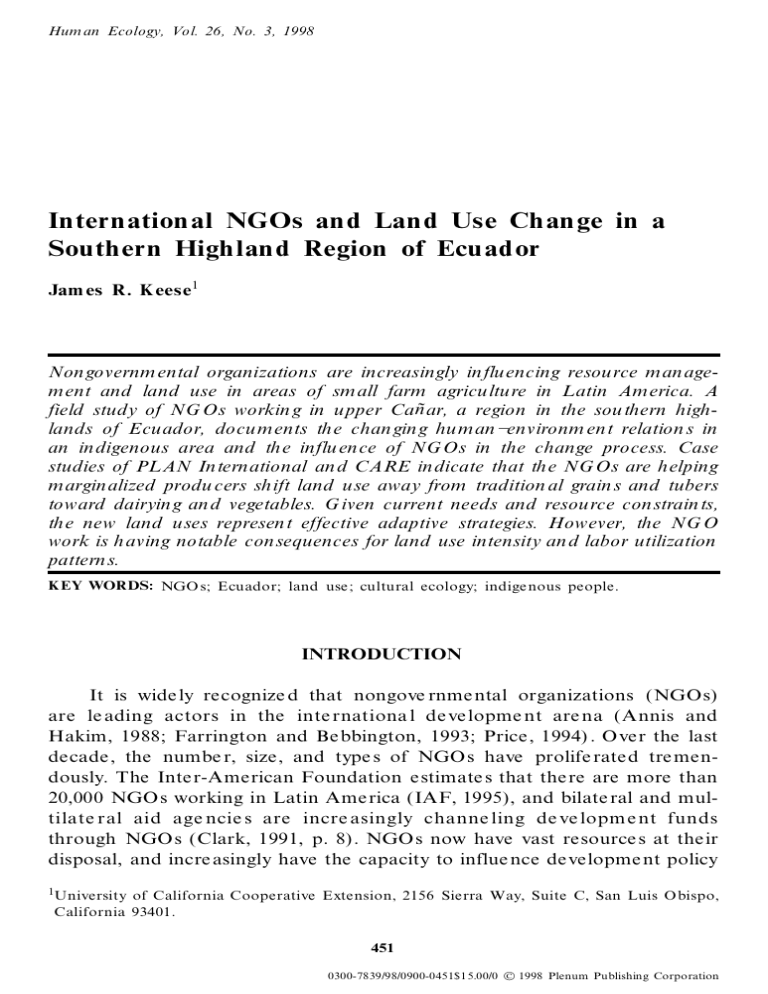

Hum an Ecology, Vol. 26, No. 3, 1998 Internation al NGOs an d Lan d Use Ch an ge in a Southern High lan d Region of Ecu ador Jam es R. K eese1 Non governm ental organizations are increasingly in fluencing resou rce m an agem ent and land use in areas of sm all farm agriculture in Latin Am erica. A field study of NG Os workin g in upper Ca ñ ar, a region in the sou thern highlands of Ecuador, docu m ents the chan gin g hu m an ¯environm ent relation s in an in digenous area and the influ ence of NG Os in the change process. Case studies of PLAN International an d CARE in dicate that the NG Os are helping m argin alized produ cers shift land use away from tradition al grain s and tubers toward dairyin g an d vegetables. G iven current needs and resou rce con strain ts, the new land uses represent effective adaptive strategies. However, the NG O work is h aving notable con sequences for land use intensity an d labor utilization pattern s. KEY WORDS: NGO s; Ecuador; land use ; cultural ecology; indigenous people. INTRODUCTION It is wide ly recognize d that nongove rnme ntal organizations (NGOs) are le ading actors in the inte rnationa l de ve lopme nt are na (Annis and Hakim, 1988; Farrington and Be bbington, 1993; Price, 1994) . O ver the last decade, the numbe r, size, and type s of NGOs have prolife rated tre mendously. The Inter-American Foundation e stimate s that there are more than 20,000 NGOs working in Latin America (IAF, 1995), and bilate ral and multilate ral aid age ncie s are incre asingly channe ling de ve lopm e nt funds through NGOs (Clark, 1991, p. 8). NGOs now have vast resource s at their disposal, and incre asingly have the capacity to influe nce developme nt policy 1 University of California Cooperative Extension, 2156 Sierra Way, Suite C, San Luis Obispo, California 93401. 451 0300-7839/98/0900-0451$15.00/0 Ó 1998 Plenum Publishing Corporation 452 K eese on a global scale and resource utilization at the grassroots. Howe ve r, because of the numbe r, size, and type s of organizations, and because NGOs face a multitude of cultural and environme ntal variable s within rapidly changing local and global conte xts, there continue s to be a nee d for documentation and e valuation of NGO activitie s. Geographe rs who work in cultural e cology have de vote d conside rable re se arch to the nature of tradition al agricultural syste ms in the Third World, and to the impact of outside influe nces and change on resource m a n a ge m e n t a n d la n d u s e ( G r o s s m a n , 1 9 8 1 ; Ma t h e ws o n , 1 9 8 4 ; Nie tschmann, 1973). The re has bee n much discussion about the sustainability of these syste ms, their breakdown as a result of population growth and comme rcialization, and the resulting adaptive strate gie s that are utilize d to maintain the re source base and the social syste m (Be bbington, 1993a; Knapp, 1991; Zimme rer, 1991). O f critical importance to these concerns is the impact of outside de ve lopme nt proje cts on Third World are as where traditional small farm agriculture is pre dominant. Proje cts must consider not only local social and e nvironme ntal conditions and constraints, but also the large r conte xtual factors of a rapidly changing global political economy. Within this conte xt, agricultural e conomists and policymake rs try to ide ntify the conditions unde r which new and more productive methods of production and technical change can be foste red. In this pape r, I de scribe the changing rural conditions face d by smallholde r agriculturalists in highland Ecuador. I then e xamine the NGO impact on land use in uppe r Cañ ar, a re gion large ly inhabite d by indige nous people , and assess the e ffectivene ss of the land use change s as adaptive strate gies to the conte mporary challe nge s faced by smallholde rs of the region. Data gathe re d from the fie ld study of two inte rnational NGOs, CARE and PLAN International, are use d to draw conclusions about the nature of de ve lopme nt by NGOs in the study are a, and the implications for local people and for developme nt policy. This pape r provide s an e mpirical contribution to an unde rstanding of the challe nge s faced by indige nous communitie s in a rapidly changing world, and the role that NGOs play in the modification of the se place s. NGOs, DEVELOPMENT PRIORITIES, AND LATIN AMERICA The term “ NGO ” can be use d to de scribe a varie ty of institutions whose e fforts range from de ve lopme nt work and political lobbying to social and sports clubs (Carroll, 1992, p. xi) . Among the ir many functions, NGOs can de live r re lie f aid, engage in popular organizing, addre ss e nvironme ntal concerns, ope rate de ve lopme nt proje cts, and act as subcontractors or in- NGOs an d Lan d Use 453 te rmediarie s for gove rnments and othe r aid organizations. The origin, nature, and goals of an NGO dramatically affe ct its approach to developme nt, methodology of work, and local impact, as well as its relationship with governments, local communitie s, and othe r NGOs. The focus of this study is on well-funde d, large , international NGOs that e ngage in the de live ry of basic se rvices and provide training and technical assistance in agriculture . The large r concern of this re search is the impact of northe rn-base d de ve lopme nt age ncie s that transfe r re sources and ideas to rural are as in the developing world. The rise in the importance of NGOs in inte rnational de ve lopme nt can be attribute d to many factors. NGOs are ge nerally small-scale , fle xible , lowcost, and task-orie nte d. In ge ne ral, they are le ss bure aucratic than gove rnme nts, have shorte r line s of communication, and stre ss participatory methods of ope ration that include local pe ople in proje ct planning, imple mentation, and assessment (Clark, 1991; Farrington and Be bbington, 1993) . NGOs have prove n to be good at finding innovative and appropriate solutions to proble ms, de live ring important basic se rvices, disseminating ne w ideas, and maximizing the use of local resource s. So-calle d third-ge ne ration NGOs in Latin America have sought a pragmatic developme nt approach that links e cological and e conomic concerns through a strate gy of sustainable de ve lopme nt and rational land use (Price, 1994). 2 In addition, participatory grassroots de ve lopme nt e fforts carried out by NGOs are conside red by many to be the most e ffective way to bridge the gap betwee n poor communitie s, large aid organizations , and gove rnme nt age ncie s (Annis and Hakim, 1988, p. 1; Bunch, 1982, p. v). During a time whe n gove rnme nt programs are ofte n pe rceive d as large , inefficie nt, and corrupt, the NGO se ctor has bee n laude d for being private , small-scale , and decentralize d. NGOs are playing a significant role in mediating the impact of the neolibe ral policie s of structural adjustme nt at the grassroots le ve l (Carroll, 1992; Clark, 1991; Fishe r, 1993) . The imposition of auste rity measure s has re sulted in a dramatic decrease in the size of gove rnme nts in Latin Ame rica, includin g E cuador (Me ye r, 1993) . Resource -poor and ge ographical ly isolate d are as, and poor and politically weak social groups, are especially affe cted by the re duction of gove rnme nt service s and de ve lopme nt assistance . This has create d an institutional void. Foreign finance d NGOs ofte n fill the gaps in gove rnmental programs resulting from auste rity measure s, structural adjustme nt programs, and the failure of public institut ions ( Farringto n and Be bbington, 1993) . Price (1994, p. 46) states that “ the international community incre asingly views 2 NGO s formed in the 1940s and 1950s focused on direct relie f aid. The focus of many NGO s in the 1960s and 1970s was on popular organizing and grassroots democracy. 454 K eese third-ge ne ration NGOs as the most effe ctive and e fficie nt means to support change .” Be bbington (1993b) and Clark (1991) warn, howe ve r, that the effe ctive ness of NGO actions should not be assume d. NGO interests can vary greatly, often putting them in conflict with each othe r or with gove rnme nts, and the lack of coordination within the NGO sector ofte n results in the duplication of se rvices and a waste of re sources. In addition, NGO proje ct methodologie s use d in the fie ld can cause division and conflict within project communitie s. Pate rnalism and the ove r-re liance on give -aways are espe cially proble matic. Fore ign gove rnme nts and inte rnational donors too ofte n be lie ve that if the funds ge t to the grassroots, they do the right thing. Issues of accountability, assessment, and impact are of critical importance to the study of NGO proje ct activitie s. Rese arch in cultural and political ecology provide s a framework for analyzing and unde rstanding the impact of NGOs on local resource manage ment practice s in the Third World. Cultural e cology defines the local ethno-scie ntific knowle dge and relations betwee n cultural practice s and resource manage ment. Political ecology inte grate s land-use practice s with the local ¯global political e conomy (Pe e t and Watts, 1993) . It addre sse s the nee d to link traditional resource manage ment and environme ntal regulation strate gies of peasant communitie s and organizations into the large r context of ope n and changing political economie s (Zimme rer, 1991) . Much work in cultural e cology has focused on traditional agricultural systems and the inve stigation of adaptive strate gie s used by local people s in re sponse to change (i.e., Knapp, 1991; Mathe wson, 1984; Nietchsmann, 1973; Turne r 1989) . Recent work in political e cology has emphasize d the ne ed to consider current influe nce s and constraints and the large r conte xt in which traditional syste ms ope rate (i.e., Bassett, 1988; Bebbington, 1993b; Z immere r, 1993) . This pape r examine s changing rural conditions in highland Ecuador, the conse que nce s of NGO activitie s on crop choice within an area of traditional Ande an highland agriculture , and the e ffectivene ss of the NGO-induce d land-use change s as adaptive strate gie s to current resource and contextual constraints. THE CHANGING RURAL CONTEXT IN HIGHLAND ECUADOR Ecuador is commonly divide d into thre e ge ographic regions The coastal lowlands, or Costa, make up the coastal plain and are a betwee n the Andes Mountains and the Pacific O cean. The highland re gion, known as the Sierra, runs down the middle of the The lowlands in the Amazon basin to the east of the highlands are (Fig. 1). foothills Ande an country. referred NGOs an d Lan d Use 455 Fig. 1. Ecuador and re gions. to as the Oriente. The topography and e cological conditions of the country are e xtre mely varie d, ranging from dese rt to tropical rain forest to highland 456 K eese tundra, or p áram o (Southgate , 1990, p. 74) . Approximate ly half of Ecuador ’s 11.5 million pe ople live in the Costa region, 46% in the Sierra, and only 4% in the Oriente. O ver the last 40 years, Ecuador ’s population has triple d (Tello-E spinosa, 1994) resulting in inte nse land pressure . Agricultural mode rnization, influe nced both by the Ecuadorian gove rnme nt and demand from foreign markets, has contribute d to dramatic social and environme ntal change within Ecuador. Ecuador ’s rural are as exhibit patte rns of une ven developme nt which are characte rize d by notice able historic, e conomic, and social difference s. The Sierra is a re gion of e xte nsive e state s (hacien das) and subsiste nce agriculturalists, whe re landlords historically have exhibite d high le vels of social and political control. In contrast, the Costa is dominate d by commercial banana, rice, sugar cane , and shrimp farms using modern capitalist production technique s and e mploying wage labor. Within this structure are thousands of small, marginalize d, highly fragm e nte d holdings, or m inifundios (Brown et al., 1988; Lawson, 1988; Redclift and Preston, 1980). The m inifun dios are holdings of less than 10 ha and are worke d by poor pe asant farmers who e ke out a living by cultivating traditional crops and obtaining te mporary off-farm work. Most of the approximate ly 1.5 million indige nous Q uichua speake rs in Ecuador live in the Sierra. The traditional economy of the Ecuadorian highlands involve s farming of potatoe s, corn, be ans, barle y, and whe at in the basins; and the grazing of cattle , she ep, and camelids in the basins and on the high plate aus or p áram o ( 3200 ¯3500 m) (Stewart et al., 1976) . Smallholde r production in the Sierra is mostly for subsiste nce or the dome stic market, but is hinde re d by re source constraints and has suffe red from stagnation. O ver the last four decades or so, Ecuador ’s rural are as have be en dramatically transforme d. During the 1960s and 1970s, land re form was carried out in order to fre e up de pende nt hacie nda labor and to modernize production, primarily for the purpose of mee ting growing de mands for food in the citie s and the de mands of fore ign marke ts and produce rs. Agriculture on all farm size s has become more commercialize d (Commande r and Pe ek, 1986) . Howe ve r, gove rnme nt agricultural policie s have had une ven spatial and sectoral impacts (Lawson, 1988) . Large produce rs, the e xport se ctor on the coast, and urban consume rs have be en the primary be ne ficiarie s of import substitution industrialization policie s and agricultural subsidie s that e mphasize comme rcialization of production. Me anwhile , the small farm sector and indige nous highland communitie s have ge ne rally be e n ne glected, resulting in marginalization and outmigration. Urbanization and agricultural mode rnization have also contribute d to a transformation of labor utilization patte rns in Ecuador, re sulting in high rates of temporary labor circulation and permane nt outmigration. In 1950, NGOs an d Lan d Use 457 72% of the pe ople live d in rural are as. By 1990, the proportion had droppe d to 45% . Tello-E spinosa (1994) predicts that by the year 2000 only 20% of the population will be living in rural are as. Before 1962, Ministry of Agriculture (MAG) data indicate that 20% of the total income that small farmers e arne d was from wage s; by 1974, that numbe r had increase d to 62% (se e Pee k, 1980) . Today, se asonal migration, primarily to urban are as and the comme rcial farms in the Costa and temporary off-farm labor have become the norm. Z imme re r’s (1991, 1993) work in Pe ru and Bolivia reveals similar tre nds, indicating that increase d depende nce on off-farm labor by the traditional sector is not an isolate d phe nomenon. Since the 1970s, agricultural production in highland Ecuador has not only be came more market oriente d, but crop choice has shifte d as well. The most significant change has be en the expansion of dairy farming, resulting in a substantial incre ase in the area unde r pasture (Commande r and Pee k, 1986) . There are a numbe r of re asons for this change . The growing process of urbanization and bette r transportation links be tween the rur al Sierra and urban are as fue le d de mand. Rapid incre ase s in urban income s and changing national pre fe re nce s shifte d demand toward products with highe r income elasticitie s like animal prote ins, fruits, vegetable s, and se afood, and away from traditional cere als and tube rs (Whitake r and Colye r, 1990, p. 27) . Also, gove rnme nt subsidie s and pricing policie s foste red more capital-inte nsive farming and dairying. Incre ased dairying has occurre d across all farms size s, but especially on medium and large farms (Commande r and Pee k, 1986) . Minifu ndio production has also moved toward a more dive rsified and market-orie nted crop mix (Commande r and Pee k, 1986) . Howe ver, despite relative price differe ntials favoring dairy products and vege table s and discouraging the production of traditional staple s, a whole sale shift toward the se products has not be e n witne sse d among indige nous smallholde r agriculturalists in many parts of the Sierra (including Cañ ar). The low response within the traditional sector to the large r proce ss of technical change in agriculture can be attribute d to several factors (Ellis, 1988; Stevens and Jabara, 1988) . First, culture plays a role in the choice to grow traditional grains and tubers. Second, agricultural innovation and conve rsion e ntails a certain level of risk. Indige nous agriculturalists are generally ave rse to risk taking because they ofte n live at or ne ar subsiste nce level. Howe ver, the third and most important re ason why many indige nous farme rs are not shifting on a large r scale toward dairying and vege table s is be cause of limited acce ss to re sources, notably capital, purchase d inputs, and te chnical information. NGOs in Ecuador regularly work with farme rs who must deal with the se proble ms. 458 K eese Substantial and sustaine d oil reve nue s obtaine d from production in the Oriente has facilitate d the rural transformation process in Ecuador. In general, the Ecuadorian gove rnme nt has carried out developme nt policie s in a highly centralize d and top-down manne r (Lowde r, 1991) . Howe ve r, a drop in oil price s during the 1980s led to a pe riod of structural adjustme nt and auste rity that continue s to the present. During this period, the state prove d to be incapable of addre ssing (or unwilling to addre ss) the ne eds of all of Ecuador ’s citizens (Alternativa and PNUD, 1992). NGOs have emerged to fill the institutional void left by reduced gove rnme nt budge ts and lack of atte ntion to small farmers in the highlands. Unde rfunde d Ecuadorian gove rnme nt age ncie s openly e ncourage inte rnational NGOs to enter impove rishe d are as and provide de ve lopm e nt se rvice s ( Torre s, 1994) . NGOs have become important actors working in marginalize d rural communitie s, he lping the m to maintain themselve s and adapt to the challe nge s pre se nte d in a rapidly changing national and international context. NGOs AND LAND USE CHANGE IN UPPER CAÑAR The study area for this research is the uppe r drainage are a of the Ca ñ ar Rive r, commonly known as uppe r Ca ñ ar (Fig. 2). Upper Ca ñ ar is a topographically and agroe cologically dive rse re gion ranging from 800 to 4500 m above se a leve l. The population of the region is approximate ly 65,000, half of which are indige nous people who constitute a majority in the rural areas. The change s outline d above affecting the Ecuadorian Sierra are ge nerally affe cting uppe r Cañ ar in similar ways. The traditional e conomy of the re gion is becoming more commercialize d, with approximate ly 50% of traditional staple crops now being sold in local marke ts. For most familie s, the available land is not sufficie nt to utilize all of the available labor or to generate the cash income ne ede d to meet house hold ne eds. Data from the fie ld show pe r capita income from on-farm production to be $96 pe r hectare of land owned. Current pre ssure on the land in the more densely populate d zones has create d a situation where cam pesinos are looking to the less populate d but more fragile zone s as a means of gaining access to more land and resource s. Meanwhile , the Ecuadorian gove rnment has done little to limit de structive land use practice s. It is commonly stated by local farmers and NGO worke rs that through repeate d cultivation and the elimination of fallowing, soil fertility has decline d. Ste ep slope s are commonly deforested, plowe d, and cultivate d, e xposing the m to erosion. The de te rioration of production in uppe r Ca ñ ar, le ading to lower yie lds and income s, along with increased availability of off-farm work, has stimulate d seasonal migration. Income from migration NGOs an d Lan d Use 459 Fig. 2. Uppe r Cañ ar. and othe r off-farm labor large ly sustains a community economically and serves to dive rsify the income base . Four international NGOs have worke d in uppe r Cañ ar promoting land use change s. The focus of this pape r is on the actions of PLAN International and CARE-PRO MUSTA. 3 These two NGOs were chosen because the y have the large st budge ts, work in the most communitie s in the re gion, and have the most compre hensive programs. They are typical of the wellfunde d international NGOs that engage in inte grate d community de ve lopment. In ge ne ral, the NGOs work with the poore st people in the poore st communitie s (familie s owning 5 ha or more of land usually do not ne ed or want NGO assistance ). Fieldwork was conducte d ove r a 9-month pe riod during 1994 and 1995, with follow-up communication in 1996. I colle cted data using a combination of participant obse rvation and semistructure d, unstructure d, and inform al inte rvie ws with community me mbe rs, NGO workers, gove rnment officials, and othe r affected inte re sts. I gathe re d data from nine communitie s, but I spent more time in the two communitie s describe d in the following case studie s. 3 The other international NGO s that have worked with agriculture in the re gion are the Lutheran Mission (Norway) and World V ision (U.S.). 460 K eese PLAN is an inte rnational humanitarian, child-sponso rship deve lopment organization without religious, political, or gove rnme ntal affiliation (PLAN, 1994b). PLAN ope rate s in 33 countrie s in the world, with an annual budge t (1994) of over $206 million, and has operate d since 1982 in the rural are as of Ca ñ ar Province . PLAN is the large st NGO working in the province , both in numbe r of proje cts and budge t: currently it has proje cts in 45 com munit ie s in up pe r Ca ñ ar, with an an nu al budge t of $1,404,755 (PLAN, 1994a) ,4 making its impact in the uppe r Ca ñ ar the most important of all organizations (state or nongove rnmental) working in the region. PLAN enrolls childre n and then provide s proje ct assistance to familie s and communitie s in the areas of infrastructure , agriculture , education, sanitation, he alth, fore stry, small busine ss and income ge ne ration, and community organization. A de taile d study of a PLAN proje ct in the indige nous community of Sunicorral San Juan provide s a clear indication of PLAN’s impact on land use change in uppe r Cañ ar. PLAN began work in the community in 1986 and finance d proje ct activitie s through fiscal ye ar 1996 (ending in June of 1997) . PLAN worked with a group of 23 agriculturalist familie s (in a community of 75 familie s). The se we re the familie s most affe cted by the barrie rs to developme nt that I describe d above . PLAN foste rs the conve rsion of land away from the cultivation of traditional grains and tube rs, in favor of the planting of pasture for dairying, and the cultivation of vege table s for subsiste nce and sale . In 1993, PLAN helpe d the proje ct familie s buy a 1.5 ha plot within the community to serve as an irrigate d pasture . The cost of the land was $1365, of which PLAN paid 80% and the familie s paid 20% . In 1994, PLAN built a modern irrigation syste m utilizing a gravity flow system (with cement holding tank) and rain-bird style sprinkle rs. The total cost of the irrigation syste m was $6820. The plot supports approximate ly se ve n additional cows. PLAN has also provide d support for veterinary assistance , bree d improve ment, and pasture improve ment. Milk is sold at a colle ction point in El Tambo and ge nerates an ave rage annual income (afte r e xpe nses) pe r cow of $187. In 1993, PLAN began providing assistance for inte grate d family gardens. An integrate d family garde n include s a 10 ´ 10-m space for vegetable production, e arthworm raising for humus, small animals (i.e ., pigs, shee p, guine a pigs, and chicke ns), and a .25 ¯.5-ha plot of pasture . PLAN provide d fe ncing mate rial, see ds, earthworms, and training for the layout and implementation of the garde n proje cts. V ege table s (not part of the traditional 4 PLAN Cañ ar’s budget finances approximately 150 projects in the province s of Ca ñ ar and Azuay. NGOs an d Lan d Use 461 diet) add to family nutrition, and any surplus is sold in the El Tambo marke t. V ege table s are bought and trucked to nearby citie s and to the Costa, and the y are some time s exporte d (by intermediarie s) to northe rn Pe ru. Average annual income from vege table s (afte r expe nse s) is $78 pe r family. PLAN adde d pigpe ns (chan cheras) to the inte grate d garde n proje cts in 1994 to he lp promote the raising of pigs. Pigs, which are part of the traditional system, provide a valuable source of income (sold in the Ca ñ ar live stock market), meat, and manure . PLAN proje ct assistance has adde d anothe r $45 of income pe r PLAN family as a re sult of sales of pigs and cattle. In 1986, virtually all of the land in the community was used for fie ld crops. In 1995, approximate ly 27% of the land in Sunicorral was de vote d to cultivate d pasture , with small but significant pieces of land de vote d to vege table production. A fundame ntal land use conve rsion is occurring in Sunicorral with PLAN’s assistance . The agricultural activitie s of the PLAN proje ct with 23 familie s in Sunicorral are summarize d in Table I. The high up-front cost of the pasture proje ct subsidize s production change s but allows participating familie s to realize immediate income bene fits. The use of e xpe nsive inputs and modern technology (rain-bird sprinkle rs) may not be justifie d economically, and raise s the proble m of pate rnalism and depende nce . PLAN pe rsonne l justify the costs and methods be cause the y hope that the proje ct activitie s will be copie d by nonproje ct familie s. In this way, new innovations initiate d by PLAN will diffuse to othe r communitie s resulting in a significant multiplie r bene fit to the region. Be side the obvious income -ge nerating e ffects of the PLAN proje ct, increasing land are a unde r pasture has the be ne fit of reducing the risk of erosion (assuming overgrazing doe s not occur). Pasture land is less susceptible to the effe cts of water- and wind-induce d e rosion than is land that is Table I. Cost Breakdown for Plan Project Activities in Sunicorral Data 1993 1993 - 96 1994 - 95 1994 - 96 Activity 1 ha community pasture household gardens irrigation syste m pig raising/pens Total Net bene fit: $43/capita/ye ar or 50% increase a Project cost Annual income $1365 250 a $6820 960 — $78/family $55/family b $45/family $9,395 c $178/family Estimate base d on $10/family for materials. Pasture and irrigation project income are combined. c Cost for land and materials only; local costs for pe rsonne l, office, and transport are not available. b 462 K eese regularly plowe d or “ broke n ” for crop cultivation. In addition, improve ments in soil fertility can be expe cted as a result of the land use change s influe nced by PLAN. The rotation of cultivate d pasture with fie ld crops allows for a fallowing effe ct, and the increase in live stock raising of all type s within the house hold production syste m increases manure availability; the by-product of both activitie s being the reduction in ne ed for purchase d chemical fertilize r. PLAN’s proje ct is having diffe ring effe cts on labor utilization. The promotion of cattle raising re sults in a reduction of labor demand for some plots, because raising cattle require s less labor than crop cultivation. Given the importance of off-farm work, promoting live stock thus incre ase s agricultural income while de creasing on-farm labor re quire ments. This action is part of the large r trend in the dive rsification of the highland economy. It is an effe ctive strate gy to cope with the de mands of the contemporary conte xt. In contrast, the introduction of community garde ns is a means of inte nsifying the use of small plots in the imme diate vicinity of a house . Many house holds own less than 1 ha, so maximizing the use of all available land is critical. By de sign, wome n are ge ne rally re sponsible for the garde n proje ct activitie s. PLAN doe s this as a means of e mpowe ring wome n, which it fe els is linke d to child welfare. Se veral familie s in Sunicorral have begun to e xpe riment with large r plots, usually .25 ha in size , of monocroppe d vege table s; cabbage , carrots, and onions are most commonly grown. If vegetable production continue s to move out of the garde ns and into the fie lds, the n the labor save d with the introduction of cattle will be shifte d toward the highe r-value ve getable crops. The second organization unde r revie w is CARE Inte rnational. CARE is an international NGO that finance s and administe rs developme nt programs in 60 le ss-de ve lope d countrie s. E ve ry ye ar, CARE Inte rnational spe nds more than $600 million in e merge ncy and sustainable de ve lopme nt funds that benefit more than 30 million people (CARE, 1994) . CARE ’s Proye cto Mane jo de l Uso Soste nible de las Tie rras Andinas de l Ecuador, or Sustainable Ande an Land Use Manage ment Proje ct (PRO MUSTA) is focused on the area of agricultural and natural re sources. PRO MUSTA was founde d in 1988 through the consolidation of CARE ’s Communal Forestry Proje ct with the efforts of the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock’s soils division. 5 PROMUSTA ’s national budge t for the funding pe riod 1988 ¯ 1996 was $5 million (CARE, 1995). 6 PRO MUSTA Ca ñ ar worked in 22 5 6 PRO MUSTA is administratively conside re d an Ecuadorian national NGO , even though the national administration and project methodology come from CARE. The CARE-PRO MUSTA budget re ceive s $3,000,000 from CARE, $1,340,000 from MAG, and the re st from international donors and from provincial and municipal gove rnments within Ecuador. NGOs an d Lan d Use 463 communitie s in uppe r Ca ñ ar with an annual budge t of approxim ate ly $75,000. Sustainable land use and production manage ment are promote d by using demonstration plots, pasture improve ment, live stock raising, conservation agriculture , agrofore stry, and forest manage ment and prote ction. A de taile d study of a PRO MUSTA proje ct in the indige nous community of Ramos Huray illustrate s the NGO impact on land use change in uppe r Ca ñ ar. PRO MUSTA e nte re d Ramos Huray in 1992, and at the time the fie ldwork for this pape r was conducte d had worked in the community for 3.5 years. The numbe r of participating familie s in the proje ct varie d from 14 to 23 (in a community of 27 familie s). The PRO MUSTA proje ct in Ramos Huray was most active in the are as of forestry and agrofore stry, conse rvation agriculture , live stock improve ment, and vegetable production. The proje ct work with live stock and ve getable s is consiste nt with the land use influe nce s of PLAN and the othe r organizations working in uppe r Ca ñ ar. Howe ve r, PRO MUSTA place d gre ater emphasis than othe r organizations on soil and conse rvation e fforts. PRO MUSTA, like PLAN, promote d dairying and vegetable production. A veterinary health course emphasizing dairying was give n in cooperation with the gove rnme ntal rural de ve lopme nt age ncy. The obje ctive of the course was to show community members how to treat common cattle disease s and infections, using local re medie s when possible , and be tter animal care. Along with animal health, PRO MUSTA helpe d to improve 5 ha of pasture (de monstration plots) by planting rye grass, blue grass, and clover as cultivate d pasture . The results of improve d animal health and pasture s, although undocume nte d, might re asonably ge ne rate $62.40 from increased milk production (1 liter per day incre ase ove r 8 months) and $87.00 from cow sales (one additional calf e ve ry 3 ye ars). Howe ve r, the lack of ve rifiable data on these numbe rs makes any conclusions tenuous. The scarcity of data is a proble m that plague s atte mpts to assess the impact of NGOs in gene ral. PRO MUSTA introduce d ve ge table garde ning as part of the recent emphasis on income -producing proje cts, giving training and see ds to get the garde ns started. Earthworms are raise d along with the garde ns as a means of producing organic fertilize r. Unlike PLAN, PRO MUSTA he lps with community garde ns, rathe r than individual house hold garde ns. The garde ns are usually worke d by groups of wome n and childre n. It is unce rtain how much income from ve ge table production will be generate d because Ramos Huray is locate d approximate ly 10 mile s from the ne arest marke t center (Suscal) , and with inte rmittent acce ss to irrigation water and se asonal torrential rains, vegetable production may not le ad to a surplus of ve getable s for sale . Neve rthele ss, land in Ramos Huray is be ing use d to produce vege- 464 K eese table s, and PRO MUSTA promote s vegetable production in othe r agroe cological zones within uppe r Cañ ar. A total of 2500 tree s (a varie ty of Ande an alde r, pine s, cypre ss, and eucalyptus) have be en sold to community membe rs since 1992. These tre es were use d for reforestation of stee p slope s, stre am-bank stabilization, and for silvo-pastoral proje cts that line fie lds and pasture s. Tre e planting stabilize s soil, he lps retain soil moisture , can contribute organic mate rial to the soil, and provide s a future source of wood. Proje ct activitie s in conservation agriculture have promote d physical barrie rs to e rosion (te rraces and de viation tre nche s), contour plowing, crop rotation, composting, natural pest control, improve d see d sele ction, and demonstration plots. The goals of the proje ct activitie s in conservation agriculture are to improve the productivity and sustainability of traditional agriculture . The y have not resulted in fundame ntal change s in land use . Howe ve r, the pre se nce of activitie s such as tre e planting, contour plowing, and barrie rs to e rosion have noticeably alte red the look of the indige nous landscape . PRO MUSTA ’s e fforts provide clear example s of what Knapp ( 1994) and Sundbe rg ( 1994) have describe d as the NGO landscape , meaning visible feature s on the land showing the effe cts of NGO work. PRO MUSTA ’s influe nce s on land use and labor utilization are less dramatic than PLAN’s. Erosion control and soil fe rtility enhancing measure s re quire increase s in labor input, but result in highe r le ve ls of production, the refore re pre se nting an intensification of agriculture . Howe ve r, as pre viously state d, this action is inte nde d for the mainte nance of traditional agriculture , and the community has bee n able to mobilize the ne cessary labor during slack pe riods in the migratory and agricultural cycle s. In Ramos Huray, which is locate d in a lowe r agroe cological zone than Sunicorral, cattle alre ady playe d a central role in the local economy. PRO MUSTA is helping to make cattle raising more e fficie nt and compe titive , rathe r than promoting its increase d use, resulting in a minimal impact on labor or land use inte nsity. Garden plots are a more recent introduction to Ramos Huray and the surrounding communitie s, and the expe cted shifts in land use inte nsity and labor utilization have yet to be observed. CONCLUSIONS Traditional human ¯environme nt relationships in indige nous are as in developing countrie s have unde rgone dramatic change s over the last fe w decades. The case of highland Ecuador indicate s that e conomic transformation, a changing policy e nvironme nt, and population growth have contribute d to urbanization, migration, land pre ssures, and land degradation. NGOs an d Lan d Use 465 Commercialization of the traditional e conomy, market inte gration, the ne ed and de sire for cash income s, and labor circulation prese nt new challe nge s to the indige nous farme rs in uppe r Cañ ar. The conditions of a conte mporary context have demande d that new adaptive strate gie s be imple mented if the se communitie s are going to successfully maintain the mselves. Political ecologists are concerned with the outcom es of the se change s, and NGOs are among the principal developme nt age nts affe cting the way re sources are manage d and allocate d. In highland Ecuador, a structural shift away from traditional grains and tube rs toward dairying and ve getable production for market is be ing obse rve d, e spe cially on holdings large r than 10 ha. Howe ver, indige nous smallholde rs ofte n lack the re sources ne ede d to succe ssfully make the transition in land use in order to take advantage of curre nt marke t opportunitie s. The Ecuadorian gove rnme nt’s agricultural de ve lopme nt policie s have consiste ntly be en biase d toward large r produce rs, the export se ctor, and urban areas. NGOs have steppe d in to fill the gap. The case studie s of PLAN International and CARE proje cts in uppe r Cañ ar indicate that NGO assistance serves to buffe r risk and provide the capital and te chnical information ne cessary for succe ssful land use conve rsion among indige nous smallholde rs. The se NGOs, and othe rs, are using similar de ve lopme nt strate gies outside of Ecuador and Latin America, thus indicating a wider patte rn of NGO promotion of dairying and vegetable s. This pape r has provide d an e mpirically-base d community-le ve l analysis of a topic that is not well-de velope d in the lite rature on NGOs. O ne of the principal goals of NGO work is to jump-start a de ve lopment proce ss that be comes se lf-ge nerating and diffuse s to nonparticipating community members, and ultimate ly to neighboring nonproje ct communities and regions. In the case of uppe r Cañ ar, this diffusion process was not obse rve d. The NGOs themselve s are the age nts of diffusion that bring dairying and ve ge table s to margina lize d produc e rs and communitie s. Rather than fostering a bottom-up process from the grassroots, the NGOs are facilitating and accele rating adaptive strate gies among smallholde rs and indige nous people that are gene rally drive n by large r marke t and policy proce sse s. The NGO role is one of he lping a certain group ove rcome the barrie rs to technical change , thus fulfilling a ne ed that is not met by either public policy or marke ts. In addition to the land use change s be ing promote d by NGOs, their work is also having notable impacts on land use inte nsity and labor utilization. All of the ne w land uses promote d by NGOs result in an increase in either production and/or income pe r unit are a. Howe ve r, the NGO work is having differing impacts on labor utilization practice s. Land plante d in pasture for live stock (inste ad of field crops) require s le ss labor input per 466 K eese unit are a than land cultivate d in traditional fie ld crops. This action fre es up male labor for off-farm cash-e arning activitie s. In contrast, vegetable production re pre se nts an inte nsification of the land imme diate ly around a house . Both activitie s are increasing labor require ments of wome n. Women ge ne rally are re sponsible for the vegetable garde ns, for milking the cows, and for the sale of any surplus produce or milk. With production shifts toward dairying and vegetable s, wome n are gaining more control ove r the food supply and family income , which despite heavy work de mands most wome n already face , could be interpre te d as empowering for wome n. The NGOs do this by de sign. As a whole , the NGO work in uppe r Cañ ar give s wome n more control ove r agriculture , while it has the uninte nde d consequence of making it e asie r for the men to migrate and work off the farm. When viewed within a large r e conomic context, this re allocation of labor is e conomically rational in that it aids indige nous smallholde rs to maximize house hold income . Furthe r study on the NGO impact on labor utilization patte rns would undoubte dly yie ld much information about changing ge nde r relationships within the indige nous house hold and community. In addition, the land use change s discusse d in this pape r re pre se nt a departure from traditional production patte rns, which will certainly have implications for community organization and traditional culture . In conclusion, I sugge st that the NGO-induce d change s do represe nt effe ctive adaptive strate gies for traditional agriculturalists in highland Ecuador, give n the myriad of change s that are occurring both locally and nationally. NGO work generally has the effe ct of he lping indige nous pe ople ove rcome the barrie rs to land use conve rsion within the context of curre nt re source constraints, marke t opportunitie s, and gove rnme nt inatte ntion. Per capita income increases of up to 50% were docume nte d in the PLAN International study community. The de mand for dairy products and vegetable s in the urban are as continue s to grow along with urbanization, indicating a conditio n of e conom ic sustainability for the ne w land use s. Howe ver, the NGOs are in effe ct subsidizing the land use change s. It is uncertain what will happe n whe n the NGOs withdraw their support. CARE recently initiate d a follow-up study in Ecuador to try to answe r this question. In addition, despite the docume nte d e conomic and e cological improve ments among proje ct participants, each NGO only works with a small numbe r of familie s in re lative ly fe w communitie s, thus raising questions about the wide r impact of the NGO work and its cost effe ctive ness. This doe s not mean that NGOs are ineffe ctive as age nts of de ve lopme nt. The rise of the NGO se ctor is still re lative ly ne w, and more research into the impacts of the ir e fforts continue s to be ne cessary. NGOs an d Lan d Use 467 REFERENCES ALTERNATIV A (Fundaci ó n Alternativas para e l Desarrolo) , and PNUD (Programas Nacione s Unidas para el Desarrollo) 1992. Directorio de Organ izaciones no G ubernam entales Dedicadas al Desarollo en El Ecuador. Quito. Annis, S., and Hakim, P. (eds.) (1988) . Direct to the Poor: G rassroots Developm ent in Latin America. Lynne Rie nner Publishers, Boulder. Bassett, T. J. (1988) . The political ecology of peasant-herder conflicts in the northern Ivory Coast. Annals of the Association of Am erican G eographers 78: 453-472. Bebbington, A. J. (1993a) . Fragile lands, fragile organizations: Indian organizations and the politics of sustainability in Ecuador. Transactions of the Institute of British G eographers 18: 170-196. Bebbington, A. J. (1993b) . Modernization from below: an alternative indigenous developme nt? Econom ic G eography 69: 274-292. Brown, L. A., Bre a, J. A., and Goetz, A. R. (1988) . Policy aspe cts of developme nt and individual mobility: Migration and circulation from Ecuador ’s rural Sierra. Econom ic G eography 64: 147-170. Brown, L. A., Sierra, R., Southgate, D., and Labao, D. ( 1992) . Complementary perspective s as a me ans of understanding regional change: Frontier settlement in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Environm ent and Planning A 24: 939-961. Bunch, R. (1982). Two Ears of Corn: A G uide to People-Centered Agricultural Im provem ent. World Neighbors, Oklahoma City. CARE (1994) . CARE Annual Report. CARE International, Atlanta. CARE (Ecuador) (1995) . Proyectos en ejecuci ó n. CARE Ecuador, Quito. Carroll, T. F. (1992). Interm ediary NG Os: The supporting link in grassroots developm ent. Kumarian Pre ss, West Hartford, CT. Clark, J. (1991) . Dem ocratizing Developm ent. Earthscan Publications Ltd., London. Commande r, S., and Peek, P. (1986) . Oil exports, agrarian change and the rural labor process: The Ecuadorian Sierra in the 1970s. World Developm ent 14: 79-96. Ellis, F. ( 1988) . Peasant Econom ics: Farm Households and Agrarian Developm ent. Cambridge University Press, Ne w York. Farrington, J., and Bebbington, A. ( 1993) . Reluctant Partners? Non-G overnm ental Organ izations, the State and Sustainable Developm ent. Routledge, London. Fisher, J. (1993) . The Road from Rio: Sustainable Developm ent and the Nongovernm ental Movement in the Third World. Praeger, London. Grossman, L. (1981) . The cultural ecology of economic deve lopment. Annals of the Association of American G eographers 71: 220-236. IAF (Inter-Ame rican Foundation) ( 1995) . A G uide to NG O Directories: How to Find Over 20,000 Nongovern mental Organization s in Latin Am erica and the Caribbean. IAF, Arlington, VA. INEC (Instituto Nacional de Estad ística y Censos) (1987). Mapa de Supervisi ó n Censal de la Provincia Ca ñ ar. INEC, Quito. Knapp, G. (1991) . Andean Ecology: Adaptive Dynam ics in Ecuador. Dellplain Latin American Studies, No. 27, Westview Pre ss, Boulder. Knapp, G. ( 1994) . Endangered Cultural Landscapes of the Equatorial Andes. Paper prese nted at the 1994 Annual Meeting of the Association of American Geographer s. San Francisco, March 31. Lawson, V. A. ( 1988) . Government policy biases and ecuadorian agricultural change. Annals of the Association of American G eographers 78: 433-452. Lowder, S. (1991) . Developme nt policy and its effe ct on regional inequality: The case of Ecuador. In Third World Regional Developm ent, a Reappraisal. Simon, D. (ed.), Paul Chapman Publishing., London, pp. 73-99. Mathewson, K. (1984) . Irrigation Horticulture in Highland G uatem ala: The Tabl ó n System of Panajachel . Westvie w Press, Boulder. 468 K eese Me ye r, C. A. (1993) . Environme ntal NGO s in Ecuador: An economic analysis of institutional change. The Journal of Developing Areas 27: 191-210. Nie tschmann, B. ( 1973) . Between Land and Water: The Subsistence Ecology of the Miskito Indians, Eastern Nicaragua . Seminar Pre ss, New York. Peek, P. (1980) . Agrarian change and labour migration in the Sierra of Ecuador. International Labor Review 119: 609-621. Peet, R., and Watts, M. (1993) . Introduction: Developme nt theory and environment in an age of market triumphalism. Econom ic G eography 69: 227-253. PLAN International (1994a) . Evaluaci ó n del program a de desarrollo agropecuario de la oficina de cam po Ca ñ ar Azuay. PLAN International, Quito (unpublishe d). PLAN International (1994b) . Worldwide Annual Report. PLAN International, Woking, UK. Preston, D. A. ( 1980) . Land tenure, rural emigration and rural developme nt in highland Ecuador. In Rural Habitat Transform ation in World Fron tiers. Singh, R. L., and Singh, R. P. B. (e ds.), International Centre for Rural Habitat Studies, Pub. No. 4, Varanasi, India, pp. 182-191. Price , M. ( 1994) . E copolitics and environme ntal nongovernme ntal organizations in Latin Ame rica. The G eographical Review 84: 42-58. Re dclift, M. R., and Preston, D. A. (1980). Agrarian reform and rural change in Ecuador. In Preston, D. A. (ed.), Environm ent, Society and Rural Change in Latin America. Wiley and Sons, New York, pp. 53-63. Southgate , D. ( 1990) . Deve lopment of Ecuador ’s rene wable natural re sources. In Whitaker, M. D., and Colyer, D. (eds). Agriculture & Econom ic Survival: The Role of Agriculture in Ecuador ’s Developm ent (Chap. 4) . We stview Press, Boulder, pp. 73-102. Stevens, R. D., and Jabara, C. L. ( 1988) . Agricultural Developm ent Principles: Econom ic Theory and Em pirical Evidence. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. Stewart, N. R., Belote, J., and Belote, L. (1976) . Transhumance in the central Andes. Annals of the Association of American G eographers 66( 3): 377-397. Sundberg, J. (1994) . Paradise or Prison? The Maya Biosphere Reserve, NG Os and Com m unities in the Petén, G uatem ala. Unpublished MA thesis, Departmen t of Geography, University of Te xas at Austin. Tello-Espinosa (1994) . Los e cuatorianos tienen cada ve z me nos hijos. El Com ercio ( D-1: 7/12/94) . Torres, F. ( 1994) . Director, CREA-DRI. Interview with author. Cuenca, Ecuador, December . Turner, B. L., II (1989). The spe cialist-synthesis approach to the revival of geography: The case of cultural e cology. Annals of the Association of American G eographers 79: 88-100. Whitaker, M. D., and Colyer, D. (eds) (1990) . Agriculture & Econom ic Survival: The Role of Agriculture in Ecuador ’s Developm ent. We stview Press, Boulder. Zimmere r, K. S. (1991) . Wetland production and smallholder pe rsistence: Agricultural change in a highland Peruvian region. Annals of the Association of American G eographers 81: 443-463. Zimmere r, K. S. (1993). Soil erosion and social (dis)courses in Bolivia: Perce iving the nature of environme ntal degradation. Econom ic G eography 69( 3) : 312-327.