The Monastery of Miraflores: Press Kit

Anuncio

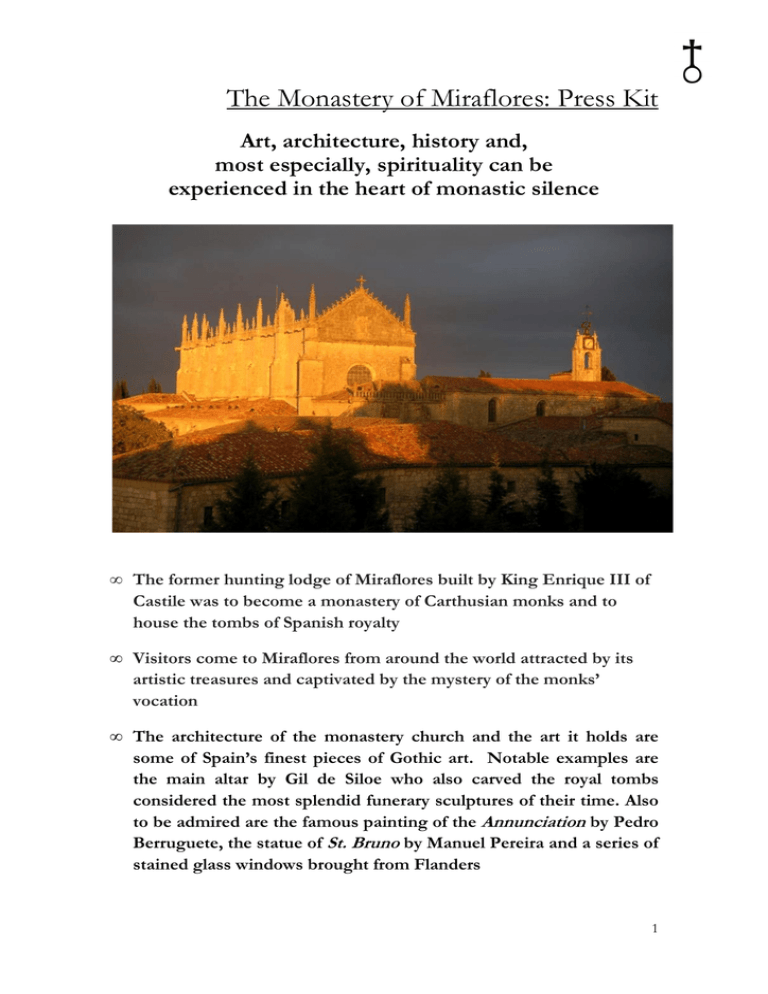

The Monastery of Miraflores: Press Kit Art, architecture, history and, most especially, spirituality can be experienced in the heart of monastic silence • The former hunting lodge of Miraflores built by King Enrique III of Castile was to become a monastery of Carthusian monks and to house the tombs of Spanish royalty • Visitors come to Miraflores from around the world attracted by its artistic treasures and captivated by the mystery of the monks’ vocation • The architecture of the monastery church and the art it holds are some of Spain’s finest pieces of Gothic art. Notable examples are the main altar by Gil de Siloe who also carved the royal tombs considered the most splendid funerary sculptures of their time. Also to be admired are the famous painting of the Annunciation by Pedro Berruguete, the statue of St. Bruno by Manuel Pereira and a series of stained glass windows brought from Flanders 1 1. More than 600 years of Art and History Known throughout Spain as the “Cartuja de Miraflores” the name “Cartuja” is the local word for a monastery of Carthusian monks. “Miraflores” is name of the hill on which it stands and could be translated as “view of flowers” referring to the lush countryside which surrounds it in the heart of the scenic park of Fuentes Blancas (“White Fountains”). Below is the Arlanzón River which, just three kilometers downstream, flows through the center of Burgos an important city on the famous medieval pilgrim route to Santiago de Compostela. Arriving here is an unforgettable moment in itself as the monastery church stands unmistakably, majestic and welcoming. Here the door is open to all who wish to discover the many treasures it holds. In 1442 King Juan II of Castile decided to donate the hunting lodge built by his father Enrique III in 1401 to the Order of Carthusian monks. They converted it into a monastery and, to the present day, it is the monks who dwell in and care for these exquisite Gothic buildings. More importantly, their hidden life of silence and solitude lends to Miraflores its unmistakable aura of peace and tranquility. From the entrance plaza three distinct parts of the monastery are clearly visible: the tall and slender silhouette of the church, the side chapels of smaller height, and the gatehouse entrance formed by three arches. The church has a single nave supported by a series of five buttresses between each of which is a magnificent stained glass window. Likewise, there 2 is a stained glass window in each of the seven sides of the apse which closes the church. The gable is in the form of a low triangle presided by the coat of arms of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabel “La Catolica”, daughter of King Juan II the founder. It was she who completed her father’s work and gave Miraflores its present form. A royal hunting lodge becomes a monastery of Carthusian monks The first monks arrived in 1442 and improvised as best they could to convert the building into a monastery. To follow them would be hundreds of monks who over the centuries have devoted their lives to God in recollection and silence within these walls. In 1452 a terrible fire reduced to ashes the greater part of the building. New plans were drawn up by the master architect Hans of Cologne but, unfortunately, King Juan II’s death in 1454 brought political upheavals to Castile. For years construction of the new monastery barely progressed. It was not until 1474 when his daughter Isabel “La Católica” succeeded to the throne that work took full momentum. Such was her interest that she is no doubt to be considered the great patroness of Miraflores as it stands today. After the death of Hans of Cologne, the architect Garci Fernandez de Matienzo briefly succeeded him in 1477. However, he died the following year and that was when Simon, son of Hans of Cologne, would step into to finish the church. 3 Queen Isabel also took a very personal interest in the decoration. A set of stained glass windows, commissioned to the famed artisan Nicolas Rombouts, arrived from Flanders in 1484. Gil de Siloe completed in 1493 two masterpieces of late Gothic art in the alabaster tomb of Queen Isabel’s parents, King Juan II and Queen Isabel, and that of her brother, Prince Alfonso. Shortly after, he began work on the high altar, a stunning and unique piece that took three years to carve. It was then polychromed by Diego de la Cruz using a technique now lost called “applied brocade” (gold leaf placed over a base of tin and then given texture and pattern by molds). In 1532 construction began on the side chapels. Finally, in 1538 the church acquired its actual appearance when, after damage caused by heavy snowfalls, a complete renovation of the roof was undertaken by Diego de Mendieta, who redesigned it adding the graceful pinnacles which give the church its distinctive profile. 2. Miraflores: an artistic and historic monument of international renown The monastery church of Miraflores with its side chapels was declared a National Monument on January 5, 1923. With a more than 600 year history Miraflores is considered a reference in Spanish culture and is visited each year by some 80,000 visitors from as many as 55 countries. About 65% of these visitors come from Spain itself of which almost a third are from the local region of Castile. 17% are from Madrid, 7% from the southern region of Andalusia and 6% from the Basque Provinces to the north. A little over half of the international visitors come from France, Italy and Germany with significant increases in visitors from other continents. Unfortunately, political upheavals of the 19th century in Spain were catastrophic for Miraflores. The monastery was sacked in 1808 by Napoleon’s troops who disbanded the community of monks and turned the buildings into a military post until forced to retreat in 1813. During those years of occupation only one monk managed to stay. It is thanks to him that, while much of Miraflores’ art was stolen, the principal pieces were respected and can be admired here today. Another heavy blow fell in 1835 when the Spanish government passed a law confiscating all monasteries with their possessions. Once again, the Carthusian monks were forced to leave their home. The lands were auctioned 4 off but as it was difficult to find a buyer and use for the buildings a handful of monks were able to continue as caretakers but forbidden to receive novices. With time the archbishop of Burgos was able to acquire ownership of the monastery ceding it to the monks in perpetual usufruct. Finally in 1880, a new political regimen permitted Carthusian monasteries in other countries to send monks to reinforce the almost extinct community of Miraflores. After some many years of bare sustenance renovation work was needed to accommodate a full community. Halfway through the 20th century, a time of abundant vocations, new repairs were made. However, entering the 21th century it was evident that a comprehensive and orderly restoration was necessary. The regional government drew up a three phase project which began in 2005 repairing first the church roof followed by that of the side chapels. Once completed it was possible to undertake the arduous and meticulous restoration of the church’s most notable works of art: the two royal tombs, the high altarpiece and the stained glass windows. Funding was provided by the Regional Government of Castile, the Archdiocese of Burgos, the local Castilian Landmark Foundation, the New York based World Monuments Fund, and the Iberdrola Foundation. More than a year and a half was necessary to complete the job but in 2007 that labor of expert artisans recovered for future generations the original beauty of these unique Gothic masterpieces. In 2009, the second phase of restoration took place in which the gatehouse courtyard was completely renovated as well as the church façade. At the same time the side chapels were refurbished to permit an ongoing exposition of paintings, sculptures and manuscripts, many of which have never before been shown to the public as they had been kept inside the monastery. The final phase is still pendant and will involve the renovation of the west wing of the gatehouse. It will house information on the life and spirituality of the Carthusian monks who over these last 600 years have given a soul and heart to Miraflores. 5 3. Principal Works of Art Royal tomb of King Juan II of Castile and Queen Isabel. Gil de Siloe. 1489-1493. Late Gothic alabaster sculpture unique for its star-shaped design. Carved with impressive skill using exquisite decoration and rich iconographic symbolism. Royal tomb of Prince Alfonso. Gil de Siloe. 1489-1493. Late Gothic sarcophagus carved in alabaster and placed within a niche on the north side of the church. The figurative motifs are superb quality and allude to the redemption of the soul. The typology used here of the kneeling figure would influence other artists throughout Castile. 6 Main Altar. Gil de Siloe. Polychrome by Diego de la Cruz. 1496-1499. Considered the finest work of Gil de Siloe, a completely innovative design of circles was adopted abandoning the traditional use of perpendicular lines. The rich and complex iconography is an expression of Faith in the Redemption brought by Jesus Christ. Stained Glass Windows. Nicolaes Rombouts. 1484. Brought from Flanders, there are in all 13 stained glass windows. The three in the apse picture scenes related to the Virgin Mary. The five on the left-hand side of the main nave represent the Passion of Christ while the matching five on the right represent the Resurrection and Glory. Noteworthy is the scene of the “Descent from Cross” as it is remarkably well conserved and signed by the glassmaker. 7 Choir of the Brohthers. Simon de Bueras. 1558. Renaissance Choir with 14 walnut stalls of marked Italian Renaissance style. In the central part of each choir stall is a saint whose life alludes to the prayer, silence and penance observed by the Carthusian monks. Choir of the Fathers. Martin Sanchez. 1486-1489. It consists of forty stalls carved in walnut with a Moorish influenced décor of geometric design. Carved in the same style are the celebrant’s chair and the lectern. To the right of the choir and immediately above the doorway is an alabaster statue of the Virgin Mary the Child Jesus, dearly invoked by the monks as “Our Lady of the Choir”. 8 The Annunciation. Pedro Berruguete. 1495-1500. This painting is considered one of the masterpieces of this artist, a Castilian native. Following formulas inspired by the Flemish style of Roger van der Weyden and the Italian Early Renaissance movement, this work reflects a careful study of light and an exquisite treatment of the central figures’ faces and robes. Saint Bruno. Manuel Pereira. 1634-1635. Baroque sculpture, one of the best preserved of this Portuguese artist. It represents St. Bruno, founder of the Carthusian monks, clothed with the traditional white habit of the Order. The ecstatic expression contemplating the crucifix is truly astonishing. 9 4. “From the Beautiful to the Divine” In order to share with visitors the monastery’s rich history and superb art, a temporary exhibition titled "From the Beautiful to the Divine” is being held in the side chapels. It is a unique opportunity to discover the impressive cultural legacy conserved for centuries with dedication and humility by the Carthusian monks inside their monastery. Floor plan of the Church with the side chapels on the north side marked in green. Here on exhibit are some of the most important pieces kept until now inside the monastery. They reflect centuries of history: such as the 15th century oil painting of the Annunciation by Pedro Berruguete, arguably the highlight of the exhibition; or another 15th century piece, the silver gilt chalice linked to King Juan II; or the royal canopy of Queen Isabel “La Católica” used when she entered the city of Burgos. Impressive as these masterpieces may be what overwhelms visitors is the deep spirituality of the Carthusian monks reflected in the splendid vestments and other liturgical pieces used daily over hundreds of years. Also on display is an important collection of book from the monastery library including manuscripts, codices, incunabula and centuries old choir books. 10 Especially worth seeing is the original text of the royal document signed by King Juan II in 1442 donating Miraflores to the Carthusian monks. Brought recently from New York is a replica of a statute of the apostle St. James, carved by Gil de Siloe for the tomb of King Juan II and Queen Isabel but whose original is now part of the collection of the The Cloisters of the Metropolitan Museum in New York. A surprise to visitors is a more modern work: a painting by Joaquín Sorolla of the Elevation of the Cross. The emotion expressed on the figures’ faces is truly astounding. These and many other impressive works of art take visitors through an unforgettable journey of art, spirituality and history. Chapel of of Our Lady of Miraflores Dedicated to the Virgin Mary, this chapel surprises visitors with its spectacular Baroque decoration. The profusion of bright colors highlights the unique iconography centered on the figure of Blessed Mother. It was Father Nicholas de la Iglesia, prior in the 17th century, who commissioned these frescos. His aim was to more worthily venerate here the statue of the Virgin nursing the Infant Jesus, one of the figures carved by Gil de Siloe for the royal tomb of King Juan II and Queen Isabel. He also collected in a book titled Flowers of Miraflores a series of devout meditations explaining the series of “hieroglyphics” or emblems painted in this chapel. Thus, we have an unusual case of a book being inspired by a piece of art. 11 5. Masterpieces of Art: taken and never returned The art to be admired at Miraflores in certainly impressive and one could easily believe that the collection is complete. Yet much has been lost over the years, basically due to the political upheavals in the 19th century. As already mentioned, when Napoleon’s army invaded Spain in 1808 Miraflores was ransacked and the buildings confiscated for military use. The occupying official, General D’Armagnac, was a man with a fine artistic taste and did not hesitate in appropriating the very best of Miraflores’ paintings for his personal collection. Among them was the St. John the Baptist Triptych by Juan of Flanders, court painter of Queen Isabel “La Católica”. Formed by five superb oil paintings on wood, they are today scattered throughout the world in different museums and private collections. Also stolen and still lost is a painting of the Adoration of the Magi, probably of Flemish origin. Perhaps the finest piece of all is a painting by Roger van der Weyden, known by experts as the Miraflores Triptych (pictured below), and now in the Staaliche Museum of Berlin. Triptych of Miraflores conserved today at the Staatliche Museum (Berlin). When in 1835 the Spanish government issued a decree suppressing monasteries, both Miraflores’ buildings and land were confiscated. This resulted in the loss of other works of art. Perhaps the most notable of these was a series of six paintings telling the life of Saint John the Baptist. Today it is in the El Prado Museum (Madrid). 12 Unfortunately, the plundering of Miraflores did not end there. In 1914, a wealthy aristocrat offered to finance some conservation work in the monastery church. He showed a keen interest in the royal tombs removing several small alabaster statues on the pretext that they were to be restored in Madrid. One of these pieces, the statue of St. James the Apostle, never returned and is now on display at The Cloisters, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York). Replica of the statue of Saint James the Apostle exhibited in one of the side chapels of Miraflores. 13 6. The Carthusian monks: nine hundred years of history and present today on three continents The beginnings of the Carthusian monks go back to the end of the 11th century. The first monastery in Spain, called Scala Dei near the city of Tarragona, was founded in 1163 followed by other foundations throughout the Iberian Peninsula: first, in the Kingdom of Aragon and later in Castile and Portugal. At the same time the Order spread throughout the rest of Europe and, more recently, to both North and South America and finally to Asia. Today it is formed by 16 monasteries of monks and 5 of nuns. Saint Bruno, the first Carthusian monk San Bruno was born in Cologne (Germany) around the year 1030. He was sent very young to pursue his studies at the famous cathedral school of Reims (France) where he would later became a prominent teacher, then a canon of the cathedral and finally chancellor of the archdiocese. He opposed the abuses committed by Archbishop Maneses guilty of simony and who would be deposed by a regional church council. The Pontifical Delegate considered Bruno a candidate to be the new archbishop of Reims; however, feeling a divine calling to hermit life he declined and set out to live totally dedicated to God in solitude and silence. So it was in 1084 that Bruno along with six companions who shared his same ideal established a hermitage is a secluded valley of the French Alps called “Chartruese”, from whence comes, in English, the name “Carthusian”. With time the form of life they initiated was canonically recognized as the Order of Hermit Monks of “Chartreuse”. Only six years after Bruno had settled in the Alps, Pope Urban II, a former student of St. Bruno in Reims, summoned him to Rome in need of his counsel. Obeying without hesitation, St. Bruno left immediately for the papal court but, as time passed, he continued to feel a call to solitude. The Pope, understanding that it was God’s will, permitted him to return to a hidden life of prayer and silence but not in Chartreuse but rather in Calabria, a region in southern Italy. That is how the second Carthusian monastery, Our Lady of the Tower, was founded and where St. Bruno would pass on to eternal life on October 6th, 1101. Today we conserve only three texts of St. Bruno whose authenticity is certain: a letter to the monks of Chartreuse written from the new monastery 14 in Calabria, a letter to an old friend and colleague in Reims Ralph Le Verd and the Profession of Faith he pronounced on his death bed. The Life of the Carthusian monks: radical commitment profound wisdom and true peace of soul Essentially, a Carthusian monk consecrates his life to prayer in silence and solitude forming a close knit community with other hermit monks. Their unique vocation is as radical as its sounds yet, in their over 900 year history, prudence and common sense have always guided them. The silence and solitude which is so characteristic of a Carthusian monastery is not a penance imposed on the monks but rather the environment they cherish and carefully nurture to better lead a life of intimacy with God. Twice each year the monks receive a visit from family and close friends but, except in very exceptional cases, no other visitors are allowed. Letters are very few and phone calls even more so. The hermitage is considered a sheltered harbor where peace, silence and joy prevail. The days are seemingly monotonous yet precisely that regularity permits the monks to free themselves of trivial concerns and focus on what is truly essential. The moments of community life foment a family like atmosphere and allow the monks to know and support each other. Together they strive to be of one heart and soul. The weekly walk and Sunday recreation are very important as they express and, at the same time, foster a community spirit. They also offer a healthy balance to the solitude which is characteristic of the Carthusian vocation. If any news from the outside world comes to a monk, he refrains from communicating it to others so as not to disturb their contemplative recollection. It is the Prior, as the monastery’s superior is called, who informs the monks on important issues of the Church, the Carthusian Order itself and, most especially, the needs of the world. Prayer is certainly the most important part of a monk’s life. Dear to them is a method of prayer called lectio divina. It involves a calm and meditative reading of the Bible. Then, in silence, one flows with the feelings of gratitude, praise or contrition that the text inspires. When inevitable distractions arise one simply returns to reading a passage of Sacred Scripture allowing it to seep into the heart. The ancient monks called this exercise “savoring” the Word of God. In the middle of the twelfth century in was precisely a Carthusian monk, Guiges, who best explained and systemized lectio divina. He classified the different movements of the soul as reading, meditating, praying and 15 contemplating. His treatise, “Scala Claustralium”, has become a classic in Christian spirituality. Basically, there are two different ways to live the Carthusian vocation. One is that of the Fathers, called so because they are priests. Their life is more enclosed in the hermitage where even their manual labor is done. The other form is that of the Brothers whose solitude is accompanied by more time spent outside their cell in the different workshops: kitchen, carpentry, tailorshop, monastery grounds and general upkeep. Both Fathers as Brothers wear the same habit and, more importantly, assist each other in living out more fully their vocation. The Midnight prayer of “Matins” and a Typical Day in the Monastery Having gone to bed at 8:00 in the evening a Carthusian monk is up again at 11:30 to prepare for the midnight prayer called “matins” followed by “lauds”. At 12:15 the bells rings inviting the monks to leave the solitude of the hermitage and join together in the monastery church. The Gregorian chant of psalms, antiphons and responses are interwoven with readings from the Holy Scriptures and the writings of the great mystics, as well as moments of total silence. Before ending around 2:15 or 2:30 (after 3:00 on Sundays and Feast days) intentions are offered for the needs of all mankind. Monks all agree that nothing like the silence of the night prepares the soul for intimate prayer. Upon returning to the hermitage there are some last prayers offered in honor of the Virgin Mary. Then the monks return to bed until 6:30 am when they rise for morning prayer and the reciting of Prima and the Angelus in preparation for the community Mass at 8:00, which is always sung. Afterwards, each of the priests celebrates Mass in solitude. Upon returning to the hermitage they recite Tercia before the morning work period. There is also time for study and spiritual reading before the midday prayer of Sexta followed by the main meal of the day at 11:30 taken in the solitude of the hermitage. Nona is prayed at 1:00 pm and then the monk returns to work and study until 4:00 when the Community again meets together in the church, this time for the singing of Vespers. Supper is at 6:00, also taken within the hermitage. About half of the year, from mid-September until Easter, this meal is reduced to only bread and wine while during the other half of the year a more generous dinner is served of vegetables with some fish or eggs. At 7:00 the bell rings reminding the monks 16 that it is time to end the day with prayer. After reciting the Angelus and Compline each monk, just before going to bed, offers his personal prayer for those he holds dearest and for the intentions of those who ask for his prayers. Special mention must be made about the deep devotion that the Carthusian monks profess to the Virgin Mary. This has been true since the very beginning of the Order. One of their many Marian traditions is to accompany the praying of the Liturgy of the Hours with what is known as the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin. Thus the example and presence of Mary brings them into the heart of Jesus Christ. The predominantly hermit lifestyle is balanced by a stronger community element on Sundays and feast days. They come together to eat in silence in the refectory and, after the midday prayers, share a time of recreation when the whole community joins to talk and enjoy one another’s company. On Monday afternoons they meet again for a long four hour walk through the fields and woods of the nearby countryside. The Handmade Craftwork of the Monks While most of the monk’s time is spent in prayer and spiritual reading, manual labor forms an important part of their day. Besides the general upkeep of the monastery each monk tends to the garden of his hermitage. They also become, each according to their skills, excellent artisans. Unique to the monks of Miraflores is the tradition of making rosaries from authentic rose petals (each rosary is made of some 3000 pressed petals). They also make candles of pure beeswax and small plaster figures of monks in prayer. The sale of these and other items at the monastery gift-shop help the monks support themselves. 17 Annex 1: Important Dates in the History of Miraflores. The monastery church of the Cartuja de Miraflores, 1847. Print by Domingo de Aguirre 1401 The original building, a hunting lodge, is constructed on top of Miraflores Hill by King Enrique III of Castile. 1442 The Carthusian Monks officially accept the donation of Miraflores by King Juan II of Castile and convert the buildings into a monastery. The original title of Saint Francis is respected. 1452 A fire reduces the building to ashes. The title is change to Our Lady of the Annunciation. 1454 Master architect Hans of Cologne draws up blueprints following the traditional distribution of a Carthusian monastery. On June 22, King Juan II dies in Valladolid. 1455 Following his last wishes, the remains of King Juan II are taken to Miraflores as his final resting place. 18 1468 Juan II´s son, Prince Alfonso, dies in Cardeñosa, province of Ávila, on July 5th. His remains will later be taken to Miraflores for his final burial. 1474 Upon the death of King Enrique IV of Castile, his half-sister Isabel, later to be known as “la Católica” succeeds to the throne. She will be Miraflores’ great patroness. 1477 Hans of Cologne dies. Matienzo Garci Fernandez assumes the work of master architect. A year later he himself dies leaving the walls of the church completed. Construction continues under Simon, son of Hans of Cologne. 1483 Queen Isabel visits her father´s tomb and takes a personal interest in finishing the church. 1484 Martin de Soria, a Burgos merchant, brings a set of stained glass windows from Flanders that had been commissioned by the Queen Isabel to decorate the church. 1486 Gil de Siloé begins the first sketches of the royal tombs. The main façade of the church is finished. 1488 The vaulting of the church is completed. 1489 Martin Sánchez carves the stalls of the Fathers’ Choir. 1489-1493 Gil de Siloé sculpts the royal tombs. 1492 The remains of Prince Alfonso, son of Juan II and brother of Queen Isabel “la Católica”, are brought to Miraflores and placed in the tomb prepared on the Gospel side of the church. 1496 Isabel of Portugal, second wife of Juan II, mother of Queen Isabel “la Católica” and Prince Alfonso, dies on August 15th in the castle of Arévalo, province of Ávila. In 1505 her remains will be moved to the royal tomb prepared at Miraflores. 1496-1499 Gil de Siloé carves and Diego de la Cruz paints the main altar. 1504 Queen Isabel “la Católica” dies on November 26th in Medina del Campo, province of Valladolid. 1506 Death of King Philip the Fair, married to Queen Juana “la Loca”. The Miraflores church is used as the funeral chapel until several months later his remains are taken to Granada. 19 1532-1539 A series of side chapels are added on the north side of the church. 1538-1539 After damage due to unusually heavy snowfalls, Diego de Mendieta rebuilds the church roof adding the pinnacles and an elaborate parapet. 1558 Simón of Bueras carves the stalls of the Brothers’ Choir. 1657-1659 Reform work is done on the church according to the Baroque spirit. A chapel is constructed behind the main altar in which the Carthusian monk Cristobal Ferrando paints part of the murals. At this same time Polycarpo de la Nestosa and Bernardo Elcarreta carve the ornate altars in the Brothers’ Choir. The main façade is moved from the north side to the foot of the church on the west side. 1808 Napoleon invades Spain. Miraflores and almost all other monasteries are suppressed. Some of the monks from Miraflores are able to join the Carthusians of the El Paular monastery near Segovia but are soon forced to disperse. Having been ransacked Miraflores is used as a military outpost. 1814 King Fernando VII decrees the restoration of monasteries. The Carthusian monks return to Miraflores. 1820 A new suppression of monasteries is decreed, this time by the Spanish government. Miraflores becomes State property. As before, some monks from Miraflores find refuge at the El Paular monastery. 1821 Miraflores is assaulted by a radical group from Burgos. Among other damage, the crown and scepter of the King Juan II’s statute are smashed. 1823 Restoration of monasteries: the Carthusians return to Miraflores but recover only a part of their property. 1835-1836 Yet another decree of extinction of monastic Orders is issued. Miraflores, once again, is confiscated as state property. Some monks of Miraflores go into exile finding refuge in Carthusian monasteries in France. 1845 Minor repairs: part of the church is paved, the wrought iron grill protecting the royal tombs is redone and the walls of the church are whitewashed. 20 1864 Most Reverend Fernando de la Puente, Archbishop of Burgos, acquires ownership of Miraflores from the government. 1880 The monastery is ceded to the Carthusian Orden by the archdiocese of Burgos. As only two elderly monks have survived the confiscation of 1835 a group of young Carthusians is sent from France. 1914 Reform work in the gatehouse. 1931 Extensive repair work is done on the church roof. 1952 Part of the gatehouse is adapted to assure the solitude of the monks. The rooms reserved for the visits of family members are refurbished. 1965 Repair work is done on the roof of the side chapels. 1967 A new brick floor is put down in the side chapels. 1969 The stone pavement of the church is renovated. 1974 The rotted wooden beams of the church roof are replaced by ones of cement. 1975 A series of restoration work is begun in the church atrium, the gatehouse courtyard and the rooms for visitors. 2003-2006 Restoration is undertaken of the stained glass windows. 2005 Repair work is done on the church roof. 2005-2007 A complete restoration is undertaken of the royal tombs, the main altarpiece and the murals in the chapel behind the main altar. 2006 Restoration of the side chapels. 2009-2010 The gatehouse cloister is restored. The church façade is restored and three of the side chapels are renovated for exhibitions. 21 Annex 2: Principal Artists who worked at Miraflores Pedro Berruguete: born in Paredes de Nava, in the neighboring province of Palencia, he may have travelled to Italy to learn the Renaissance style. As of 1483 documents speak of the paintings he was commissioned by royalty and high church dignitaries. Having worked throughout Castile the Annunciation he painted for Miraflores is thought to be one of his later and perhaps finest works. Hans of Cologne: one of the most prominent figures in the history of Miraflores as he was the architect who designed the church and monastery after the great fire of 1452. He was also a key figure in Castile as it was he who introduced the German style of late Gothic architecture as can be seen in the spires of the Burgos Cathedral. Simon of Cologne: son of the original architect Hans, he took over construction when Matienzo Garci Fernandez died in 1478. He completed the vaulting of the church in 1484. Among his best known works is the chapel of the Condestables in the Cathedral of Burgos. Diego de la Cruz: Spanish painter of Flemish influence who worked principally in Castile at the end of the 15th century. His extraordinary skill can be appreciated today in the exquisitely polychromed altarpiece of Miraflores. Simon Bueras: From the northern coast of Spain, he began to work as a sculptor in the Burgos Cathedral around 1550. In Miraflores, he carved in fine walnut the Brothers’ choir in 1558. The stalls have a strong Renaissance style with figures of saints and hermits, in perfect harmony with the life of prayer and solitude of the Carthusian monks. Garci Fernandez de Matienzo: appointed in 1477, he was the second architect of Miraflores and would die of the plague the following year. In any case, only recently had construction resumed in earnest thanks to generous support of Queen Isabel “La Católica” who had ascended the throne in 1474. This circumstance gave Garci Fernandez de Matienzo the possibility of completing the walls of the church. Juan of Flanders: Of Flemish origin, he was court painter to Queen Isabel “La Católica” and considered one of the most important artists of late 15th century Spain. He was commissioned to paint an altarpiece with scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist for the Miraflores church. This superb 22 masterpiece has permitted experts to study his style during his first years in Castile. Unfortunately, the paintings disappeared when Napoleon’s troops plundered Miraflores in 1808 and today are scattered among museums and private collections. Diego de Leyva: Prolific painter from Haro, province of La Rioja, born in 1580 and known for his religious themes of martyrs, saints and virgins. After the death of his wife he entered Miraflores and became a Carthusian monk at the age of 53. Although he continued to paint few of his works have remain today at Miraflores due to due to the confiscation and looting suffered during the first half of the 19th century. Diego Mendieta: A 16th century architect who gave the Miraflores church its distinctive silhouette when he repaired the roof. He raised the height of the walls and decorated the roof with a series of pinnacles and a graceful parapet. Manuel Pereira: A Portuguese sculptor was won great fame in the royal court of Madrid in the 17th century. There is an often told story about the visit King Felipe IV made to Miraflores. One of the courtiers admiring the expressive features of the statue of St. Bruno carved by Pereira said to the king: "it need only to speak". The King is said to have replied, "he won’t speak because he´s a Carthusian". Nicolaes Rombouts: From Flanders, he was one of the Europe’s most famous stained glass artisans in the late fifteenth century. Unfortunately, little of his production has survived. This gives the windows of Miraflores a particular importance as they are most complete and best preserved of his works. Martin Sánchez: Sculptor of the Fathers’ choir stalls which he finished in 1489 and is considered one of the masterpieces of its genre. Gil of Siloé: Perhaps of Flemish origin, he was undoubtedly one of the finest sculptors of late 15th century Castile. His expertise in detail is evident in the high altar and the royal tombs of Miraflores. Roger van der Weyden: An apprentice of Robert Campion and contemporary of Jan van Eyck, he was one of the most famous and influential painters of the Flemish school in the mid-15th century. In the oil painting known today as the "Miraflores Triptych", now part of the Staatliche Museum collection in Berlin, he achieved a remarkable expressiveness. Queen Isabel 23 “La Católica” was so impressed by this work that she had her court painter Juan of Flanders make a copy for the Royal Chapel of the Granada cathedral. 24