The Feminist Revolution

Anuncio

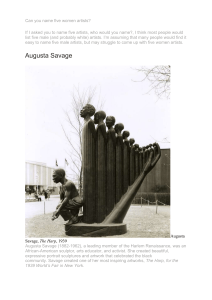

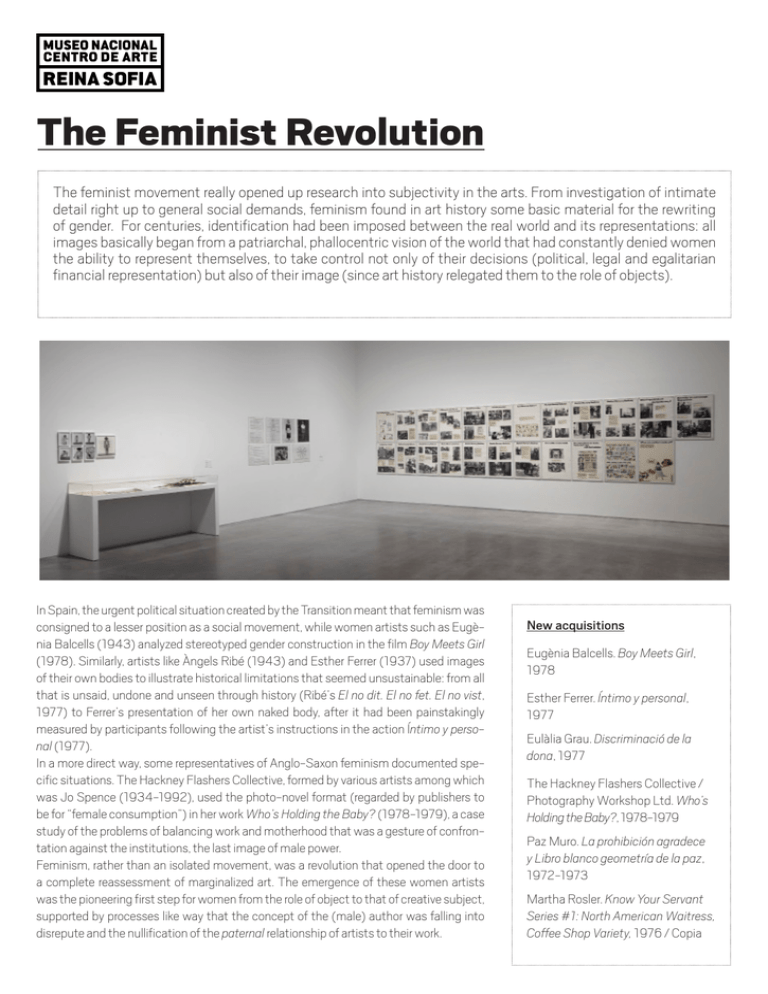

The Feminist Revolution The feminist movement really opened up research into subjectivity in the arts. From investigation of intimate detail right up to general social demands, feminism found in art history some basic material for the rewriting of gender. For centuries, identification had been imposed between the real world and its representations: all images basically began from a patriarchal, phallocentric vision of the world that had constantly denied women the ability to represent themselves, to take control not only of their decisions (political, legal and egalitarian financial representation) but also of their image (since art history relegated them to the role of objects). In Spain, the urgent political situation created by the Transition meant that feminism was consigned to a lesser position as a social movement, while women artists such as Eugènia Balcells (1943) analyzed stereotyped gender construction in the film Boy Meets Girl (1978). Similarly, artists like Àngels Ribé (1943) and Esther Ferrer (1937) used images of their own bodies to illustrate historical limitations that seemed unsustainable: from all that is unsaid, undone and unseen through history (Ribé’s El no dit. El no fet. El no vist, 1977) to Ferrer’s presentation of her own naked body, after it had been painstakingly measured by participants following the artist’s instructions in the action Íntimo y personal (1977). In a more direct way, some representatives of Anglo-Saxon feminism documented specific situations. The Hackney Flashers Collective, formed by various artists among which was Jo Spence (1934-1992), used the photo-novel format (regarded by publishers to be for “female consumption”) in her work Who’s Holding the Baby? (1978-1979), a case study of the problems of balancing work and motherhood that was a gesture of confrontation against the institutions, the last image of male power. Feminism, rather than an isolated movement, was a revolution that opened the door to a complete reassessment of marginalized art. The emergence of these women artists was the pioneering first step for women from the role of object to that of creative subject, supported by processes like way that the concept of the (male) author was falling into disrepute and the nullification of the paternal relationship of artists to their work. New acquisitions Eugènia Balcells. Boy Meets Girl, 1978 Esther Ferrer. Íntimo y personal, 1977 Eulàlia Grau. Discriminació de la dona, 1977 The Hackney Flashers Collective / Photography Workshop Ltd. Who’s Holding the Baby?, 1978-1979 Paz Muro. La prohibición agradece y Libro blanco geometría de la paz, 1972-1973 Martha Rosler. Know Your Servant Series #1: North American Waitress, Coffee Shop Variety, 1976 / Copia Bibliography Aliaga, Juan Vicente. Orden fálico. Androcentrismo y violencia de género en las prácticas artísticas del siglo XX. Madrid: Akal, 2007. Aliaga, Juan Vicente (ed.). A voz e a palabra. Coloquio sobre A batalla dos xéneros. Santiago de Compostela: CGAC, 2008. Butler, Judith. Cuerpos que importan. Sobre los límites materiales y discursivos del “sexo”. Buenos Aires: Paidós, 2002. Chadwick, Whitney. Mujer, arte y sociedad. Barcelona: Destino, 1992. Mayayo, Patricia. Historias de mujeres, historias del arte. Madrid: Cátedra, 2003. Nochlin, Linda. “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists”. Art News, vol. 60, 1971. Pollock, Griselda. Generations and Geographies in the Visual Arts: Feminist Readings. Nueva York: Routledge, 1996. Reckitt, Helena; Phelan, Peggy, Art and Feminism. Londres: Phaidon, 2001. Links http://www.mav.org.es/ http://www.moca.org/wack/ http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/ eascfa/feminist_art_base/