atauction/, accessed March 2016. 34 Timothy Cain, “Mercedes-Benz GL-Class/GLS-Class Sales Figures,” Good Car Bad Car, January 1, 2011, updated 2015, http://www.goodcarbadcar.net/2011/01/mercedes-benz-gl-class-sales-figures.html, accessed February 2016. 35 Porsche, 2014 Annual Report, http://www.porsche.com/international/aboutporsche/overview/dataandfacts/, accessed February 2016. 36 Alan Tovey, “Jaguar Land Rover is Back and Purring Again,” The Telegraph, September 19, 2015, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/11876795/Jaguar-Land-Rover-is-back-and-purring-again.html, accessed February 2016. 37 OICA 2015 Production Statistics. 38 Bertel Schmitt, “Nice Try VW: Toyota Again World’s Largest Automaker” Forbes, January 27, 2016, http://www.forbes.com/sites/bertelschmitt/2016/01/27/nice-try-vw-toyota-again-worlds-largestautomaker/#341b52412b65, accessed November 2015. 39 “Global Car & Automobile Sales,” via IBIS World, March 2015, pp. 6-19, accessed November 2015. 40 “Global Car & Automobile Sales.” 41 “Global Car & Automobile Sales.” 42 Bullock and Sharman. 43 “Ferrari changes its tune,” The Economist, November 9, 2015, http://www.economist.com/news/science-and-technology/ 21677625-famous-its-tenor-signature-italian-carmaker-learning-sing-soprano-ferrari-changes, accessed November 2015. 44 “Ferrari changes its tune.” 45 Automotive News, “Ferrari finally splits from Fiat-Chrysler,” Autoweek, January 4, 2016, http://autoweek.com/article/car- news/ferrari-finally-splits-fiat-chrysler, accessed February 2017. 46 The Telegraph, “Ferrari Tries To Cut Car Sales To Protect Brand Exclusivity.” 47 The Telegraph, “Ferrari Tries To Cut Car Sales To Protect Brand Exclusivity.” 18 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury 617-033 48 The Telegraph, “Ferrari Tries To Cut Car Sales To Protect Brand Exclusivity.” 49 The Telegraph, “Ferrari Tries To Cut Car Sales To Protect Brand Exclusivity.” 50 The Telegraph, “Ferrari Tries To Cut Car Sales To Protect Brand Exclusivity.” 51 The Telegraph, “Ferrari Tries To Cut Car Sales To Protect Brand Exclusivity.” 52 The Telegraph, “Ferrari Tries To Cut Car Sales To Protect Brand Exclusivity.” 53 The Telegraph, “Ferrari Tries To Cut Car Sales To Protect Brand Exclusivity.” 54 The Telegraph, “Ferrari Tries To Cut Car Sales To Protect Brand Exclusivity.” 55 The Telegraph, “Ferrari Tries To Cut Car Sales To Protect Brand Exclusivity.” 56 The Telegraph, “Ferrari Tries To Cut Car Sales To Protect Brand Exclusivity.” 57 “Ferrari finally splits from Fiat-Chrysler.” Automotive News, January 4, 2016, http://autoweek.com/article/car- news/ferrari-finally-splits-fiat-chrysler, accessed November 2016. 58 “Jaguar Land Rover: a history,” The Telegraph, February 11, 2010, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/ transport/8163797/Jaguar-Land-Rover-a-history.html, accessed February 2016. 59 Heather Timmons, “Ford Sells Land Rover and Jaguar to Tata,” The New York Times, March 26, 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/26/business/worldbusiness/26cnd-auto.html, accessed January 2016. 60 Nelson Ireson, “Bentley’s SUV, Next Flying Spur, & Moving Down-Market: Interview with Christohpe Georges,” Motor Authority, January 23, 2013, http://www.motorauthority.com/news/1081878_bentleys-suv-next-flying-spur-moving-downmarket-interview-with-christophe-georges, accessed March 2016. 61 Foxysteph, “Bentley Heads Off the Motoring track, Into Global Boardrooms,” Foxy Lady Drivers Club, January 26, 2014, https://www.foxyladydrivers.com/foxyblog/2014/01/26/bentley-heads-off-the-motoring-track-into-global-boardrooms/, accessed March 2016. 62 Christina Binkley, “How a Jimmy Choo Shoe Became a Global Best Seller,” Wall Street Journal, April 30, 2014, http://www.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304178104579533840140883978, accessed February 2016. 63 Susan Berfield, “Jimmy Choo Co-Founder Tamara Mellon Puts on Her Revenge Boots,” Bloomberg Business Week, October 4, 2013, http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/articles/2013-10-04/jimmy-choo-co-founder-tamara-mellon-puts-on-her-revengeboots, accessed February 2016. 64 Berfield. 65 Company Profile, from the Jimmy Choo website, http://us.jimmychoo.com/en/customer-services/about-us.html, accessed February 2016. 66 Berfield. 67 Company Profile, from the Jimmy Choo website. 68 Company Profile, from the Jimmy Choo website. 69 Jessica Bumpus, “Sandra Choi: The Great Shoe Challenge,” Vogue News, July 6, 2015, http://www.vogue.co.uk/news/2015/07/06/jimmy-choo-sandra-choi-interview, accessed February 2016. 70 James Thompson, “Jimmy Choo: The world's most valuable shoemaker,” The Independent, September 10, 2010, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/analysis-and-features/jimmy-choo-the-worlds-most-valuable-shoemaker2076499.html, accessed February 2016. 71 Binkley. 72 Cecilie Rohwedder, “Style & Substance: Playing Down the Plaid; Burberry's New CEO Seeks Alternate Brand Symbols as Famed Tartan Grows Trite,” Wall Street Journal, July 7, 2006, via ProQuest, accessed February 18, 2016). 73 Company History, from the Burberry website, http://www.burberryplc.com/about_burberry/company- history?WT.ac=Company+History, accessed February 2016. 19 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies. 617-033 Aston Martin: A Second Century of Performance and Luxury 74 “Gabardine,” Merriam Webster Online, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gabardine, accessed February 2016. 75 Christopher M. Moore and Grete Birtwistle, “The Burberry Business Model: Creating an International Luxury Fashion Brand,” International Journal of Retail &Distribution Management 32, no. 8, 2004, pp. 8, via ProQuest, accessed February 2016. 76 Moore and Birtwistle. 77 Company History, from the Burberry website. 78 Company History, from the Burberry website. 79 Angela Ahrendts, “Burberry’s CEO on Turning an Aging British Icon into a Global Luxury Brand,” Harvard Business Review, January-February 2013, https://hbr.org/2013/01/burberrys-ceo-on-turning-an-aging-british-icon-into-a-global-luxury-brand, accessed February 2016. 80 KPMG International, “Standing the Test of Time,” Consumer Currents, 2008, Issue 5, pp. 16, http://www.kpmg.com.cn/en/virtual_library/Consumer_markets/Consumer_Currents/CC0805.pdf, accessed February 2016. 81 Nishu Kakkar, “21 Most Expensive Patek Phillippe Watches,” The Most Expensive Journal, http://most- expensive.com/patek-philippe-watches, accessed February 2016. 82 KPMG International, “Standing the Test of Time,” pp. 17, http://bit.ly/1KBtL4w, accessed February 2016. 20 This document is authorized for use only by Rafael Vidal (rafaelvidal@tec.mx). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.