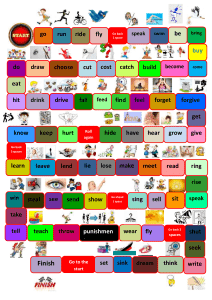

This article was downloaded by: [University of Birmingham] On: 09 October 2014, At: 19:37 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/shou19 “Soft edges” in residential streets Jan Gehl a a School of Architecture , Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts , Kongens Nytorv 1, DK‐1050, Copenhagen K, Denmark Published online: 15 Nov 2007. To cite this article: Jan Gehl (1986) “Soft edges” in residential streets, Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research, 3:2, 89-102, DOI: 10.1080/02815738608730092 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02815738608730092 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http:// www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research 3:89-102, 1986 "Soft Edges" in Residential Streets JAN GEHL School of Architecture, Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Copenhagen, Denmark Downloaded by [University of Birmingham] at 19:37 09 October 2014 Gehl, Jan: "Soft edges" in residential streets. SHPR 3:89-102, 1986. A multitude of surveys has established that life in residential streets and other public spaces is a major attraction and a very highly valued amenity. Trends in the 1980s—such as declining household size and technological changes affecting both the character and amount of work— point towards a growing importance of lively residential streets for formal and informal social activities. This article discusses a number of conditions for supporting this function of residential streets. The focus is primarily on the importance of creating "soft edges" by way of frontyards/forecourts/porches in order to provide better opportunities for staying in the public spaces for residents of all ages. Studies of residential street life in Australia, Canada, and Scandinavia are presented to support the conclusion that "soft edges" may be a most important way of promoting an active life in present-day residential streets. School of Architecture, Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Kongens Nytorv 1, DK-1050 Copenhagen K, Denmark. THE RESIDENTIAL STREET The residential street is the object for survey and discussion in this article. The reason for focussing on the residential street is the fact that it is the one basic element which can be found in almost any residential area. It provides access. It is a potentially shared space, a likely public space. As the number of persons per household declines in industrialized societies, and as residential areas tend to have still fewer other functions, such as shops, services, and workshops, the number of potential users of outdoor spaces is likewise declining. To put it in another way, there are not that many people around any more, and not that many activities generated. Thus the number of public open spaces has to be limited to ensure, at least in one place, a reasonable amount of life and social opportunities to create a shared, i.e. a public space. Thus there is a need to focus both on the streets themselves and on streets as means of supporting social life. The residential streets studied are characterized by (1) light traffic, (2) low (l-2-(3-4)) storey buildings; (3) somewhat dense building patterns of town or terraced houses (or low rise flats), and (4) by front doors facing the streets. The streets discussed then are such streets which, due to the reasonably dense low rise housing (giving easy access to outdoor areas and thus the maximum of outdoor visits per household (Bundgaard, Gehl and Skoven, 1982)), and light local traffic (Appleyard and Lintell, 1972), are most likely to function as a shared and lively public space for the residents. 90 / . Gehl Downloaded by [University of Birmingham] at 19:37 09 October 2014 LIFE IN THE RESIDENTIAL STREETS A multitude of surveys points to the fact that life and activities in streets and various types of public spaces are widely seen as an attraction and have a valued quality. In city areas, lively streets and squares are generally preferred to lifeless ones. Benches with the best view of life and activities are the most used. Children will be found playing where life and activity is at hand. Thus, "people tend to come where people are". In several Italian towns, as well as in Copenhagen, these distinctive patterns have been found in a number of independent surveys of main streets and downtown squares (Gehl, 1966, 1968 and 1980a). In New York and a number of other American cities, findings almost identical to the ones from Europe have been made by William H. Whyte and the Project for Public Spaces in New York (Whyte, 1980). As regards residential streets, surveys focussing on childrens' play patterns, use of benches, use of porches and front yards have emphasized the above conclusions that life and activities constitute an important and highly valued quality in these areas as well (Gehl, 1980 a). From the study presented here and similar studies from other residential areas, the existence of a lively residential street, a space frequently used by other people, a place where people and various activities are at hand for participation, for inspiration or just for passtive contacts—seeing and hearing—thus appears to be widely and highly valued. The opposite side of the coin—lifelessness, unsafety, isolation, boredom, no playmates, etc.—is not given a positive value. A complete range of arguments, theories and surveys emphasizing the virtues of a certain amount of life in residential streets rather than lifelessness will not be put forward—or attempted in any detail—in this context. It makes reasonable sense to let the elusive character of street life with its thousands and thousands of large and small events speak for itself. This perhaps ought to be augmented, however, by referring to a number of studies showing how feelings of territoriality and belonging can be related directly to the degree of use and life in residential streets (Appleyard and Lintell, 1972). This again is closely linked to the feeling of safety as v/ell as actual protection from violence and vandalism (Crime Prevention Board, Denmark, 1984). LU-E IN THE STREETS—A MATTER OF GROWING IMPORTANCE? N.'iturally the emphasis on life or no life in residential streets can be seen very much as a matter of ideology, of life styles and preferences. It can be argued that telecommunications, computers, TV and videos, telephones, and the like will strongly reduce the need for direct contact with other people. Thus access to lively streets and to meeting other people in one's residential area may not be of importance any more. Another set of arguments, however, will lead to a different conclusion. A number of distinctive changes in Western industrial societies point towards the SHPR 3 (1986) Downloaded by [University of Birmingham] at 19:37 09 October 2014 SHPR3O986) "Soft edges" in residential streets growing importance of access to lively spaces as a vital aspect of the contemporary residential situation. Changes in society pointing towards such a conclusion are: (a) The decline in the size of households. The average household size in Denmark has dropped from 4.7 in 1900 to 2.1 in 1985. In the cities average household size will frequently be even lower (Copenhagen 1.75)." More than half of all Danish households consist of only one or two persons. Thus a number of social functions formerly performed within households now take place outside them. (b) The changes in the age structure of the population. There are generally fewer children as a proportion of the population and fewer children in each family. Playmates—and play areas/public spaces—should thus be more accessible than previously—and houses closer together. Another change is the increasing number of elderly people. This group constitutes almost 20 percent of the population in Scandinavia and the group is characterized by having considerable amounts of free time and many years of good health and active life centered around the residential situation. No single group has been found to use public spaces and lively streets more than this expanding group of old people—provided of course that public spaces of suitable quality are available. (c) Changes in the character of working situations. A great number of people will have more monotonous, less satisfying and less creative work due to automatization and technological developments. This tends to shift the emphasis from work place to residential area for a number of creative and social activities. id) Finally, technological and other developments tend to reduce the total number of working hours needed by society. Thus time and energy are freed from the working situation and accordingly more emphasis placed on residential areas. In sum, these changes amount to the fact that more people (living in still smaller households) have more energy, resources and time available in the residential areas—where a number of social and creative needs will have to find new outlets. Deriving directly from these considerations there are more and more recommendations in Denmark regarding the need to change residential patterns towards denser housing areas with a strong emphasis on lively outdoor spaces and community buildings (Crime Prevention Board, Denmark, 1984). However, the theories, arguments and government recommendations are one thing. Quite another is to investigate whether trends in these directions can actually be found. It is reasonable to presume that various types of public spaces gain increased importance in this new situation, thus creating an empirically verifiable increase in the use of public spaces. Surveys in a number of central Copenhagen streets and squares carried out in 1968 and again in 1983 clearly show that the use of these spaces has increased markedly during the 15 years in between (though the population of Copenhagen has decreased). They are used by more people and there is a much wider range of activities. Furthermore the activities have taken an obvious swing towards more creative and expressive activities such as music, theatre, political and ideological groups, jugglers, entertainers and other performers (Gehl, 1984). 91 Downloaded by [University of Birmingham] at 19:37 09 October 2014 92 J. Gehl SHPR 3 (1986) Fig. 1. Street studies in Melbourne 1976. Design details, dimensions, and especially the opportunities for staying/sitting; in the edge zones alongside the street, were found to be major factors influencing the street life. (Brack, Gehl and Thornton, 1977.) On a smaller scale—in the local areas, the residential streets and suburban housing areas—a similar trend can be detected. The shared public spaces have been found to be extensively used in these newer areas where a good quality of the outdoor area is provided (Bundgaard, Gehl and Skoven, 1982). In this context some of the problems concerning the creation of lively residential streets will be discussed. LONG DURATION STAYS MAKE LIVELY STREETS The duration of the various activities in the residential street is by far the most important factor concerning life—or lifelessness—in the street. In this context, "life" is defined as "persons being present in the street"—a definition close to what one actually experiences: A lively street is a street with people present—a lifeless street is a street without any people in it. In this context, one person spending 30 minutes in the street will equal 30 persons each spending one minute in the street. Thus, it is not the total number of persons, but the total number of minutes spent in the streets that matters. The total number of minutes will be a product of the number of persons present multiplied by the average time spent. The main street is lively mainly because many people come there (each spending just a short time). The central square with many sidwalk cafés is particularly lively because café customers spend quite a lot of time there. Downloaded by [University of Birmingham] at 19:37 09 October 2014 SHPR 3 (1986) "Soft edges" in residential streets 93 F/g. 2. Street studies in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada 1977. The results came very close to the findings from the Australian streets. The residential street is generally characterized by the fact that only a limited number of persons live on each street and are potential users of the street. Thus with a relative low density of dwellings and few persons in the residential areas, the only way in which life in the streets can be substantially enhanced will be to emphasize the duration of the stays. Children spend time playing in the street—if the street is suitable for playing. Adults spend time in the street—if they have something to do and there are places to sit down. These factors are thus very important. Traffic, i.e. people going or driving to and from their dwellings, does not mean much in this context, because the time spent in the street is in these cases very short—20 to 30 or maybe up to 90 seconds per trip. A 1977 study of 12 residential streets with terraced or town houses in and around Waterloo, Ontario emphasizes the importance of "the time spent" in the streets as the key factor for measuring livelyness (Gehl, 1980 a, 1980 &). A direct observation study of the day-time activities in the 12 streets found that 52 percent of all activities occuring in the streets were related to traffic—coming and going—while the rest concerned people talking, staying or doing something or children playing. It was further found that the traffic activities generally are of very short duration. Parking and going into a house lasted between 20 and 30 seconds. Walking to a house only took between one and two minutes, measured as time spent in the street. Downloaded by [University of Birmingham] at 19:37 09 October 2014 94 J. Gehl SHPR 3 (1986) Fig. 3. Street A. Parking and a "nature strip" lines the street. There are hard edges alongside the houses, and virtually no activities in the street on a number of perfect summer days. The adjoining interior courtyards and the small balconies were not used either. The conclusion is that lack of quality leads to almost no activity. On the other hand, talking, staying, doing something, or playing, tended to last much longer. (Average duration of single activities was: talking 3 minutes, sta\üng 11 minutes, doing 11 minutes, playing 13 minutes.) By combining the number of persons with the time spent on the various activities it was found that 89 percent of all "life in the streets" involved talking, staying, doing and playing activities, while coming and going accounted for a mere 11 percent ofthat "life". In conclusion, life in the residential streets is thus very much a question of the residents' opportunities for staying, for doing, and for playing in the streets. Physical elements which can directly support these "long duration" activities—and thus very directly affect "life in the streets"—have been investigated in a study of 17 streets in and around Melbourne (Brack, Gehl and Thornton, 1977). Major findings from this study—based on observation techniques—were that 70 percent of all "long duration" activities encountered were found to occur in the semi-private front yards, while only 30 percent occurred on the pavements or elsewhere in the streets. Another important finding concerned the actual layout and detailing of the frontyards. Substantial differences concerning the use of frontyards were found to be clearly related to detafls in design and dimensions. Downloaded by [University of Birmingham] at 19:37 09 October 2014 SHPR 3 (1986) "Soft edges" in residential streets 95 Fig. 4. Street B parallell to Street A. Small frontyards of very useful dimensions for all the ground floor flats and a remarkably high level of activity in the street and—especially—in the frontyards. The total amqunt of activities in Street B was found to be 21 times higher than in Street A. Front yards which were too narrow or otherwise without ample opportunities for sitting were considerably less used. Thus to be useful for supporting life in the streets the front yards have to be conductive to long duration activities, a quality very well developed in the majority of Australian forecourts bordering the streets of traditional terrace houses. Taken as a whole this study strongly pointed to the semi-private front yards—the "soft edges"—as a physical element of great importance for supporting life in the streets. Further insight into these issues was gained in 1980-81 through a number of comparative studies involving comparable settings in greater Copenhagen. That survey will be exemplified by presenting two of the cases studied. TWO CASE STORIES Scene 1: Two parallel streets in a Copenhagen inner suburb Both streets were built around 1940. Both have the same types of flats, comparable rents, and comparable groups of inhabitants. Street A has buildings with 4 storeys and small balconies, while street B has buildings with 3 storeys. 96 J. Gehl SHPR 3 (1986) » PERSON ON BALCONY Downloaded by [University of Birmingham] at 19:37 09 October 2014 r i A CHILDREN • STANDING/ TALKING O SHADING O DOING X SITTING Fig. 5. Street A (above) and Street B (below). This illustration shows all people present in the two streets from a total of 20 "mappings" between 10 a.m. and 8 p.m. on a Saturday in June 1980. The importance of the frontyards in Street B as a very popular place for staying is quite evident. Downloaded by [University of Birmingham] at 19:37 09 October 2014 SHPR 3 (1986) "Soft edges" in residential streets Fig. 6. Street B. A nice summer evening by the entrance door. Children as well as grownups from the upper stories use the street much more than in Street A because Street B is much more lively and interesting. Life between the houses is a self-reinforcing process: People come were people are. The major difference between the two streets is that street B has front gardens belonging to the ground-floor flats, creating a "soft", usable edge in the public space, while street A has a "hard" edge and no opportunities for staying in the street. Both areas have interior courts. Those in street A are of appallingly poor quality, those in street B of a reasonable and useful quality. Street life in these two streets was studied simultaneously during a number of summer days in 1980 (Bundgaard, Gehl and Skoven, 1982). The techniques used were direct observations and recordings of all activities occurring in the streets, courts, and balconies from dawn to dusk. Street A with a very poor physical environment providing hardly any opportunities for outdoor stays either for children or for grownups was found to be almost deserted throughout the study days (which were really fine summer days, an opportunity seldom ignored by the Danes). The conclusion is that when the physical layout is too poor, the majority of people simply do not leave their homes, while a minority, a more energetic group go off to other areas, beaches, parks and so on. With front yards giving it a much better quality and detail, street B was found to be very lively on the very same days. All told, the activity (total number of minutes spent) in street B was found to be 21 times higher than that generated by the same number of households in street A. The more detailed findings showed 7-868802 97 Downloaded by [University of Birmingham] at 19:37 09 October 2014 98 J. Gehl Fig. 7. Hyldespjældet is a "low dense" housing area south of Copenhagen with excellent private backgardens, but no opportunities for staying outside in front of the houses. that the front gardens were widely used by adults. They spent much time there sitting, eating, reading, knitting etc., taking in the street scene and the sunshine in the process. The children (as was also found in the Australian and Canadian studies) were rarely in the front gardens. Nearly all of them were on the sidewalks and in the street proper. Furthermore, the high activity level in and around the front gardens was seen to draw quite a few people from the upper two storeys down to the street scene. Thus, "where people are, people will come". The high level of overall activity in this street was not merely caused by more people coming out into the public space, but especially by the fact that they spent much more time out there because facilities for staying and sitting were provided. This underlines the important fact that "activity" in a street is always a product of time spent and numbers present, which again underlines that life in public spaces is very much dependent on the facilities provided for staying there. The case of street A underlines that if quality is too low, no one will use the public spaces unless they have to. Coming and leaving are just about the only events occurring. The case of street B underlines the enormous difference suitable arrangements for staying can make to a street. The inhabitants of all generations are provided with a place to go and somewhere to stay. Furthermore, they can bring out their various domestic activities into the street. These opportunities were at hand in street B, and they were found to be extensively used. SHPR 3 (1986) SHPR 3 (1986) "Soft edges" in residential streets Downloaded by [University of Birmingham] at 19:37 09 October 2014 Scene 2: Two housing areas in a suburb south of Copenhagen "Hyldespjældet" and "Galgebakken" are two housing areas of the "low rise, medium density" wave of the 1970s. Both were built between 1972 and 1975. They are both public housing areas for rent, and they were inhabited at just about the same time by very comparable groups of inhabitants. Furthermore, the two areas are of comparable size and close to each other. The one striking difference between the two areas is the fact that the second area "Galgebakken" has a semi-private forecourt constituting a buffer zone between the dwellings and the public access lanes, while "Hyldespjældet" has no such facilities. Furthermore, these forecourts are very carefully designed and detailed. With most other factors as stable as can be achieved the outdoor spaces available are as follows: Hyldespjældet Park/communal green Streets and squares Access lanes Private back gardens Back lanes Galgebakken Park/communal green Streets and squares Access lanes Forecourts Private back gardens Back lanes One has the forecourts—the other has not. Would there be a difference in activity patterns in these two areas? This was the subject of another set of studies carried out simultaneously in the two areas during the summer of 1980 (Bundgaard, Gehl and Skoven, 1982). The studies were carried out over a number of days in June and August. Once more, the methods used were direct observation techniques, recording every 30 minutes the number and whereabouts of all persons being outdoors in the two areas. The main conclusions from this study were that in the area with the forecourts 35 percent more people used the outdoor areas than in the other area with the same number of households, but lacking forecourts. Furthermore it was obvious from the location of the observed activities that the reason for this marked difference was indeed the existence of semi-private forecourts in the more lively housing area. To put it in another way, the existence in one area of a more varied and better designed array of outdoor spaces—and especially the provision of a highly useful semi-private forecourt—led to a considerably higher level of activities in the outdoor areas. It was easier to leave the private dwellings and pass from the private into the public area. One striking finding about the forecourt areas was that they were used twice as much as the backyards. This indicates that given the option between staying in a secluded private backyard or staying in an open semi-private forecourt on the public side of the houses, the latter was favoured twice as often as the former. It should be noted that 50 percent of the houses face west and 50 percent face east giving equal access to sunlit back gardens and forecourts at any time. 99 Downloaded by [University of Birmingham] at 19:37 09 October 2014 100 J. Gehl Fig. 8. Galgebakken is a "low dense" housing area south of Copenhagen with excellent private backgardens as well as a very carefully designed frontyard facing the access lane. These findings indicate that many people actually appreciate being in and using the public spaces, and being in touch with life in these areas provided they are given an acceptable physical arrangement. In this study it was again evident that the edge zones with activity opportunities were used especially frequently by adults—a group which in most housing areas is neglected in terms of opportunities for staying or doing anything in the shared spaces. It is indeed interesting to note that when these opportunities were provided, they were found to be quite intensively used. It merits attention that in academic discussions the semi-private front yards have been accused of "drawing people away from the public areas and into the realm of privacy". Indeed, reality was found to be almost entirely the opposite. The existence of semi-private transition zones was found to assist the inhabitants in passing from their private homes to the public realm. The forecourts helped the inhabitants to "take the first and most difficult step" from their homes to the shared spaces. LIFE IN RESIDENTIAL STREETS Described above is a series of studies carried out in Australia, Canada and Scandinavia, all of them analysing the influence of "soft edges"—(front yards, SHPR 3 (1986) "Soft edges" in residential streets SHPR 3 (1986) Averages from 1é Counts on each of Two Saturdays in Summer 1980. Numbers outside columns represent total number of activities Numbers inside columns represent the percentage distribution of activities for each area type -^.Ch i 1 d r e n A Adults Standing Adults Sitting Adults Acting Downloaded by [University of Birmingham] at 19:37 09 October 2014 Green Area Streets and squares Entrance path 33 10 10 S t W////A 24 (4 [2 22 Front garden so Back garden Back path Entrance path Back garden •2 21 M 6 9 GALGEBAKKEN Green Area Streets and squares 59 ,Back path Fig. 9. Use of outdoor areas in Hyldespjældet and Galgebakken. HYLDESPJÆLDET porches, semi-private forecourts)—on the life in residential streets in neighbourhoods with terraced housing of low apartment houses with either light or no vehicular traffic as exemplified by the new Danish "low dense" areas. The findings from all three continents are similar. This should not be surprising, given the fact that the physical layout and detailing in the streets are—in principle—alike. In each case, the residents had access to a well dimensioned space, an area, e.g. a porch or a front yard on the street side of the houses. That this facility is found to be used in various ways cannot be surprising. Actually it would be more surprising if a number of households were each given an extra room or space, and none found any use for this facility. More interesting, however, is the finding that placing this extra space in the borderland between house and sidewalk generally seems to be a factor strengthening the life on the residential streets. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that this opportunity is primarily used by adults, i.e. groups which traditionally have very few opportunities for staying on the public side of the houses for any length of time. "Soft edges" in their various forms are thus definitely a factor of significant importance for determining the existence or no-existence of "life" in residential streets. However, it is important to point out that they only represent one among a number of factors important to life in the residential streets of the types studied. Other factors of importance would be the density of dwellings and inhabitants, the type and heights of the buildings, street dimensions, modes and intensity of 101 102 J. Gehl SHPR 3 (1986) traffic, climatic conditions, street furniture, as well as factors related to culture, lifestyles and preferences. Highlighting "soft edges" as a very important area is thus pointing to one among several important issues. On the other hand, they are a very obvious point of departure for supporting life in residential streets. Downloaded by [University of Birmingham] at 19:37 09 October 2014 REFERENCES Appleyard, D. and M. Lintell (1972) "The Environmental Quality of City Streets: The Residents Viewpoint", Journal of American Institute of Planners 38: 84-101. • Brack, F., J. Gehl and S. Thornton (1977) The Interface between Public and Private Territories in Residential Areas. Melbourne: Melbourne University. Bundgaard, A., J. Gehl and E. Skoven (1982) "Bløde kanter i boligområder—sammenfatning og konklusion" (Soft Edges in Housing Areas—Summary and Conclusion), Arkitekten 84: 421-438. Crime Prevention Board (1984) Kriminalpræventive overvejelser om miljøplanlægning. (Crime Prevention Aspects of Environmental Planning.) Copenhagen: Crime Prevention Board (Notat 13). Gehl, J. (1966) "Mennesker i Byer" (People in Towns), Arkitekten 68: 425-443. — (1968) "Mennesker till fods" (Pedestrians), Arkitekten 70: 429-446. — (1980 a) Livet mellem husene. (Life between the Buildings.) Copenhagen: Arkitektens Forlag. — (1980b) "The Residential Street Environment", Built Environment 6: 51-61. — (1984) "The Downfall and the Renaissance of Public Spaces", University of Colorado, Boulder, Proceedings, 4 Pedestrian Design Conference. Whyte, W. H. (1980) Social Life in Small Urban Spaces. Washington: The Conservation Foundation.