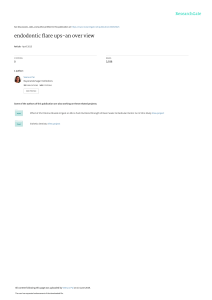

Clinical Oral Investigations https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-019-02948-3 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Effect of solvent use on postoperative pain in root canal retreatment: a randomized, controlled clinical trial Ozgur Genc Sen 1 1 & Ali Erdemir & Burhan Can Canakci 2 Received: 4 January 2019 / Accepted: 3 May 2019 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Objectives The aim of this randomized clinical trial was to assess the effect of solvent use during the removal of root canal filling on postoperative pain after retreatment. Materials and methods Ninety patients scheduled for root canal retreatment were randomly assigned to one of the following two groups according to the root canal filling removal procedure used: ProTaper retreatment (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) instruments or ProTaper retreatment instruments in combination with gutta-percha solvent. A single operator performed the retreatments in a single visit. The incidence and intensity of the postoperative pain were rated on a numeric rating scale by patients at 24, 48, and 72 h after retreatment. The analgesic tablet intake number was also recorded. Data were analyzed using Mann‑Whitney U, Wilcoxon, and chi-square tests. Results For the intensity of postoperative pain, the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant. Moreover, no statistically significant difference was found between the two groups in terms of analgesic medication intake (P > 0.05). Conclusions The processes involving the use and non-use of a solvent in the removal of root canal fillings were found to be equivalent in terms of postoperative pain intensity and analgesic intake. Clinical relevance Some in vitro studies claimed that the use of a gutta-percha solvent in the removal of root canal fillings tends to reduce postoperative pain since extrusion of debris was significantly less. This randomized clinical trial indicates that the removal of root canal fillings with or without the use of a solvent was associated with equivalent postoperative pain intensity and analgesic intake. This study is registered in the www.ClinicalTrials.gov database with the identifier number NCT03756363. Keywords Postoperative pain . Root canal retreatment . Solvent Introduction Although postoperative pain cannot be directly correlated with the long-term success of root canal treatment, its control is of great importance for patient and physician satisfaction. Retreatment is considered to be a contributing factor for postoperative complications, since it includes a number of * Ozgur Genc Sen dr.ogenc@yahoo.com 1 Department of Endodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, Van Yuzuncu Yil University Zeve Campus, Bardakci Mahallesi, 65080 Tuşpa, Van, Turkey 2 Department of Endodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, Trakya University Balkan Campus, 2213 Iskender Koyu, Edirne, Turkey laborious procedures and requires overcoming the difficulties associated with the previous root canal treatment. Removing the initial root canal filling completely is fundamental in order to perform appropriate cleaning, shaping, and obturation. During the removal of root canal filling material, guttapercha (GP), necrotic tissue remnants, dentinal chips, irrigants, and microbes may extrude from the apical foramen and gain access to periapical tissues, which may lead to postoperative complications and/or treatment failure [1, 2]. Unfortunately, all available techniques and instruments are associated with apical extrusion of debris to some degree during the root canal preparation or removal of the root canal fillings [3–8]. Several techniques such as stainless steel hand files, nickeltitanium (NiTi) rotary instruments, ultrasonics, heat-bearing instruments, and lasers have been used to remove GP from root canals [9, 10]. In combination with these procedures, Clin Oral Invest chemical solvents are recommended to facilitate the removal of gutta-percha by softening [11]. Some of the frequently investigated and used organic solvents in endodontics are chloroform, xylene, eucalyptol, halothane, orange oil, and turpentine [12–15]. Guttasolv (Septodont), a eucalyptol-based solvent, has been the choice of many professionals since it is biocompatible and safe [16]. ProTaper Universal retreatment (PTUR) instruments (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) were specifically developed for, and were proven to be effective in, removing root canal fillings [17–19]. The system consists of three progressively tapered rotary files, which have a convex triangular cross-sectional design [20]. The D1 instrument (tip 30, taper 0.09) facilitates the initial penetration into the filling material. The D2 instrument (tip 25, taper 0.08) is used for the removal of the filling material at the middle third of the canal. The D3 instrument (tip 20, taper 0.07) is used for the removal of the remaining part of the filling material up to the working length [17]. Scientific literature contains a few studies on the amount of apically extruded debris with and without the use of solvent with rotary instruments. It was reported that the use of PTUR instruments in combination with gutta-percha solvent reduced the amount of apically extruded debris compared with their use in a solvent-free process [21, 22]. Nevertheless, clinical studies on the comparison of postoperative pain after root canal filling removal with or without solvent remain to be published. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of combined use of PTUR instruments and Guttasolv solvent on postoperative pain intensity after retreatment. Materials and methods The Institutional Ethics Committee office of Invasive Clinical trials approved the protocol of this randomized clinical trial (number 13.11.2018-06). The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Before participation, all patients had read and signed an informed consent form, which describes the details, benefits, and risks of the treatment procedures. Patient selection and allocation The adult patients (18–59 years of age) who were referred to the Department of Endodontics with a diagnosis of failed root canal treatment were examined radiographically and clinically. Clinically asymptomatic, single-rooted, single-canaled teeth that had an initial root canal filling 2–4 mm short from the apex were selected. Only the teeth exhibiting radiographic evidence of well-defined periapical radiolucency (periapical index = 4 [23]) were included. Since the healing process of apical periodontitis may take up to 4 years [24], teeth in which root canal fillings were performed at least 4 years prior were selected. The exclusion criteria were as follows: patients who did not meet the abovementioned criteria; teeth with sinus tracts; teeth with intraradicular posts; teeth with overfilled root canals; presence of other teeth requiring treatments; presence of any pain disorders or systemic disease; pregnancy; utilization of antibiotics or analgesics within the last 1 month. Ninety cases were selected on the basis of the determined inclusion criteria and randomly allocated to two groups (n = 45). For a randomized selection, sealed envelopes containing group codes were placed in a bag, and a graduate student blinded to the study removed an envelope from the bag and reported the code to the physician before each treatment. Retreatment protocol A single operator completed all retreatment procedures in one session. The patients were anesthetized with 40 mg of Articain + 0.006 mg/mL epinephrine (Ultracain DS Forte; Aventis, Istanbul, Turkey). After isolation of the teeth with rubber dam, coronal restorations were removed using sterile highspeed burs until the access of the root canals become visible. The coronal 3 mm of the root canal fillings were removed using size 3 Gates-Gidden drills. Non-solvent group PTUR instruments were used in conjunction with an X-Smart electric motor (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) for the removal of root canal fillings. D1, D2, and D3 instruments were used respectively with a full rotational motion (500 rpm speed and 2 N/cm torque) until the working length was reached. Sample size calculation Solvent group The sample size calculation based on data obtained from a pilot study indicated that 38 patients would be sufficient per group (type-1 alpha error = 5%, effect size = 0.7, power = 80%). In order to compensate for possible participant dropouts during the treatment and/or follow up period, in this study, 45 patients were assigned per group. PTUR instruments were used with the abovementioned technique. However, unlike for the first group, 0.05 mL of solvent was placed in the root canal just prior to the use of D1, D2, and D3 instruments and retained for 1 min. Thus, a total of 0.045 mL of solvent was used per canal. Clin Oral Invest The working length of each tooth was determined via Propex Pixi apex locator (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) and confirmed using digital periapical radiography. When the D3 instrument easily reached the working length and no further obturation material could be seen on the instrument or in the irrigant, periapical radiography was performed to determine the completion of root canal filling removal. For final apical enlargement, #40, #45, or larger sizes (#50, #60) of stainless steel K-files were used depending on the foramen size and type of teeth. The patency of the apical foramen was verified using a #10 K-file beyond the apex. During the root canal filling removal and instrumentation procedures, 2.5% NaOCl irrigation was performed using a 30gauge side-vented syringe (Max-i-Probe; Dentsply Rinn, Elgin, IL, USA) after the use of each file. The canals were dried by aspiration and using absorbent paper points before every application of the solvent. Finally, all canals were irrigated using 3 mL 2.5% NaOCl, 3 mL 17% EDTA, 3 mL 2.5% NaOCl, and 5 mL of physiological saline solution sequentially. Thereafter, root canals were dried with paper points and obturated using a lateral compaction technique with gutta-percha cones and an epoxy resin-based root canal sealer (MM-Seal, Micromega, Besançon, France). The coronal cavities were restored using a one-step self-etch adhesive G-Premio Bond (GC Corp., Tokyo, Japan) and a hybrid composite resin (Filtek Z250, 3 M ESPE, St Paul, MN, US). Assessment of postoperative pain The degree of the postoperative pain was measured using an 11-level numeric rating scale (NRS) at 24, 48, and 72 h following the retreatment. The NRS is a segmented numeric version of the visual analog scale (VAS) and consists of successive numbers from 0 to 10 on a horizontal line. The respondent selects a number that best represents the intensity of his pain. Number B0^ represents Bno pain^ whereas number B10^ represents Bthe worst pain imaginable^ [25, 26]. A form was provided to the patients along with the NRS and they were instructed to mark the number that best reflects the sensation of pain intensity in the first, second, and third postoperative days. The patients were advised to take an analgesic tablet (400 mg Ibuprofen) in case of severe pain, at 6-h intervals. They also were requested to record the number of analgesic pills consumed each day. The forms were collected on the 4th day following the retreatment. Statistical analysis All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0 for windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations, whereas categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. The Mann‑Whitney U test was used to compare the two groups in terms of continuous variables. The Wilcoxon test was used for within-group comparisons among the different time periods. The chi-square test was performed to determine the relationships between categorical variables. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results Two patients from the non-solvent group were excluded due to the presence of pre-existing ledges that hindered access to the working length. Thus, data from a total of 88 patients were included in the statistical analysis (Fig. 1). Statistical analysis of baseline and clinical features (age, sex, tooth localization) of the non-solvent and solvent groups showed no significant differences (Table 1). Overall, within the same group, sex and tooth localization had no influence on postoperative pain for both groups. The mean NRS scores of postoperative pain at different time periods for the non-solvent and solvent groups are shown in Table 2. Differences between the two groups at all time intervals were not statistically significant. No statistically significant difference was found between the two groups in terms of analgesic medication intake (Mann‑Whitney U test, P > 0.05). In both groups, the highest NRS scores were recorded on the first day, which then decreased on the following 2 days. Statistically significant differences were found between the two groups among the time periods for each group in terms of postoperative pain intensity (Wilcoxon test, P < 0.05). In both groups, postoperative pain was comparable between the first and second days after treatment (Pnon-solvent = 0.091 and Psolvent = 0.38). The pain on the third day was significantly less than that on the first two days in the non-solvent (P3rd-1st = 0.001 and P3rd-2nd = 0.001) and solvent (P3rd1st = 0.009 and P3rd-2nd = 0.019) groups. Discussion In vitro studies have reported that solvent usage in the removal of root canal fillings result in significantly less extruded debris (compared with the non-use of solvent) and therefore could provide reduction in postoperative pain [21, 22]. Because there is no clinical evidence regarding the subject, the present randomized clinical trial aimed to determine the effect of solvent use on postoperative pain intensity in endodontic retreatments. Although higher postoperative pain values were observed in the non-solvent group compared with the solvent group, the difference was not statistically significant. The Clin Oral Invest Enrollment Assessed for eligibility (n= 185) Excluded (n= 95) Not meeting inclusion criteria (n=85) Declined to participate (n=10) Randomized (n= 90) Allocation Solvent group (n= 45) Received allocated intervention (n= 45) Non-solvent group (n=45) Received allocated intervention (n= 43) Did not receive allocated intervention (n=0) Did not receive allocated intervention (pre-existing ledge hindered instrumentation (n=2) Follow-Up Lost to follow-up (n= 0) Lost to follow-up (n= 0) Analysis Analysed (n= 43) Analysed (n= 45) Fig. 1 The CONSORT flow diagram for randomized clinical trials discrepancy of the statistical significance between in vitro extrusion studies and this study could be attributed to the presence of physical backpressure provided by periapical tissues in clinical conditions. It is also important to point out that root canals of the teeth in the abovementioned studies were obturated 1 mm short of the apical foramen, whereas the root canal filling in the present study was 2–4 mm short of the root apex. The longer distance between the root canal filling and the root apex may have induced a limited amount of material extrusion into the periapical tissues; this factor may have been the reason for Table 1 Baseline demographic and clinical features of the patients in the two groups Demographic and clinical features Gender Male Female Tooth localization Maxillary Mandibulary Mean Age (in years) Preoperative pain similar postoperative pain levels in the non-solvent and solvent groups. The obtained results indicated a low incidence of postoperative pain; this finding was consistent with those of other studies [27–29]. Moreover, this finding could be attributed to the proper procedures and adequate chemomechanical instrumentation of the root canals with maximal reduction of risk of iatrogenic and procedural errors. The working length of the root canals was determined using the Propex Pixi apex locator—the reliability of which has been documented in the literature [30]—and confirmed radiographically. The root Non-solvent n (%) Solvent n (%) P value 18 (41.5) 25 (58.1) 15 (33.3) 30 (66.7) 0.409 25 (58.1) 18 (41.9) 42 None 27 (60) 18 (40) 38 None 0.859 0.45 Clin Oral Invest Table 2 Mean postoperative pain values (mean ± SD) at the tested time periods, number of analgesic pills consumed over 3 days and p values Non-solvent (n = 43) Mean ± SD Solvent (n = 45) Mean ± SD *P value Pain on 1st day 2.33 ± 3.22a Pain on 2nd day Pain on 3rd day Analgesic intake 2.05 ± 3.27a 1.21 ± 2.57b 0.86 ± 1.92 1.44 ± 2.14a 1.22 ± 2.57a 0.64 ± 1.71b 0.40 0.14 0.34 0.47 ± 0.99 0.99 *The differences between two groups were not statistically significant (Mann‑Whitney U test, p > 0.05) a, b:↓Different lower cases represent statistically significant differences among time periods for each group (Wilcoxon test, p < 0.05) canals were instrumented in a crown-down manner using PTUR instruments to prevent apical extrusion of debris by instrumentation. [31]. Irrigation was conducted very carefully using side-vented needles. It is important to note that, despite careful fulfillment of endodontic treatment, there is always the possibility of mechanical/chemical injury to the periapical tissue [32]. Furthermore, the most promising organic solvent used for gutta-percha dissolving is eucalyptol, if the balance of the toxicity and effectiveness is considered [16, 33]. Therefore, in this study, a 100% eucalyptol-based solvent, Guttasolv, which is commonly used without causing harmful effects, was preferred. Previous studies have shown that postoperative pain is apparent during the first 2 days after root canal treatment and decreases over time [34–36]. Similarly, in our study, the pain scores for both the groups were the highest on the first day and showed a daily decrease towards the third day. Within group evaluations showed that the postoperative pain intensity of both groups was statistically similar on the first and second days, whereas it was significantly lower than those days on the third day. This statistical difference can be attributed to the fact that the pain, which tends to decrease spontaneously with time, is markedly reduced for both groups in the third day. Since pain measurement relies on patient expressions, using an easy-to-understand pain scale and questionnaire is critical for a precise pain evaluation. In this study, an NRS was used, which is reported to be a valid and reliable scale to measure pain intensity. The strength of this measure over the VAS is the convenience of administration, in both verbal and written forms, as well as the simplicity of scoring [37]. Ibuprofen is the most frequently used non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug for control of pain associated with root canal treatment because of its safety and efficacy [38, 39]. Therefore, in this study, ibuprofen was prescribed to patients to be used if required. No statistically significant difference was found between the two groups in this study in terms of analgesic intake. In the field of endodontics, a flare-up refers to the severe pain and/or swelling after root canal treatment procedures. In this study, no swelling was observed in any of the cases. Since NRS scores of 8, 9, and 10 represent severe pain, they were evaluated as flare-ups. The overall prevalence of flare-ups in this study was 12.5%. In terms of flare-up rates, the nonsolvent (13.5%) and solvent (11.1%) groups were statistically similar. These values are consistent with previously reported endodontic flare-up values of 1.4 to 16% [27, 28, 40]. These values are close to the upper limit of previously reported percentages. These high percentages may be due to the existence of more resistant infections in retreatment cases, which is suggested to be a contributing factor for postoperative complications [41, 42]. Moreover, the presence of the periapical lesions that has been reported to be a risk-enhancing factor for the development of postoperative pain may have elevated our flare-up percentages [43]. Age, sex, and tooth localization are suggested to play role in postoperative pain [44–47]. In agreement with some other studies [40, 48, 49], none of these baseline characteristics showed a significant effect on postoperative pain intensity in the current study. Furthermore, statistical analysis of the baseline clinical features (age, sex, tooth localization) revealed no significant difference between the two groups, thus showing an appropriate randomization, which minimizes the effect of these variables. Previous studies have shown a higher incidence of postoperative pain in cases with associated preoperative pain [42, 47, 50]. To eliminate the effect of this variable, in this study, only the painless cases were included. This study has some inevitable limitations because of in vivo conditions. Since each tooth has its own specific dimensions, the final apical preparation sizes could not be standardized. This may have affected the amount of apically extruded debris. Besides, endodontic retreatment involves a multistep, complex process chain, and each step has the potential to cause pain. Lastly, the different pain thresholds of the participants may have affected the pain scores. The strength of the current study lies in its design. The study was designed as a randomized controlled trial, which is accepted to be an integral part of evidence-based medicine. The guidelines of consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) statement [51] was followed for transparent and accurate reporting. To prevent bias, blinding and randomization were performed. The researcher collecting the outcome data, and the statistician and patients were blinded to the groups. Only the researcher performing the clinical procedures was not blinded and was aware of the allocated intervention immediately before the root canal filling removal (allocation concealment). Conclusion Within the study limitations, the use of a gutta-percha solvent during the removal of root canal filling did not result in a Clin Oral Invest significant reduction in postoperative pain. However, it should be considered that treatment outcome studies are required to determine the necessity or efficacy of this or any technique. Acknowledgments The authors gratefully acknowledge Prof. Dr. Sıddık Keskin for performing the statistical analysis. Compliance with ethical standards Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Ethical approval All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent Informed consent was obtained from each of the participants included in the study. References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. Siqueira JF Jr (2003) Microbial causes of endodontic flare-ups. Int Endod J 36:453–463 Seltzer S, Naidorf IJ (2004) Flare-ups in endodontics: I. etiological factors. J Endod 30:476–481 Pirani C, Pelliccioni GA, Marchionni S, Montebugnoli L, Piana G, Prati C (2009) Effectiveness of three different retreatment techniques in canals filled with compacted gutta-percha or Thermafil: a scanning electron microscope study. J Endod 35:1433–1440 Betti L, Bramante CM (2001) Quantec SC rotary instruments versus hand files for gutta-percha removal in root canal retreatment. Int Endod J 34:514–519 Bürklein S, Schäfer E (2012) Apically extruded debris with reciprocating single-file and full-sequence rotary instrumentation systems. J Endod 38:850–852 Yılmaz K, Özyürek T (2017) Apically extruded debris after retreatment procedure with Reciproc, ProTaper next, and twisted file adaptive instruments. J Endod 43:648–651 Silva EJ, Sá L, Belladonna FG, Neves AA, Accorsi-Mendonça T, Vieira VT, Moreira EJ (2014) Reciprocating versus rotary systems for root filling removal: assessment of the apically extruded material. J Endod 40:2077–2080 Caviedes-Bucheli J, Castellanos F, Vasquez N, Ulate E, Munoz HR (2016) The influence of two reciprocating single-file and two rotary-file systems on the apical extrusion of debris and its biological relationship with symptomatic apical periodontitis a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Endod J 49:255–270 Gordon MP (2005) The removal of gutta-percha and root canal sealers from root canals. N Z Dent J 101:44–52 Viducic D, Jukic S, Karlovic Z, Bozic Z, Miletic I, Anic I (2003) Removal of gutta-percha from root canals using an Nd:YAG laser. Int Endod J 36:670–673 Hülsmann M, Bluhm V (2004) Efficacy, cleaning ability and safety of different rotary NiTi instruments in root canal retreatment. Int Endod J 37:468–476 Kaplowitz GJ (1990) Evaluation of gutta-percha solvents. J Endod 16:539–540 Görduysus MO, Tasman E, Tuncer S, Etikan I (1997) Solubilizing efficiency of different gutta percha solvents: a comparative study. J Nihon Univ Sch Dent 39:133–135 14. Erdemir A, Eldeniz AU, Belli S (2004) Effect of the gutta-percha solvents on the microhardness and the roughness of human root dentine. J Oral Rehabil 31:1145–1148 15. Magalhães BS, Johann JE, Lund RG, Martos J, Del Pino FA (2007) Dissolving efficacy of some organic solvents on gutta-percha. Braz Oral Res 21:303–307 16. Pécora JD, Spanó JCE, Barbin EL (1993) In vitro study on the softening of gutta-percha cones in endodontic retreatment. Braz Dent J 4:43–47 17. Giuliani V, Cocchetti R, Pagavino G (2008) Efficacy of ProTaper universal retreatment files in removing filling materials during root canal retreatment. J Endod 34:1381–1384 18. Gu LS, Ling JQ, Wei X, Huang XY (2008) Efficacy of ProTaper universal rotary retreatment system for gutta-percha removal from root canals. Int Endod J 41:288–295 19. Takahashi CM, Cunha RS, Martin AS, Fontana CE, Silveria CF, da Silveira Bueno CE (2009) In vitro evaluation of the effectiveness of ProTaper universal rotary retreatment system for gutta-percha removal with or without solvent. J Endod 35:1580–1583 20. Ruddle C (2001) The ProTaper endodontic system: geometries, features and guidelines for use. Dent Today 20:60–67 21. Çanakçı BC, Er Ö, Dinçer A (2015) Do sealer solvents used effect apically extruded debris in retreatment. J Endod 41:1507–1509 22. Türker S, Uzunoğlu F, Sağlam BC (2015) Evaluation of the amount of extruded debris during retreatment of root canals filled by different obturation techniques. Niger J Clin Pract 18:802–806 23. Ørstavik D (1986) The periapical index: a scoring system for radiographic assessment of apical periodontitis. Endod Dent Traumatol 2:20–34 24. Ørstavik D (1996) Time-course and risk analyses of the development and healing of chronic apical periodontitis in man. Int Endod J 29:150–155 25. Rodriguez CS (2001) Pain measurement in the elderly: a review. Pain Manag Nurs 2:38–46 26. Johnson C (2005) Measuring pain. Visual analog scale versus numeric pain scale: what is the difference? J Chiropr Med 4:43–44 27. Siqueira JF Jr, Rôças IN, Favieri A, Machado AG, Gahyva SM, Oliviera JCM et al (2002) Incidence of postoperative pain after intracanal procedures based on an antimicrobial strategy. J Endod 28:457–460 28. Gama TGV, Machado de Oliviera JC, Abad EC, Rôças IN, Siqueira JF Jr (2008) Postoperative pain following the use of two different intracanal medications. Clin Oral Investig 12:325–330 29. Tsesis I, Faivishevsky V, Fuss Z, Zukerman O (2008) Flare-ups after endodontic treatment: a meta-analysis of literature. J Endod 34:1177–1181 30. Gehlot PM, Manjunath V, Manjunath MK (2016) An in vitro evaluation of four electronic apex locators using stainless steel and nickel titanium hand files. Rest Dent Endod 41:6–11 31. Al-Omari MA, Dummer PMH (1995) Canal blockage and debris extrusion with eight preparation techniques. J Endod 21:154–158 32. Haapasalo M, Udnæs T, Endal U (2003) Persistent,recurrent and acquired infection of the root canal system post-treatment. Endod Top 6:29–56 33. Chutich MJ, Kaminski EJ, Miller DA, Lautenschlager EP (1998) Risk assessment of the toxicity of solvents of gutta-percha used in endodontic retreatment. J Endod 24:213–216 34. Graunaite I, Skucaite N, Ladiene G, Agentiene I, Machiulskiene V (2018) Effect of resin based and bioceramic root canal sealers on postoperative pain: a split-mouth randomized clinical trial. J Endod 44:689–693 35. Arora M, Sangwan P, Tewari S, Duhan J (2016) Effect of maintaining apical patency on endodontic pain in posterior teeth with pulp necrosis and apical periodontitis: a randomized controlled trial. Int Endod J 49:317–324 Clin Oral Invest 36. Pak JG, White SN (2011) Pain prevalence and severity before, during, and after root canal treatment: a systematic review. J Endod 37:429–438 37. Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M (2011) Measures of adult pain. Arthritis Care Res 63:240–252 38. Kusner G, Reader A, Beck FM, Weaver J, Meyers W (1984) A study comparing the effectiveness of ibuprofen (Motrin), Empirin with codeine #3, and Synalgos-DC for the relief of postendodontic pain. J Endod 10:210–214 39. Keiser K, Byrne BE (2011) Endodontic pharmacology. In: Hargreaves KM, Cohen S (eds) Pathways of the pulp, 10th edn. Mosby Elsevier, St Louis, pp 671–690 40. Walton R, Fouad A (1992) Endodontic interappointment flare-ups: a prospective study of incidence and related factors. J Endod 18: 172–177 41. Mattscheck DJ, Law AS, Noblett WC (2001) Retreatment versus initial root canal treatment: factors affecting posttreatment pain. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 92:321–324 42. Imura N, Zuolo ML (1995) Factors associated with endodontic flare- ups: a prospective study. Int Endod J 28:261–265 43. de Oliveira Alves V (2010) Endodontic flare-ups: a prospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 110: e68–e72 44. Comparin D, Moreira EJL, Souza EM, De-Deus G, Arias A, Silva EJNL (2017) Postoperative pain after endodontic retreatment using rotary or reciprocating instruments: a randomized clinical trial. J Endod 43:1084–1088 45. Wise EA, Price DD, Myers CD, Heft MW, Robinson ME (2002) Gender role expectations of pain: relationship to experimental pain perception. Pain 96:335–342 Ertan T, Şahinkesen G, Tunca YM (2010) Evaluation of postoperative pain in root canal treatment. Agri 22:159–164 47. Arias A, de la Macorra JC, Hidalgo JJ, Azabal M (2013) Predictive models of pain following root canal treatment: a prospective clinical study. Int Endod J 46:784–793 48. Watkins CA, Logan HL, Kirchner HL (2002) Anticipated and experienced pain associated with endodontic therapy. J Am Dent Assoc 133:45–54 49. Ng YL, Glennon JP, Setchell DJ, Gulabivala K (2004) Prevalence of and factors affecting post-obturation pain in patients undergoing root canal treatment. Int Endod J 37:381–391 50. Garcia-Font M, Durán-Sindreu F, Morelló S, Irazusta S, Abella F, Roig M, Olivieri JG (2018) Postoperative pain after removal of gutta-percha from root canals in endodontic retreatment using rotary or reciprocating instruments: a prospective clinical study. Clin Oral Investig 22:2623–2631 51. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ et al (2010) CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 340:c869 46. Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.