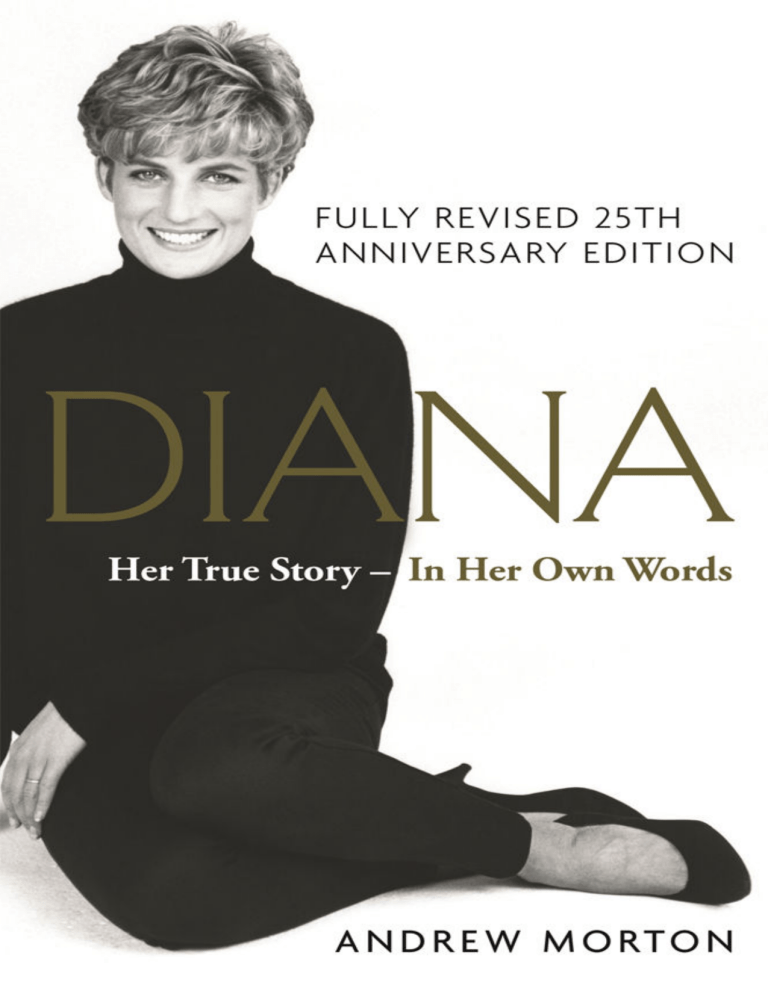

Diana Her True Story In Her Own Words 25th Anniversary Edition (1)

Anuncio