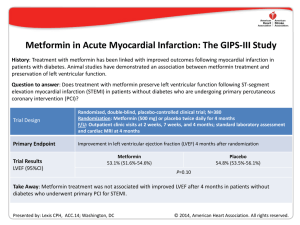

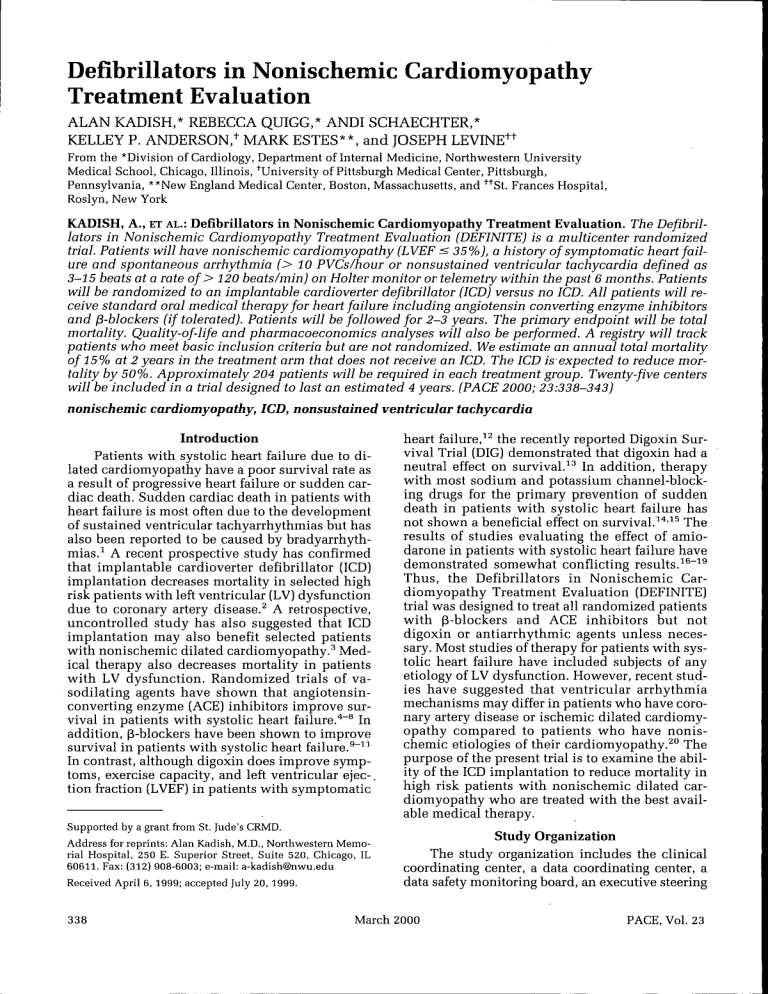

Defibrillators in Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation ALAN KADISH,* REBECCA QUICC,* ANDI SCHAECHTER,* KELLEY P. ANDERSON,^ MARK ESTES**, and JOSEPH LEVINE++ From the *Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago, Illinois, ^University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, **New England Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, and ''"''St. Frances Hospital, Roslyn, New York KADISH, A., ET AL.: Defibrillators in Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation. The Defibril- lators in Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation (DEFINITE) is a multicenter randomized trial. Patients will have nonischemic cardiomyopathy (LVEE < 35%), a history of symptomatic heart failure and spontaneous arrhythmia (> 10 PVCs/hour or nonsustained ventricular tachycardia defined as 3-15 beats at a rate of > 120 beats/min) on Holter monitor or telemetry within the past 6 months. Patients will be randomized to an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) versus no ICD. All patients will receive standard oral medical therapy for heart failure including angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and p-blockers (if tolerated). Patients will be followed for 2-3 years. The primary endpoint will be total mortality. Quality-of-life and pharmacoeconomics analyses will also be performed. A registry will track patients who meet basic inclusion criteria but are not randomized. We estimate an annual total mortality of 15% at 2 years in the treatment arm that does not receive an ICD. The ICD is expected to reduce mortality by 50%. Approximately 204 patients will be required in each treatment group. Twenty-five centers will be included in a trial designed to last an estimated 4 years. (PACE 2000; 23:338-343) nonischemic cardiomyopathy, ICD, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia Introduction Patients with systolic heart failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy have a poor survival rate as a result of progressive heart failure or sudden cardiac death. Sudden cardiac death in patients with heart failure is most often due to the development of sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias hut has also heen reported to he caused hy bradyarrhythmias.^ A recent prospective study has confirmed that implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) implantation decreases mortality in selected high risk patients with left ventricular (LV) dysfunction due to coronary artery disease.^ A retrospective, uncontrolled study has also suggested that ICD implantation may also benefit selected patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy.^ Medical therapy also decreases mortality in patients with LV dysfunction. Randomized trials of vasodilating agents have shown that angiotensinconverting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors improve survival in patients with systolic heart failure."*"^ In addition, (S-blockers have heen shown to improve survival in patients with systolic heart failure.^"^^ In contrast, although digoxin does improve symptoms, exercise capacity, and left ventricular ejec-. tion fraction (LVEF) in patients with symptomatic Supported by a grant from St. Jude's CRMD. Address for reprints: Alan Kadish, M.D., Northwestern Memorial Hospital, 250 E. Superior Street, Suite 520, Chicago, IL 60611. Fax: (312) 908-6003; e-mail: a-kadish@nwu.edu Received April 6, 1999; accepted July 20, 1999. 338 heart failure,^^ the recently reported Digoxin Survival Trial (DIC) demonstrated that digoxin had a neutral effect on survival.^^ In addition, therapy with most sodium and potassium channel-hlocking drugs for the primary prevention of sudden death in patients with systolic heart failure has not shown a beneficial effect on survival.^*'^^ The results of studies evaluating the effect of amiodarone in patients with systolic heart failure have demonstrated somewhat conflicting results.^^~^^ Thus, the Defibrillators in Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation (DEFINITE) trial was designed to treat all randomized patients with (B-blockers and ACE inhibitors but not digoxin or antiarrhythmic agents unless necessary. Most studies of therapy for patients with systolic heart failure have included suhjects of any etiology of LV dysfunction. However, recent studies have suggested that ventricular arrhythmia mechanisms may differ in patients who have coronary artery disease or ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy compared to patients who have nonischemic etiologies of their cardiomyopathy.^" The purpose of the present trial is to examine the ability of the ICD implantation to reduce mortality in high risk patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy who are treated with the best available medical therapy. Study Organization The study organization includes the clinical coordinating center, a data coordinating center, a data safety monitoring hoard, an executive steering March 2000 PACE, Vol. 23 DEFINITE committee, and the investigational sites (Appendix 1). A contracting organization, Ovations (Highland Park, IL), will perform cost analysis and quality-oflife analysis. In addition, the study will contain a three-memher supervisory committee not including the principal investigations at Northwestern University. All three members of the committee have extensive experience with multicenter clinical trials and grant peer review at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the American Heart Association (AHA). In the event that the data safety monitoring hoard has concerns regarding patient enrollment or patient safety or it recommends discontinuation of the study because of either a positive or negative endpoint, the final decision regarding study status will made by the independent supervisory committee at Northwestern University rather than the steering committee or the principal investigators. The study is funded by St. Jude's CRMD. The data safety monitoring board and. principal investigators have disclosed potential conflicts of interest based on the AHA and American College of Cardiology (ACC) guidelines. Trial Design Patients who meet inclusion criteria will be randomized to one of two treatment arms. 1. Standard oral medical therapy for heart failure including ACE inhihitors, 3-adrenergic blockers (if tolerated), and, if necessary, digoxin and diuretics to control sympyoms. 2. Oral medical therapy (as above) pins ICD implantation. No antiarrhythmic agents will be used in either treatment arm nnless indicated for the treatment of atrial fibrillation. Enrollment is projected to occur over 2 1/2 years with a postenroUment follow-up of 1 1/2 years. Patient Population Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the main trial are shown in Table I. Basic inclusion criteria inclnded an ejection fraction < 0.36 and the presence of ambient arrhythmias and nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. A history of symptomatic heart failure is also reqnired for inclusion in the study. If the ejection fraction is estimated to be between 0.30 and 0.35 by echocardiogram or biplane cardiac catheterization, radionuclide angiography is required to confirm the ejection fraction. The presence of a single episode of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia on telemetry monitoring is acceptable for study inclnsion. An average of s 10 premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) per hour or nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (3-15 beats at a rate of > 120 beats/min) on 24-hour Holter monitoring or telemetry monitoring is also acceptable for inclusion in the study. This arrhyth- Table I. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria Inclusion Criteria 1. Age 21-80 years 2. Nonischemic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 35% by any technique including radionuclide angiography (MUGA), echocardiogram or left ventriculogram 3. History of symptomatic heart failure 4. Documented nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT, 3-15 beats) or > 10 premature ventricular contractions (PVCS) per hour (or both) on Holter monitor or telemetry within the past 6 months. 5. Excluding coronary artery disease by the absence of a history of a Q wave myocardial infarction and a. coronary angiography demonstrating > 50% proximal or > 75% distal luminal stenosis in one or more of the main coronary arteries, or b. stress testing with nuclear perfusion imaging or dobutamine echocardiography demonstrating any evidence of ischemia Exclusion Criteria 1. Symptomatic ventricular arrhythmias 2. Unexplained syncope within the past 6 months 3. Prior cardiac arrest, sustained ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation 4. New York Heart Association Class IV heart failure at the time of enrollment 5. Familial cardiomyopathy associated with sudden death, hypertrophic or restrictive cardiomyopathy, constrictive pericarditis, clinically acute myocarditis or congenital heart disease 6. Permanent pacemaker 7. Electrophysiology study within the past 3 months 8. Patients in whom cardiac transplantation appears to be imminent or patients expected to undergo other cardiac surgery within 1 year PACE, Vol. 23 March 2000 339 KADISH, ET AL. mia marker was selected primarily based on the Argentinean Cooperative (GESICA) trial, which suggested that the presence of this arrhythmia marker conferred a relative risk of total mortality of 1.6-2.5 in patients with a nonischemic cardiomyopathy.^^ However since the trial was initiated, other studies have not consistently confirmed this observation.^^'^^ The absence of significant coronary artery disease as the etiology of the cardiomyopathy will be confirmed by coronary angiography or by a negative stress imaging study. Some patients with a nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy may have minimal coronary artery disease that is felt to be unrelated to the primary etiology of heart failure and, therefore, prognosis. Thus, the presence of a proximal lesion < 50% or a distal lesion in one of the main coronary arteries < 75% will not exclude participation in the study. Small branch occlusions will also not constitute exclusion criteria. Patients with severe symptomatic Class IV congestive heart failure or patients who are not candidates for ICD implantation will be excluded from the study. Patients with recent unexplained syncope may have a significant adverse prognosis and thus will not be included in the study. In addition, patients who have undergone electrophysiologicai testing within the last 3 months and patients with permanent pacemakers will also be excluded. dition, p-blocker therapy is required unless there is demonstrated patient intolerance. An attempt will be made to slowly titrate the ACE inhibitor and p-blockers to the highest tolerated dose. We expect to achieve a > 75% treatment rate with pblockers and ACE inhibitors, Digoxin and diuretics may be used when necessary to manage clinical symptoms. To avoid confounding factors that may decrease the study power, antiarrhythmic drug use is discouraged in the trial. However, it is recognized that some patients with LV dysfunction may have symptomatic atrial fibrillation or supraventricular arrhythmias requiring treatment and will not constitute an exclusion criteria. Any patient receiving antiarrhythmic drugs for ventricular arrhythmia will be excluded at the time of randomization and the use of any antiarrhythmic drug including amiodarone during follow-up will require approval of the principal investigators. Randomization Patients will be randomized into two treatment groups in an unblinded fashion. Randomization will be stratified by center and for the use of antiarrhythmic drugs for supraventricular arrhythmias at the time of randomization. Randomization will be performed centrally and randomization status will be assigned to investigational sites only after patients have given signed consent and inclusion criteria are confirmed, Drug Therapy and Antiarrh)rthmic Drug Use All patients will receive ACE inhibitors unless contraindicated. If patients are unable to tolerate ACE inhibitors, hydralazine and nitrates as a second level vasodilator therapy may be substituted. Angiotensin II converting enzyme blocking agents may be used at the investigator's discretion in drug intolerant patients; however, because randomized studies demonstrating prognostic benefit are not yet convincing, they are to be reserved for those patients who do not tolerate first line therapy. In ad- Follow-Up All patients will be followed at 3-month intervals for evaluation of progression of heart failure, vital status, and quality-of-life. In patients randomized to receive an ICD, follow-up will also include ICD interrogation. Additionally, a 6-minute walk test, a standard 12-lead electrocardiogram, signal-averaged electrocardiogram, and Holter monitoring will be performed annually (Fig. 1). Baseline 1 Vital Status ICD Interrogation Medications Labs* ECG SAECG Holter Walk Test QOL Questionnaires NIPS DFT Adverse Events 3 6 9 12 Post Randomization (Months) 15 18 21 24 27 30 33 36 39 42 V V V V V V V V V V V v V V V V V V ^/ yj V V V ^/ V V ^/ V V V V V* V* V V >/ V * Laboratory testing as clinically indicated only V V V V V V V • DFT testing is optional at 3 & 12 months Figure 1. Follow-up schedule for the DEFINITE study. QOL = quality of life; DFT = defibrillator testing; NIPS = noninvasive programmed stimulation. 340 March 2000 PACE, Vol. 23 DEFINITE The primary endpoint of the study will he total mortality. Any recommendations regarding early terminating of the study hy the data safety and monitoring hoard will he hased on the primary endpoint. Secondary endpoints will include quality-of-life, all-cause specific mortality, and appropriate defihrillator shocks in patients randomized to ICD therapy (Tahle II]. Although inclusion in the study is primarily hased on the presence of LV dysfunction and an arrhythmia marker, the relationship of other variahles, including QT dispersion, arrhythmia density, heart rate variahility, and 6-minute walk test, to patient outcome also will he analyzed in a posthoc secondary analysis. Quality-of-Life This study will include a careful assessment of the effects of ICD implantation and presence on continued quality-of-life, and will he performed using two assessment tools. The SF-12 Quality of Life Questionnaire and the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Quality of life Questionnaire will he completed at each follow-up visit.^^"^^ The mean quality-of-life scores for the ICD and control groups will he compared. In addition, in association with the therapeutic economics calculations, the average quality-of-life and employment and functional status in hoth groups will he examined to estimate these "the quality of life" endpoints in relationship to any determined mortality henefit. Cost Effectiveness Medical care costs for hoth groups will he estimated using a diagnosis-hased methodology. For the initial hospitalization for ICD implant (in patients randomized to ICD) and for any suhsequent hospitalizations or doctor visits the diagnosis, CPT code, and DRC, if appropriate, will he ohtained. For all hospitalizations, length of stay will Table II. Endpoints Primary: Secondary: Total mortality Quality-of-life (QOL) Cost effectiveness Appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator discharges for sustained ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation Cardiac and sudden death mortality Presence, length, and rate of nonsustained ventricuiar tachycardia Appropriate pacemaker backup to severe brachycardia PACE, Vol. 23 he calculated. This will apply to the initial hospitalization and any suhsequent hospitalizations. In addition, all diagnostic tests performed on an outpatient hasis, with the exception of hlood work, will he recorded. Based on these data, a model of estimated medical costs for each suhject in each group will he calculated. The estimated costs will be hased on the standard Medicare reimhursement rate for the individual testing procedure. This will standardize charges across study centers. After an average cost is estimated for the two groups per patient year, it will he divided hy the expected patient year henefit hased on the survival difference hetween the two groups. This will allow a calculation of dollar cost per life saved. The target hypothesis is that the ICD placement in this at risk patient population will result in a cost henefit of < $50,000/year of life saved. ICD Discharges If a significant mortality henefit is demonstrated in the ICD group, an attempt will he made to determine to what degree the mortality henefit is due to the hradycardia hackup support or antitachyarrhythmia conversion ahilities of the ICD. Although ventricular fihrillation (VF) is presumed to he the most common mechanism of sudden cardiac death in this patient population, some studies have suggested that hradycardia may he an important cause of mortality especially in patients with heart failure.^ Each ICD discharge will he classified hy the study site investigator as heing appropriate or inappropriate hased on associated symptoms and standard criteria from intracardiac electrogram analysis. A data report form documenting symptoms associated with an ICD discharged and characteristics of the electrogram will he completed. The analysis of each individual episode will he verified at a core lahoratory. Backup hradycardia pacing will he characterized hased on recall analysis of episodes requiring hradycardia pacing. The numher of subjects in the ICD group who receive appropriate ICD discharges and who use hradycardia hackup will he calculated to provide an estimate of potential causes for the ohserved mortality difference hetween the ICD and control groups. Cause Specific Mortality Determinations of cause specific mortality may he fraught with a numher of errors due to inahility to differentiate hetween death due to pump failure and sudden cardiac death. Therefore, a system of evaluating cause specific mortality recently descrihed hy Epstein et al.^'' will he used in the present study. This scheme examines the prohahle cause of death and the degree of certainty with which the mortality mechanisms can he assigned. March 2000 341 KADISH, ET AL, Statistical Analysis Estimating placebo and treatment event rates in multicenter prospective studies remains a challenge wrhen other changes to standard therapy can substantially effect mortality. An annual placebo total mortality rate of 7.5% was estimated based on available published data at the time of trial deg^gj^ 5,7,8,12,1^.21 -Yhis is lower than the placebo mortality rate in earlier multicenter studies, but was designed to correct for the expected characteristics of this study patient population and for anticipated changes in survival with the use of pblockers. It has been shown that the percentage of patients who experience sudden, as opposed to nonsudden, cardiac death varies depending on the severity of underlying heart failure. Not surprisingly, patients with more severe heart failure are more likely to die of pump failure whereas those with less severe degrees of heart failure are more likely to experience a sudden cardiac arrhythmic death.^ Thus, it was estimated that approximately 55% of the deaths in the current study would be due to sudden tachyarrhythmic or bradyarrhythmic death. Estimating that 90 of these deaths will be prevented by the ICD, a reasonable assumption in patients without severe ischemia, we postulated a 50% total reduction in mortality in the ICD treatment group. A modified two-sided triangular design as described by Whitehead, used in the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Trial (MADIT), was used for statistical calculations^^ and a level of 0.05 was used. Based on these assumptions, it was estimated that 204 subjects would be required in each group. Sample size calculations in the present study are primarily event driven. If the study hypothesis is correct, it will require 66 events to achieve the study endpoint with 85% power. ^""^^ Appendix 1—Centers Christine Albert, M.D., Liz Simpson, B.S., Massachusetts Ceneral, Boston, M/1; James Baker, M.D., Janice Sensing, R.N., The Heart Croup, Nashville, TiV; Anil Bhandari, M.D., Beverly Firth, R.N., M.N., Cood Samaritan Hospital, Los Angeles, CA; Hugh Calkins, M.D,, Karen Braznell, R.N., fohns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD; Sergio Cossu, M.D., Rosanne Dittenber, R.N., Intermedics Health Center, Port Charlotte, EL; James P. Daubert, M.D., Kris Kremer, R,N., University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, ATY; Peter R. Foster, M.D., Tanya Isaacs, R.N., Cardiology Consultants, Indianapolis, IN; Jeffrey Coldberger, M.D., Merribeth Rose, R.N., B.S.N., Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago, IL; Lewis L. Horvitz, M.D., Ceri Schulte, R.N., Cardiovascular Associates Deleware Valley, Cherry Hill, Nf; Robert W. Hull, M.D., Cynthia Chapman, R.N., Ar342 rhythmia Consultants, Creenville, SC; Harry A. Kopelman, M.D., Joni Miller, R.N,, Atlanta Cardiac Croup, Atlanta, CA; Robert Lemery, M.D., Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, RI; Joseph H. Levine, M.D., Molly Nichols, R.N., B.S.N., St. Erancis Hospital, Roslyn, NY; Thomas Mattioni, M.D., Suzanne Welch, R.N., Arizona Heart Institute, Phoeniz, AZ; ]ohn P. McKenzie, M.D., Dodie Wilson, R.N., California Cardiac Institute, Clendale, CA; William Miles, M.D., Diana Marshall, R.N., Southwest Florida Heart Croup, Eort Myers, EL; Andrea Natale, M.D., Laura Martin, R.N., University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY; Behzad B. Pavri, M.D., Linda Coffredo, R.N., M.S.N., University of Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, PA; Paul M. Popper, M.D., Denise Steele, R.N., Cardiology Consultants, Punta Corda, EL; Marc Roeike, M.D., Yolanda Spicer, R.N., Newark Beth Israel Medical Center, Newark, Nf; Mark Rosenthal, M.D., Charlotte Paskman, R.N., Abington Medical, Philadelphia, PA; Stephen Rothbart, M.D., Jackie Matthews, R.N., Newark Beth Israel Medical Center, Newark, Nf; Philip T. Sager, M.D., Rosemary Connelly, R.N., WLA VA Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA; Paul Wang, M.D., Barbara Fitzpatrick, R.N., New England Medical Center, Boston, MA; Raul Weiss, M.D., Doris Cavolich, R.N., Melanie Turkel, R.N., University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA; Stephen L. Winters, M.D., Jennifer Herik, R.N., Kim Wain, R.N., Morristown Memorial Hospital, Morristown, Nf; Joseph Zebede, M.D., Kimberly Vitale, R.N., Mount Sinai Medical Center, Miami Beach, EL. Appendix 2—Committees Steering Committee: Kelley Anderson, M.D., University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA; Mark Estes, M.D., New England Medical Center, Boston, MA; Joseph H. Levine, M.D., St. Erancis Hospital, Roslyn, NY; Alan Kadish, M.D., Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago, IL; Rebecca J. Quigg, M.D., Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago, IL. Data Safety and Monitoring Board: Andrew E. Epstein, M.D., University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL; Kirk Adams, M.D., University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC; Cary Cutter, Ph.D., Center for Research Methodology and Biometrics, Denver, CO; Kenneth Ellenbogen, M.D., Medical College of Virginia, Richmond, VA. Publications Committee: Alan Kadish, M.D., Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago, IL; David Cannom, M.D., Cood Samaritan Hospital, Los Angeles, CA; Joseph H. Levine, M.D., St, Erancis Hospital, March 2000 PACE, Vol, 23 DEFINITE Roslyn, NY; William Miles, M.D., Southwest Florida Heart Group, Fort Myers, FL; Paul Wang, M.D., New England Medical Center, Boston, MA. Events Committee: James P. Daubert, M.D., University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY; Srinivas Murali, M.D., University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA; Behzad B. Pavri, M.D., University of Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadel- phia, PA; Philip T. Sager, M.D., WLA VA Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA; Stephen L. Winters, M.D., Morristown Memorial Hospital, Morristown, NJ. Recruitment Committee: Joseph H. Levine, M.D., St Francis Hospital, Roslyn, NY; Anil Bhandari, M.D., Cood Samaritan Hospital, Los Angeles, CA; Raul Weiss, M.D., University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA. References 1, Luu M, Stevenson W, Stevenson L, Diverse mechanisms of unexpected cardiac arrest in advanced heart failure. Circulation 1989; 80:1675-1680, 2, Moss A, Hall W, Cannon D, Improved survival vi^ith an implanted defibrillator in patients with coronary disease at high risk for ventricular arrhythmia, N Engl J Med 1996; 335:1933-1940, 3, Levine J, Waller T, Hoch D, et al, Implantable cardioverter defibrillator; Use in high asymptomatic individuals. Am Heart J 1996; 131:59-65, 4, Cohn J, Archibald D, Ziesche S, Effect of vasodilator therapy on mortality in chronic congestive heart failure: Results of a Veterans Administration cooperative study, N Engl J Med 1986; 314:1547-1552, 5, Cohn J, Johnson G, Ziesche S, A comparison of enalapril with hydralazine-isosorbide dinitrate in the treatment of chronic heart failure (V-HeFt II—Veterans Health Failure Trial II), N Engl J Med 1991; 325:303-310, 6, Swedherg K, Kjekshus J, Effects of enalapril on niortality in severe congestive heart failure: Results of the Cooperative North Scandanavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS), Am J Cardiol 1988; 62;60A-66A, 7, Fonarow G, Chelimsky-FalUick C, Warner-Stevenson J, Effect of direct vasodilation with hydralizine versus angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition with captopril on mortality in advanced heart failure: The Hy-C Trial, J Am Coll Cardiol 1992; 19;842-850, 8, Pfeffer M, Braunwald E, Moyee L, Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction: Results of the survival and ventricular enlargement trial, N Engl J Med 1992; 327;699-677, 9, Waagstein F, Bristow M, Swedberg K, Beneficial effects of metoprolol in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet 1993; 32:1441-1446, 10, Packer M, Bristow M, Cohn J, The effect of Carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure, N Engl J Med 1996; 334:1349-1397, 11, Heidenreich P, Lee T, Massie B, Effect of beta-blockade on mortality in patients with heart failure: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials, J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 30:27-34, 12, Packer M, Gheorghiade M, Young J, Withdrawal of digoxin from patients with chronic heart failure treated with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhihitors. New Engl) Med 1993; 329:1-7, 13, The Digitalis Investigation Group: The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure, N Engl J Med 1997; 336:525-533, 14, Waldo A, Camm A, DeRuyter H, Effect of d-sotalol on mortality in patients with left ventricular dysfunction and recent and remote myocardial infarction. Lancet 1996; 348:7-12, 15, (CAST) Investigators Preliminary report: Effect of endainide and flecainide on mortality in a randomized trial of arrhythmia sup- PACE, Vol. 23 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, March 2000 pression after myocardial infarction, N Engl J Med 1989; 321:406-410, Singh S, Fletcher R, Fisher S, Amiodarone in patients with congestive heart failure and asymptomatic ventricular arrhythmia, N Engl J Med 1995; 333:77-82, Doval H, Nul D, Grancelli H, Randomized trial of low-dose amiodarone in severe congestive heart failure. Lancet 1994; 1:493—498, Doval H, Nul D, Grancelli H, Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia in severe heart failure. Circulation 1996; 94:3198-3203, Connolly S, Cairns J, Gent M, et al. Effects of prophylactic amiodarone on mortality after acute myocardial infarction and in congestive heart failure: Meta-analysis of individual data from 6,500 patients in randomized trials. Lancet 1997; 350:14,17-1424, Pogwizd S, McKenzie J, Cain M, Mechanisms underlying spontaneous and induced ventricular arrhythmias in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1998; 98:2404-2414, Singh S, Fisher S, Carsion P, et al. Prevalence and significance of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with premature ventricular contractions and heart failure treated with vasodilator therapy, J Am Coll Cardiol 1998; 32:942-947, Grimm W, Hoffmann J, Meni V, et al. Programmed ventricular stimulation for arrhythmia risk prediction in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, J Am Coll Cardiol 1998; 32;739-745, Rector T, Kubo S, Cohn J, Patients self-assessment of their congestive heart failure: Content, reliability and validity of a new measure, the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire, Heart Failure 1987; 3:198-209, Rector T, Cohn J, Assessment of patient outcome with the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire: Reliability and validity during a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of Pimobenden, Am Heart J 1992; 124:1017-1025, Guyatt G, Nogradi S, Halcrow S, et al. Development and testing of a new measure of health status for clinical trials in heart failure, J Gen Intern Med 1989; 4:101-107, Ware J, Sherbourne G, A 12-Item Short-form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity, Med Care 1996; 34:220-233, Epstein A, Carlson M, Fogoros R, et al. Classification of death in antiarrhythmla trials, J Am Coll Cardiol 1996; 26:433^42, Whitehead J, Stratton I, Group sequential trials with triangular continuation regions. Biometrics 1983; 39:227-236, Kim K, DeMets D, Design and analysis of group sequential tests based on the type I error spending function, Biometrika 1987; 74:149-154, Kim K, Tsiatis A, Study duration for clinical trials with survival response and early stopping rule. Biometrics 1990; 46:81-92, Kim K, DeMets D, Sample size determination for group sequential clinical trials with immediate response, Stat Med 1992; 11:1391-1399, 343