Design and implementation of community-based breeding

Anuncio

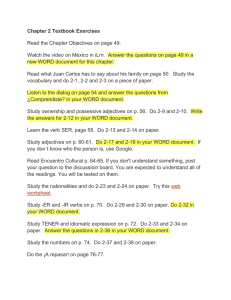

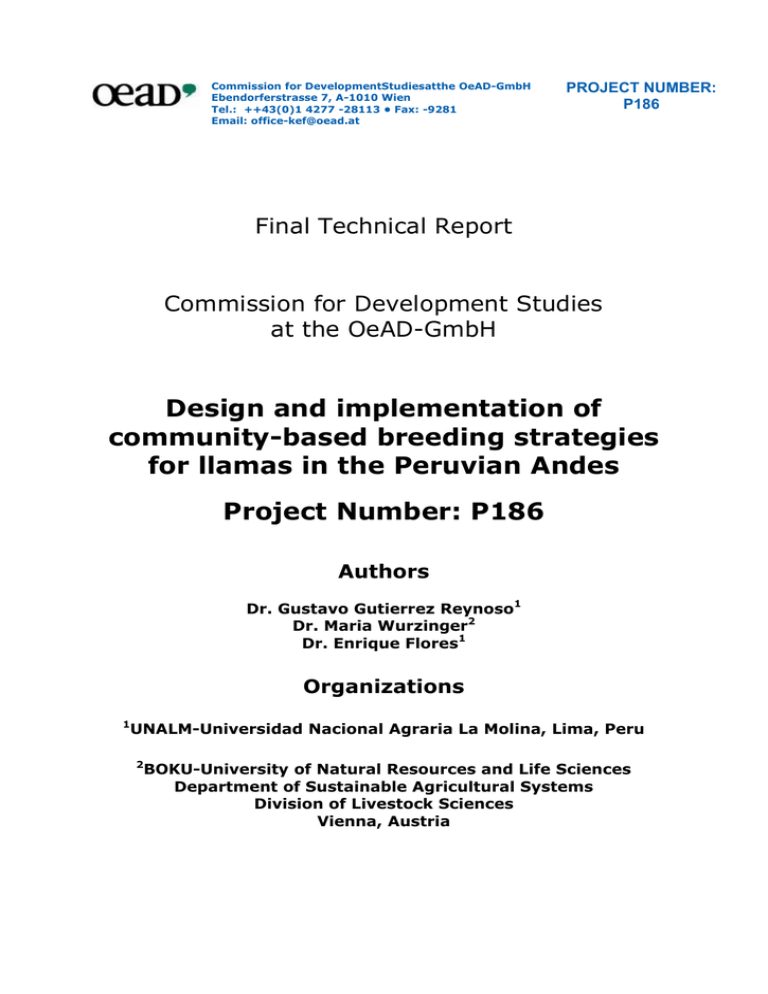

Commission for DevelopmentStudiesatthe OeAD-GmbH Ebendorferstrasse 7, A-1010 Wien Tel.: ++43(0)1 4277 -28113 • Fax: -9281 Email: office-kef@oead.at PROJECT NUMBER: P186 Final Technical Report Commission for Development Studies at the OeAD-GmbH Design and implementation of community-based breeding strategies for llamas in the Peruvian Andes Project Number: P186 Authors Dr. Gustavo Gutierrez Reynoso1 Dr. Maria Wurzinger2 Dr. Enrique Flores1 Organizations 1 UNALM-Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Lima, Peru 2 BOKU-University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Department of Sustainable Agricultural Systems Division of Livestock Sciences Vienna, Austria Design and implementation of community-based breeding strategies for llamas in the Peruvian Andes Project Number: P186 Index Abstract Zusammenfassung 1 Introduction 2 Objectives of the project 3 Expected Outcomes 4 Study sites 5 Achieved aims and results Outcome 1. Characterization of production systems Outcome 2. Phenotypic characterization of three llama populations Outcome 3. Breeding strategies and social networks Outcome 4. Design and implementation of breeding strategies 6 Scientific publications and publications in local media 7 Theses 8 Follow-up of project activities Annexes 2 Abstract The main goal of this research was to characterize the llama production systems and llama populations in three locations of the Peruvian Central Andes and to develop and to implement jointly with the owners a breeding program for a sustainable use of the local llama populations. This study was a joint effort between Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina-UNALM (Peru) and BOKU University (Austria). The study sites have been Marcapomacocha (Junín), Huayllay (Pasco) and San Pedro de Racco (Pasco). Detailed information about the importance of llama rearing, current management practices and breeding strategies have been collected through individual household interviews and the data has been crosschecked and validated in workshops with key informants. A total of 126 smallholders were interviewed. Results indicate that the llama production system is based on natural pasture, and rangelands belong to peasant communities. Herds are mixed and composed of llamas, alpacas, sheep and cattle. The average size of llama herds is 35 animals. Llama Kara, which is a meat-oriented type, is the most common type in all three study sites. Only 44% of farmers practiced selection for both males and females. The selection criteria are height, conformation and colour. The mating system is not controlled. In most cases, replacement animals come from the own herd. All interviewees said that they would like to continue with llama rearing in the future. The majority of the farmers indicated that they would like to increase the herd sizes as llamas are more resistant and robust than alpacas. A phenotypic characterisation of the llama population was performed. Data from 1071 llamas were collected for height at withers, thoracic circumference, thigh volume, rump area, cannon bone circumference and body weight in the three study sites. Llamas of the region are taller and heavier than llamas from the South of Peru. High phenotypic variation in the traits measured was observed. That indicates that selection may be feasible, but there is a need for estimating genetic parameters such as heritability and genetic correlations of traits form the study population. Results were shared with farmers and local authorities, and a multi-stakeholder consultation process was performed in each region for the design of a community-based breeding program. This involved personal interviews with farmers, but also a series of workshops with farmers, representatives of local government, an NGO and universities. These platforms were used to distribute information on breeding programs, but also to discuss and agree on level of involvement, roles and responsibilities of different stakeholders in a breeding program. In Pasco, a llama breeders association was formed and is officially recognised by local institutions. Alternative breeding strategies, such as central versus dispersed nucleus, were presented and discussed with farmers. This participatory approach with the involvement of different actors ensures commitment and ownership of all parties which is a pre-requisite for the longterm sustainability of a breeding program. Students from both partner universities got the opportunity to carry out research for their theses. One master student from BOKU-Austria completed her thesis, 3 and five master students and one doctoral student from UNALM-Peru are currently analysing data and writing their theses under the supervision of the project coordinators. 4 Zusammenfassung Ziel des Projekts war es sowohl die Produktionssysteme als auch die Lamapopulationen in drei verschiedenen Regionen in den Anden in Zentralperu zu charakterisieren. Aufbauend auf diesen Ergebnissen wurden mit den LandwirtInnen Zuchtprogramme entwickelt und implementiert. Die Studie wurde von der UNALM-Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina in Peru und der BOKUUniversität für Bodenkultur durchgeführt. Die Studie wurd in Marcapomacocha (Junín), Huayllay (Pasco) und San Pedro de Racco (Pasco) durchgeführt. In Einzelinterviews mit Bauern und Bäuerinnen wurden Informationen zu folgenden Themenbereichen erhoben: Bedeutung der Lamahaltung, gegenwärtiges Herdenmanagment und Züchtungsstrategien und zukünftige Trends . In Gruppendiskussionen wurden die Ergebnisse erörtert und validiert. Insgesamt wurden 126 Interviews durchgeführt. Ergebnisse zeigen, dass die Haltung vorwiegend auf kommunalem Weideland passiert. Die Betriebe halten gemischte Herden, die sich aus Lamas, Alpakas, Schafen und Rindern zusammensetzten. Im Durchschnitt werden 35 Lamas auf einem Betrieb gehalten. In allen drei Studiengebieten wurden hauptsächlich Lamas vom Typ „Kara“ gehalten. Dieser Typ wird für die Fleischproduktion verwendet. Nur 44% der Befragten gaben an, dass sie sowohl bei den männlichen als auch bei den weiblichen Tieren Selektion betreiben. Selektionskriterien sind Größe, Körperbau und Vliesfarbe. Tiere für die Bestandserneuerung werden fast ausschliesslich aus dem eigenen Betrieb nachgestellt. Alle Befragten gaben an, dass sie auch in Zukunft Lamas halten möchten. Eine Mehrheit möchte die Herden sogar vergrößern, da sie finden, dass Lamas widerstandskräftiger und robuster als Alpakas sind. Für die phenotypische Charakterisierung wurden insgesamt 1071 Lamas gewogen und vermessen. Maße wie Widerristhöhe, Brustumfang, Volumen des hinteren Oberschenkels, Fläche der Kruppe und Umfang des Sprungbeins wurden erhoben. Lamas in den Studiengebieten sind deutlich größer und schwerer als Tiere im Süden Perus. Eine hohe phenotypische Variation konnte in allen gemessenen Merkmalen beobachtet werden. Dies ist ein Indikator, dass eine Selektion auf bestimmte Merkmale möglich ist. Hierfür ist aber eine Schätzung genetischer Parameter wie Heritabilität und genetische Korrelationen zwischen verschiedenen Merkmalen erforderlich. Alle Ergebnisse wurden sowohl den Bauern und Bäuerinnen als auch den lokalen Behörden vorgestellt. Unterschiedlichste Akteure und Vertretungen von Interessensgruppen wurden kontaktiert, um ihre Ideen zur Implementierung eines Zuchtprogramms zu erheben. Es wurden Einzelinterviews durchgeführt und workshops mit Bauern und Bäuerinnen, Vertretern der lokalen Regierung, VertreterInnen von NGOs und MitarbeiterInnen von Universitäten durchgeführt. Diese Treffen wurden als Informations-und Diskussionsplattformen genutzt. Es wurden die unterschiedlichen Rollen, Aufgaben und Funktionen unterschiedlicher Personen(gruppen) in einem Zuchtprogramm diskutiert. Alternative Züchtungsstrategien wie zentraler oder dezentraler Nukleus wurden vorgestellt und Vor-und Nachteile erläutert. In Pasco entschieden sich die LamahalterInnen eine Zuchtorganisation zu gründen, die auch von offizieller Seite anerkannt wird. 5 Dieser partizipative Prozess und die Einbindung aller Akteure kann das Engagement und die Eigentümerschaft aller Beteiligten besser garantieren. Dies ist eine wichtige Voraussetzung für eine langfristige und nachhaltige Entwicklung des Zuchtprograms. Studierende von beiden Universitäten konnten im Rahmen des Projekts Daten für ihre Abschlussarbeiten erheben. Eine Masterstudentin der BOKU hat bereits ihre Arbeit abgeschlossen, fünf Studierende im Master „Nutztierwissenschaften“ an der UNALM und ein Doktorand sind gerade dabei ihre Arbeiten abzuschließen. 6 1 Introduction Llamas (Lama glama) are one of the domestic south American camelids which are reared in the rangelands of the Andean Highlands. The Peruvian llama population counts about 1,006,614 heads (FAO, 2005) and remains stable over the last years, but is smaller than other livestock species such as alpaca and sheep which are also kept in the Highlands. However, llamas are traditionally kept in higher altitudes under extremely harsh conditions where agriculture is not feasible (Ruiz et al., 2004). This is possible as llamas are well-adapted to live in high altitudes and use efficiently native grasses (Gutierrez, 1993). Llamas are a valuable genetic resource because of their adaptation to harsh weather conditions, their ability to better utilize the limited and poor quality native grasses, their lower needs of water and dry-matter, and their ability to provide goods (meat, fiber) and services (transportation) in low-input systems. Therefore, llama husbandry is the only economic and ecological way to use these rangelands. Moreover, llamas provide food and income to peasants. Fiber and meat production is estimated to be about 0.7 and 4.0 thousand tons per year, respectively (Ministerio de Agricultura, 2010). About 94,170 families are involved in lama production in Peru (Censo Nacional Agropecuario, 1994), mostly living in extreme poverty, depend on this activity. Most llama farmers are smallholders, thus the average herd size is 10.7 heads, and 89% of families have less than 100 hectares of rangeland. Migration to Lima or other areas of Peru is a serious problem. From 1997 to 2007, the rural population decreased by 4.5%. Only elderly people remain on the farm. Therefore finding alternative income strategies for rural families is important in order to work against the migration trend to urban centers. There is in general a lack of research done in Peruvian llamas, more emphasis is given to alpaca. Most of the research in llamas was done in the southern region of Peru. The areas of research were reproduction, animal health care, fiber and meat production, processing and marketing (i.e. Maquera, 1991; Caceres, 2002; Ruiz et al., 2004; FAO, 2005, Siguayro, 2010). Unfortunately, little attention has been given to know current breeding strategies, and setting up realistic and optimum breeding goals for their genetic improvement. As a result llama population is endangered and, unless urgent concerted efforts are made to characterize and manage, it may be lost. The farming system in the Peruvian Highlands is threatened by the global phenomena climate change. Reduced availability of water and unpredictable rainfall patterns are possible threats to the farmers. This will result in fewer options for agricultural activities and a higher importance of livestock rearing. Llamas have the comparative advantage over alpaca and sheep to better deal with water scarcity and lower feed quality. As a result, providing llama producers with the technology and a well-designed breeding program may be a key to increase the level of competitiveness and sustainability of their farming systems and reduce the migration to urban centers. 7 2 Objectives of the project The main goal of this research is to characterize the llama production systems and llama populations in three locations of the Peruvian Central Andes and to develop and to implement jointly with the owners a breeding program for a sustainable use of the local llama populations. Specific objectives: - Characterization of the production systems in three locations - Phenotypic characterization of llama populations, including productive and reproductive performance - Documentation of current breeding strategies, networks for the exchange of breeding stock - Development and implementation of improved breeding strategies for a sustainable use of llamas including the social 3 Expected Outcomes At the end of the project all expected outcomes were accomplished. Expected outcomes Current production systems Planned month Actual month 6 4 6 8 6 8 18 17 18 18 18 18 characterized Phenotypic characterization of three llama populations completed Breeding strategies and social networks documented Improved breeding strategies developed Improved breeding strategies implemented Publications in local media and scientific publications produced 8 4 Study sites The study was performed in three sites located at the highlands of the Peruvian Central Andes (Table 1, Figure 1). The largest llama population in the region is found in these sites and counts approximately 52 000 animals. Latitude and longitude of the study sites range between 10S to 12S and 76W to 77W, respectively. Annual rainfall varies from 800 to 1200 mm per year, but it is concentrated in the wet season (October-April). The mean annual temperature is less than 10 °C with frost occurring at early morning mainly in the dry season. Mountain rangeland is the predominant landscape; vegetation is composed mainly by native grasses and forbs. Table 1. Characteristics of study sites Zone Sites Region Altitude (masl) 1 Marcapomacocha and Sangrar 2 Huayllay (San Canchacucho, Carlos, Main activity Junin 4330 Livestock Huarimarcan, Pasco 4200 Livestock, Condorcayan, La Mining Cruzada, Leon Pata, and Andacancha) 3 San Pedro de Racco, Rancas, Santa Ana Pasco de Tusi, Quiulacocha, Ucrucancha, 4400 Livestock Sacrafamilia, Tunacancha, and Racracancha Figure 1. Map of study regions fg ZONE 3 ZONE 2 ZONE 1 9 5 Achieved aims and results Following the outline of the project proposal the achieved aims and results are presented. Outcome 1. Characterization of production systems Activity 1. Baseline survey A first visit to all study areas was done and the proposed research was discussed with the local authorities and llama keepers (June and September 2011). In order to promote the participation of llama keepers in the project, one workshop was held in San Pedro de Racco (June, 2011), and other in Marcapomacocha (September 2011). To serve the same purpose, a course on llama health care was held in Marcapomacocha (October 2011). Furthermore, the local team met twice local authorities of Huayllay to explain the project goals and activities (June 2011). As the official start of the project was delayed, UNALM and BOKU funded the first field visits in order not delay the start of the field data collection. The team was worried that data collection during rainy season, which starts in October might lead to problems in data collection in the field. A survey using a semi-structured questionnaire was applied. A total number of 126 individual households (22 in Zone 1, 38 in Zone 2, and 66 in Zone 3) participated in this activity. The survey was carried out in the first four months of the project. The questionnaire covered various topics such as socio-economic situation of the households, importance of livestock production, herd management, pasture management, marketing of products and external support from different agencies. Details about breeding practices and local strategies of exchange of breeding animals were collected to get a first insight into the social networks of the smallholders in the region. All data has been entered into EXCEL and quantitative information has been analysed using EXCEL and SAS. Activity 2. Series of workshops Two workshops in Marcapomacocha (March and June 2012) and two in Cerro de Pasco (June and September 2012) were organized in order to inform llama keepers about the preliminary results of the project and to perform a SWOT analysis and to discuss possible strategies for improving llama husbandry in the three locations. The workshop of Cerro de Pasco (June 7, 2012) was attended by 43 farmers from Zone 2 and Zone 3. A verification check of obtained results was made. After a brief introduction of the concept of community-based breeding strategies, a discussion about possible forms of collaboration were discussed. The farmers agreed to form an organization committee to organize follow-up meetings to discuss the formation of an Association of llama keepers. The representative of the Ministry of Agriculture is member of the committee in order to ensure links to the official policies of the country. One NGO called “Asociación Fomento y Promoción para el Desarrollo Andino" (FODESA) was identified as a collaborator as this NGO has currently a project with the goal 10 to improve livelihoods of smallholder farmers with llamas. Llama breeders association representatives were elected on September 29th, 2012. A similar workshop with 15 farmers was held in Marcapomacocha on June 9, 2012. The community discussed different forms of collaboration and agreed to discuss this point more in-depth during their regular community meetings. A training course on animal health with focus in parasitic diseases was given on November 10th, 2012. Also, preliminary results of the llama production systems study at Marcapomacocha was delivered to the audience. Results Llamas are usually kept by individual smallholders, but a few communal enterprises have large herds in the study sites. Results presented here came from structured interviews with smallholders. The survey revealed that the main economic activity of llama farmers is livestock (alpaca, llama and sheep); the second source of income in zone 2 is the work in the nearby mines. The harsh environmental conditions do not allow any crop production (Table 2). In the majority of cases older men are family heads. Most of the interviewed farmers are married. When llama keepers are married or cohabitate it is common that men are the head of the households. The majority of farmers in the study areas have completed either primary or secondary school. Illiteracy is mainly restricted to elderly women. Table 2. Ranking of economic activities of llama farmers by zone (% of responses)* Activities Zone 1 Zone 2 Zone 3 Rank 1 Rank 2 Rank 1 Rank 2 96 20 55 42 88 12 Crops 0 0 0 0 2 9 Handicraft 0 20 0 0 0 9 Mining 0 0 11 8 2 2 Others 4 60 34 50 8 68 Livestock Rank 1 Rank 2 * Each column sum up to 100% Farmers keep different livestock species for income diversification. Therefore they keep llamas, alpacas, sheep and cattle (Table 3). On average a farmer has 35 llamas. The average number of sheep and alpacas are higher than llamas. Interviewed farmers believed that, the general trend for sheep, alpaca and llama population, in the last 5 years, is stabilizing, increasing, and diminishing respectively. 50%, 42% y 27% of respondents think that llama herds were decreasing in zone 1, 2 and 3, respectively. It seems that the majority of farmers are currently replacing llamas by alpacas. One explanation for this practice could be that alpaca fiber fetches a good price on the market. As the prices of the global fiber market are very volatile, this could be a risky enterprise. It is also interesting to note that many farmers indicated that in the coming five years they would like to increase llama herds again. The 11 results indicate that farmers try to balance the composition of their herds according to market demands. Table 3. Average herd size by zone (number of heads, means±sd) Livestock Zone 1 Zone 2 Zone 3 Llama 27±19 34±22 45±44 Alpaca 24±64 54±45 77±66 Sheep 221±131 91±61 102±75 Cattle 4±7 10±0 11±9 The main purpose of rearing llamas is for meat production. In zone 2, where mining is the main economic activity, farmers explained that llamas are mostly reared for cultural issues (Ceremony, tradition, and inheritance). Savings and the sale of hides are other reasons for llama rearing (Table 4). Table 4. Purpose for llama rearing by zone (% of responses)* Reasons Zone 1 Zone 2 Zone 3 Rank 1 Rank 2 Rank 1 Rank 2 Rank 1 Rank 2 Meat 64 44 37 55 79 14 Fiber 0 0 0 11 0 20 Cultural 9 6 58 13 6 8 Dung 0 0 0 0 0 0 Transport 0 0 3 0 5 5 Hide 0 38 2 8 0 11 Savings 27 12 0 5 3 3 Others 9 0 0 8 7 39 * Each column sums up to 100% The llama production system is a low-input and low-output system. It is based on grazing native rangelands, which belong to peasant communities. An evaluation of the rangelands showed that they are often in a very poor condition due to overgrazing, lack of fences and lack of land property. Three types of llama were reported: Kara (Light-wooled), Intermediate (Mediumwooled) and Chaku (Heavy-wooled). Llama “Kara”, which is a meat-oriented type, is the most common type in zone 1 and 3 and Llama “Intermediate” is predominant in zone 2 (Table 5). However, it is common to find the three types of llamas in a herd. Only few farmers are more interested in raising “Chakullamas”, which have more fiber. These animals are raised for animal shows, but the fiber is not sold on the market. 12 Table 5. Types of llama by zone (percentage) Type Zone 1 Zone 2 Zone 3 Kara 64 17 44 Intermediate 12 72 40 Chaku 24 11 16 * Each column sums up to 100% Figure 2. Types of llama: Kara (Light-wooled), Intermediate (Mediumwooled) and Chaku (Heavy-wooled). During the interviews farmers were asked about their current breeding practices. This information is essential as this is the starting point for the development of the breeding programs. The majority of farmers do a selection only on males, but only 44% of farmers practiced selection for both males and females. Llamas are selected by using visual appraisal, and the common selection criteria are height, conformation and color. In zone 1, farmers have preference for Guanaco type llamas. In most cases, replacement animals came from the own herd, but farmers of zone 3 are prompt to buy llamas from other regions. At the moment there are no joint activities of farmers to improve their animals, but one could observe that the breeding objective across farmers is very similar. This is a good starting point for a breeding program as there is a common interest. None of the farmers keeps written records about pedigree, production and reproduction performance. Most of the farmers (77%) explained that they had not received any type of support for improving their current management strategies. Only a few farmers got training on pasture management, meat processing (production of charqui) and handicrafts. But this training focused more on alpacas than on llamas. Support was only provided by an NGO called FODESA, which is currently active in some villages of the study region. So far farmers did not receive support from the local government. Although farmers face a number of challenges, they are still interested to continue llama rearing in the future. The majority of the interviewees even 13 indicated that they consider increasing the number of llamas in the future. Main reasons given are: llamas provide more meat than alpacas, llamas are more resistant to diseases and can better cope with harsh environment (poor pasture quality) and can provide a good and stable income. One can conclude that the production system is a low-input low-output system, where little investments are made and where farmers receive little or no support for improving management strategies. Although the current market value for llamas is not high, llamas still have their role in the production system and are seen as an alternative source of income. Outcome 2. Phenotypic characterization of three llama populations Activity 3. Phenotypic characterization A total number of 1071 llamas covering complete age range, gender, and three types of llamas (Kara, Chaku and intermediate) have been recorded (Table 6). Table 6. Number of herds and llamas recorded by zone and type Zone Herds Llamas recorded (head) Kara Chaku Intermediate Total 1 14 174 --- ---- 174 2 17 242 24 107 373 3 18 356 168 ---- 524 Total 49 772 192 107 1071 The following phenotypic data have been collected for each animal (Figure 3): Height at withers (cm) Height at poll (cm) Height at rump (cm) Length of neck (cm) Thoracic circumference (cm) Length of body (cm) Cannon bone circumference (cm) Length of ear (cm) Body weight (kg) From a sub-sample of 137 lamas Chaku, fibre samples have been taken for fibre quality analysis in the animal fibre laboratory of UNALM. Average and standard deviation of fiber diameter were measured from staple samples by microprojection method (IWTO-8-2011). The field work was carried out by the support of Masters students from UNALM and llama farmers. 14 Figure 3. Body measurements Results Phenotypic characterization work started at zone 1 in January 2012. Then the same work was done at zone 2 and zone 3 from April to June 2012. Additional measurements such as height at poll, cannon bone circumference, and length of ear were added to phenotypic characterization in these zones. It seems that llama population from the study sites differs in many aspects from other llama populations. Animals are on average taller, larger and have a higher body weight. This indicates a high potential for meat production. A high phenotypic variation in body weight and cannon bone circumference was observed, mainly due to among herd variation (Table 7 and 8). More research is needed to elucidate the source of this variation (genetic or environment), and to estimate genetic parameters such as heritability and genetic correlations among traits. Table 7. Average of body measurements for llamas Kara in Zone 1 Measurement Unit N mean±sd cv(%) Height at poll (ACa) cm 45 183.9±9.6 5.2 Height at withers (AC) cm 174 108.7±8.6 7.9 Height at rump (AG) cm 174 109.6±9.9 9.1 Length of neck (LC) cm 174 63.5±9.1 14.3 Thoracic circumference (PT) cm 174 115.1±13.6 11.8 Cannon bone circumference (PC) cm 26 13.7±3.1 22.7 Body weight (PV) kg 174 108.1±33.7 31.2 15 Table 8. Body measurements for llamas Kara and intermediates in Zone 2 and 3 Measurement Unit n mean±sd cv(%) Height at poll cm 677 162.8±15.8 9.7 Height at withers cm 677 104.2±9.5 9.1 Height at rump cm 677 105.6±9.5 9.0 Length of neck cm 677 55.8±7.4 13.2 Thoracic circumference cm 677 115.5±13.3 11.5 Length of body cm 677 122.4±13.4 10.9 Cannon bone circumference cm 677 11.6±1.7 14.9 Length of ear cm 677 16.6±2.2 13.4 Body weight kg 677 102.6±32.8 31.9 In Sacrafamilia (zone 3) it was interesting to observe that farmers kept a larger number of Chaku llamas. As expected the average of fiber diameter was finer in young llamas than in older ones (Table 9). Also, fibers from young animals are on average less or equal 22 microns which corresponds to alpaca baby class. So, Chaku fiber shows adequate fiber average diameter to be sold in the market, maybe it is sold as alpaca. However, more research is needed to study factors affecting fleece weight, shearing interval, fiber loss, and the presence of hairymedullated fibers across fleece. Table 9. Average of fiber diameter for llamas Chaku in Sacrafamilia (Zone 3) Age Sex Milk Two Four Six tooth tooth tooth tooth 22 6 11 Average (μm) 21.4 22.0 S.D. (μm) 1.81 1.4 Items Number of animals Male Female 89 32 96 23.5 27.6 24.6 26.4 1.5 3.8 3.2 4.4 During the phenotypic characterization Llamas Kara were assigned to the following categories: ABCD- Excellent conformation, kara type, good height Good conformation, kara type, good height Regular conformation, regular kara type, regular height Poor conformation, kara type not well defined, poor height 16 Llamas belongs to category A and B were tagged and selected to be used as parents in the next mating season. These activities were the first step for implementing genealogy registry in the study zones. Outcome 3. Breeding strategies and social networks Activity 4. Documentation of breeding strategies and social networks All farmers, who were interviewed also provided information on the progeny history of three selected animals. The best breeding male and the two best breeding females of each herd were identified. The origin (own herd or different source), service period and important characteristics were recorded. For each female the number of offsprings, number of abortions and fate of the offspring (sold or remained in the herd) was documented. This information can be used for the identification of current breeding practices. The preliminary results of the interviews and discussions showed that the main and almost only purpose of rearing llamas in the region is the production of meat. This is reflected in very homogenous answers related to the selection criteria. The research team therefore decided to omit the ranking exercise as no new insights were expected. The social network analysis was performed with all interview partners in order to obtain information on current breeding strategies. Results The majority of the farmers use male and female animals from their own herd for replacement. This practice can lead to an increase of inbreeding rate over a longer period. Especially replacement females are recruited from the own herd. Only about 20% of interviewees stated that they sometimes purchase new breeding males from other farmers in other regions. Alternative practices such as exchange of males or lending or renting of breeding stock are not common in the study sites. Farmers stated that they usually try to keep the offspring of their best animals. But if there is a need for immediate cash, animals are sold either as breeding stock or for meat production. Only about 41%, 34% and 56% of interviewees stated that they select both males and females in zone 1, 2, and 3 respectively. Farmers applied their own criteria to select replacements by visual appraisal, but most of them preferred taller and larger animals with good body conformation. In zone 1, farmers have more preference for “Guanaco” type llamas. Males and females, young and old llamas are maintained together during the mating season in open rangelands, so parent identification is not feasible. In addition, artificial insemination and embryo transfer are not used by farmers. In more informal interviews farmers explained that animals are frequently sold to other regions in Peru, especially to Puno in the south. It was explained that their animals are well known in different regions of the country. At the same time concerns were raised by several people that this practice might have negative consequences in the future as the region might lose the best animals in the future. 17 Outcome 4. Design and implementation of breeding strategies Activity 5. Development of improved breeding strategies Based on the findings of Activity 1 to 4 improved breeding strategies were designed. Strategies varying in complexity will be considered in accordance with institutional arrangements, opinions of the community and the baseline performance data on the breeds in question. Deterministic simulation of alternative breeding programs with ZPLAN was postpone after to get a general agreement among stakeholders about main characteristics of the breeding program. Activity 6. Implementation of new breeding strategies The community and research team took the first steps in outlining and implementing the agreed breeding plan(s) in all three locations. Llamas were selected and tagged by the project team, and records from the phenotypic characterization were saved in a digital file. Results A multi-stakeholder consultation process in each study region was the starting point for the design of community-based breeding programs (CBP). During this initial phase personal interviews with farmers, but also a series of workshops with farmers, representatives of local government, an NGO and universities were held. These platforms were used to distribute information on breeding programs, but also to discuss and agree on level of involvement, roles and responsibilities of different stakeholders in a breeding program. Repeated field visits were needed to explain the main objective of a breeding program. It was made clear that a breeding program can only be successful if there is a long-term commitment and interest from different actors. There were also discussions held to explain that breeding activities should also be accompanied by supporting actions (e.g. veterinary service, pasture improvement). Therefore the research team included also a veterinarian of UNALM to provide specific training to farmers. Finally, in Pasco, a llama breeders association was formed and is officially recognised by local institutions. This is an important step as this will give the association the negotiation power to discuss with the local government possible support actions. In Marcapomacocha the project faced a delay in getting an agreement with farmers. In this community the term of the president and his team ended and after the elections a new team is now leading the community. Therefore the project team had to re-start discussions and explanations with the new leaders. Finally, they were convinced that they would like to continue with the collaboration. Different technical details of alternative breeding strategies, such as central versus dispersed nucleus, were presented and discussed with farmers. This was an important step in the discussion as this has implications on logistics and administration of the breeding program. This participatory approach with the involvement of different actors ensures commitment and ownership of all parties 18 which is a pre-requisite for the long-term sustainability of a breeding program. Two community-based breeding programs were outlined, one in Zone 1 at Junin Region, and another in Zone 2 and 3, both located at Pasco Region. Llama farmers from Zone 2 and 3 decided to form a llama breeders association (PROLLAMA) to run together a community-based breeding program. Main features of these programs are presented in Table 10. Table 10. Main characteristics of proposed community-based breeding programs Item Breeding Program A Breeding Program B Zone 1 2 and 3 Region Junín Pasco Type of llamas Kara Kara Type of nucleus Central Dispersed nucleus Number of farmers 15-20 100-200 Size of nucleus 100 females and 15 200 females males males Multipliers None Yes Base 600 females 1000 females Organization Local committee and 30 at PROLLAMA-Llama Marcapomacocha Peasant breeders association Community Genetic evaluation Performance test Performance test Recording system Yes Yes Genealogy registry Yes Yes Identification Ear tags Ear tags Objectives Improve growth rate and Improve growth rate and conformation conformation Selection criteria Body weight Body weight Mating method Controlled Controlled Mating system Mate best to best with Mate best to best with inbreeding constraint inbreeding constraint It was not possible to start with one common breeding program for all regions, mainly due to political division and long distance between llama sites in Junin and Pasco regions. In zone 1, Marcapomacocha and Sangrar sites are part of Marcapomacocha peasant community, so decisions about the CBD are taken at 19 Community Assembly. It is reasonable to form a one central open nucleus without multiplier strata in zone 1 since a few number of farmers will be enrolled in the CBD. In contrast, farmers from zone 2 and 3 came from about 20 peasant communities of Pasco region, so decisions about the CBD will be taken by the llama breeders association. There is no general agreement to have one central nucleus, so the implementation of a dispersed open nucleus seems to be acceptable by members of PROLLAMA. At at least 3 nucleus will be implemented with possible locations at Ninacaca, San Pedro de Racco, Tactayo or Pucunan . 6 Scientific publications and publications in local media Many abstracts and oral presentations were offered in different meetings at regional and international level. Three abstracts were submitted and presented in international conferences: Gutierrez G., E. Flores, J. Ruiz, E. Schrevens, and M. Wurzinger. 2012. Alpacas and Llamas in Peru: Comparison of two production systems – How does the future look like?. In Proceedings of the 63rd Conference of EAAPEuropean Association of Animal Production. Bratislava, Slovakia. Gutiérrez G., A. Mendoza; B. Wolfinger, E. Quina, y M. Wurzinger. 2012. Crianza de llamas en la sierra central del Perú. En Resúmenes del XIII Simposio Iberoamericano sobre Conservación y Utilización de Recursos Zoogenéticos. Asunción, Paraguay. Gutiérrez, G., A. Mendoza.; B. Wolfinger, E. Quina, A. Rodríguez, M. Mendoza, F. Tantahuilca, y M. Wurzinger. 2012. Caracterización de la crianza de llamas de la sierra central del Perú. En resúmenes del VI Congreso Mundial de Camelidos Sudamericanos. Arica,Chile. One abstract was submitted and accepted by organizers of the European Association of Animal Production Annual Meeting 2013. Wurzinger M., Rodriguez A., G. Gutierrez. 2013. Design of a communitybased llama breeding program in Peru: a multi-stakeholder process. Abstract accepted at EAAP- European Association of Animal Production Annual Meeting 2013, Nantes, France. A Master thesis named “Characterisation of the production systems of llamas and description of breeding strategies of smallholders in the Central Peruvian Andes” was published at BOKU by Brigitta Wolfinger. The thesis is free-available on line. Thesis of five Peruvian master students and one doctoral student at UNALM is expected to be done in 2013. 20 7 Theses The project supports Masters students from both universities to do their research for their Master thesis. The working titles of the theses are as follows: Brigitta Wolfinger (BOKU): Characterization of the production system of llamas and description of breeding strategies of smallholders in the Central Peruvian Andes Emma Quina (UNALM): Rearing systems and phenotypic characterization of llama population in Marcapomacocha, Junin. Alexandra Cynthia Mendoza (UNALM): Production systems and breeding strategies of llama farmers in Pasco. Folke Tantahuilca (UNALM): Phenotypic characterization of llama Chaku in Sacrafamilia, Pasco. Jorge Mendoza (UNALM): Evaluation of body measurements for llama Kara selection in Pasco. Marcos Calderón (UNALM): Design of a community-based breeding program for a llama population in Marcapomacocha Another Peruvian student, Anibal Rodriguez, was supported by the project to do his field work for his PhD thesis. He is an associate professor at Daniel Alcides Carrion University in Pasco. His thesis is named “Comparison of three community-based breeding schemes for llama farmers in Pasco”. 8 Follow-up project activities The project team could jointly with a research team from Bolivia secure additional funding for 2013-2014. The FAO-funded project “Capacity strengthening for implementing breeding strategies for llamas in Bolivia and Peru” has three main activities: human capacity development, development of a data base and continue technical support of local farmers. The project offers for students, researchers, but also livestock keepers different short courses. In addition, regular field visits to the communities enable the research team to keep in contact with the farmers and further develop and implement the jointly designed breeding strategies. A database, hosted by UNALM, will be used to store and analyze field data on performance of animals. This is the base for calculation of genetic parameters and in the future also the estimation of breeding values. The breeders association of Pasco will present, supported by the project team, a concept to the local government to get financial support for further development of the llama sector. They seek the implementation of llama production system improvement program with emphasis in capacity-building, breeding, health, nutrition and market access for llama products as fresh and “Charqui” (dried and salty meat) 21 In April 2013 an additional project proposal was submitted to the PerezGuerrero-Trust. The idea of this proposal is to enable interaction between researchers in Argentina, Bolivia and Peru. A decision on funding is expected by October 2013. 22 Future activities Based on the findings of this project new research and development topics where identified: Estimation of genetic parameters and correlations of various traits Establishment of a routine for estimation of breeding values Different feeding strategies for final fattening of male llamas, which are not used in the breeding program, should be assessed. One possible option is the use of improved pasture. A more detailed and systematic analysis of the local and regional meat market. Impact assessment of breeding programs Molecular characterization of llama population Technical support of livestock keepers related to herd management, but also processing and marketing of products. 23 References Caceres C., Y. 2002. Análisis del sistema de valor del sub sector de carne de alpaca y llama. Tesis para optar el grado de Magister Scientiae en la especialidad de Agronegocios. Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina. FAO. 2005. Situacion actual de los Camelidos Sudamericanos en Peru. Gutierrez R. G. 1993. Masticación ingestiva y fragmentación de forrajes de diferente longitud en ovinos, alpacas y llamas. Tesis para optar el grado de Magister Scientiae en la especialidad de Produccion Animal. Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina. Maquera LL., E. 1991. Caracterización y persistencia fenotípica en llamas Karas y lanudas del Centro Experimental La Raya - Puno. Tesis para optar el grado de Magister Scientiae en la especialidad de Produccion Animal. Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina. Ministerio de Agricultura. 2010. Dinámica Agropecuaria 1997-2009. Oficina de Estudios Económicos y Estadísticos, Perú. Ruiz J.B.; Gutiérrez G.A. y Velarde R.F. 2004. Producción y comercialización de los productos de los pequeños rumiantes y camélidos sudamericanos en el Perú. In: “La comercialización de los productos de los pequeños rumiantes y camélidos sudamericanos”. Publicación RED CYTED XIX, México. Páginas 119-126. Siguayro P, R. 2010. Comparación de las características físicas de las fibras de la llama ch'aku (Lama glama) y la alpaca Huacaya (Lama pacos) del Centro Experimental Quimsachata del INIA - Puno. Tesis para optar el grado de Magister Scientiae en la especialidad de Produccion Animal. Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina. 24 Annex I Alpacas and Llamas in Peru: Comparison of two production systems – How does the future look like? G. Gutierrez1, E. Flores1, J. Ruiz1, E. Schrevens2, M. Wurzinger3 1 UNALM-Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Lima, Peruffd 2 KU-Leuven, Leuven, Belgium 3 BOKU-University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, Austria Alpacas and llamas are kept next to each other in the central highlands of the Peruvian Andes, where crop production is not feasible due to low temperature. The aims of two studies were to document the current situation of Alpaca and llama rearing and identify the dynamics and on-going changes of the two different systems. The studies were carried out in the Department of Cerro de Pasco where a total number of 106 llama keepers and 23 Alpaca breeders were interviewed using a semi-structured questionnaire. First results show a clear distinction of both systems. Llamas are usually kept by individual smallholders. On the contrary, Alpacas are kept by farmers´ cooperatives, where the animals remain property of the farmers, or in large community farms, where animals are owned by the community. This is also reflected in larger Alpaca herds. Llamas are traditionally kept for meat production and are used as pack animals, whereas Alpacas are kept for fibre. Farmers put more emphasis, time and money in improving the management of Alpacas. They purchase better breeding males from different sources, whereas llama males are often replaced by animals from the own herd or are obtained from neighbours. NGOs and the local government promote a more market oriented Alpaca production and support farmers in their efforts by providing training and other inputs. On the other hand, the predicted impact of climate change for this region indicates a reduction in precipitation and as a consequence reduced pasture growth. This would actually favour llamas, which are known to be better adapted to harsh and dry conditions. There seems to be a dichotomy between the economic advantage of Alpacas in the short run and the possible more ecological sustainable llama production in the future. 25 Annex II Área Temática: Sistemas ganaderos sustentables con la participación de razas locales Crianza de llamas en la sierra central del Perú Gustavo Gutierrez1*, Alexandra Mendoza1; Brigitta Wolfinger2, Emma Quina1, María Wurzinger2 1 Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Programa de Investigación en Ovinos y Camélidos Americanos, Lima. Perú.*gustavogr@lamolina.edu.pe 2 BOKU-University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Department of Sustainable Agricultural Systems, Viena, Austria Los objetivos del estudio fueron describir el sistema de crianza e identificar las estrategias locales de manejo genético de los rebaños de llamas en los distritos de Simón Bolívar y Santa Ana de Tusi (Zona 1), Huayllay (Zona 2) y Marcapomacocha (Zona 3) de la sierra central del Perú. 126 criadores de llamas fueron encuestados durante Junio del 2011 a Enero del 2012. El principal objetivo de la crianza de llamas es la producción de carne. El sistema de crianza es extensivo basado en el uso de pastizales de propiedad comunal. El rebaño promedio es mixto, compuesto por llamas, alpacas, ovinos, y vacunos. El número promedio de llamas por criador fue de 45, 34 y 27 en la zona 1, 2 y 3 respectivamente. La población de llamas ha disminuido en los últimos 5 años en 27% , 42% y 50% de los rebaños de la zona 1, 2 y 3, respectivamente, signo de erosión genética de este recurso. El 56%, 34% y 41% de los criadores realiza selección en hembras y machos en la zona 1, 2 y 3 respectivamente. El tipo de llama predominante es el tipo pelada, seguido por intermedio y lanuda. Los criterios de selección son la altura, la conformación corporal y el color. El empadre es continuo y no controlado. Las hembras y machos de reemplazo provienen mayoritariamente del propio rebaño, seguido de compras e intercambio. Los criadores perciben la necesidad de mejorar sus pastos, la genética de sus rebaños y su accesibilidad al mercado. Se sugiere la elaboración de una estrategia participativa de mejoramiento del sistema de producción. Palabras claves: Llama, pelada, Perú. 26 Annex III. CARACTERIZACIÓN DE LA CRIANZA DE LLAMAS DE LA SIERRA CENTRAL DEL PERÚ Gutierrez1*, G., Mendoza1 A.; Wolfinger2 B., Quina1 E., Rodriguez1 A., Mendoza1 M., Tantahuilca1 F., Wurzinger2 M. 1 Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Programa de Investigación en Ovinos y Camélidos Americanos, Lima. Perú.*gustavogr@lamolina.edu.pe 2 BOKU-University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Department of Sustainable Agricultural Systems, Viena, Austria INTRODUCCIÓN: La llama (Lama glama) es una especie nativa de los altos andes, cuya crianza esta asociado a pequeños criadores. Existe una población única de llamas en la sierra centra del Perú (Gutiérrez y col., 2012), que no tiene una caracterización completa. Los objetivos del estudio fueron: a) describir el sistema de crianza, b) identificar las estrategias locales de manejo genético de los rebaños de llamas, y c) caracterizar fenotípicamente las llamas de la Sierra Central del Perú. MATERIALES Y MÉTODOS: La zona de estudio comprendió los distritos de Simón Bolívar y Santa Ana de Tusi (Zona 1), Huayllay (Zona 2) y Marcapomacocha (Zona 3) de la sierra central del Perú. 126 criadores de llamas fueron encuestados y 1071 llamas fueron medidas para peso vivo, altura a la cabeza, cruz, y grupa, circunferencia de tórax, cuello y caña anterior, largo de cuerpo, cuello y de grupa, durante Junio del 2011 a Julio del 2012. RESULTADOS: El principal objetivo de la crianza de llamas es la producción de carne. El sistema de crianza es extensivo basado en el uso de pastizales de propiedad comunal. El rebaño promedio es mixto, compuesto por llamas, alpacas, ovinos, y vacunos. El número promedio de llamas por criador fue de 45, 34 y 27 en la zona 1, 2 y 3 respectivamente. Los criadores que han percibido que la población de llamas ha disminuido en los últimos 5 años son 27%, 42% y 50% de los encuestados de la zona 1, 2 y 3, respectivamente. El 56%, 34% y 41% de los criadores realiza selección en hembras y machos en la zona 1, 2 y 3 respectivamente. El tipo de llama predominante es el tipo pelada, seguido por intermedio y lanuda. Los criterios de selección son la altura, la conformación corporal y el color. El empadre es continuo y no controlado. Las hembras y machos de reemplazo provienen mayoritariamente del propio rebaño, seguido de compras e intercambio. La variabilidad fenotípica fue alta para las características biométricas evaluadas debido al efecto de la edad, sexo, rebaño y zonas de estudio. CONCLUSIONES: El sistema de crianza corresponde a un sistema de producción mixto y de bajos insumos. Los criadores perciben la necesidad de mejorar sus pastos, la genética de sus rebaños y su accesibilidad al mercado. Se sugiere la elaboración de una estrategia participativa de mejoramiento del sistema de producción. REFERENCIAS: Gutierrez G., E. Flores, J. Ruiz, E. Schrevens, and M. Wurzinger. 2012. Alpacas and Llamas in Peru: Comparison of two production systems – How does the future look like?. In Proceedings of the 63rd Conference of EAAP-European Association of Animal Production. Bratislava, Slovakia. Palabras claves: Llama, caracterización, Perú. 27 Annex IV. CARACTERIZACIÓN DE LA CRIANZA DE LLAMAS DE LA SIERRA CENTRAL DEL PERÚ Gutierrez1*, G., Mendoza1 A.; Wolfinger2 B., Quina1 E., Rodriguez1 A., Mendoza1 M., Tantahuilca1 F., Wurzinger2 M. 1 Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Programa de Investigación en Ovinos y Camélidos Americanos, Lima. Perú.*gustavogr@lamolina.edu.pe 2 BOKU-University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Department of Sustainable Agricultural Systems, Viena, Austria INTRODUCCIÓN: La llama (Lama glama) es una especie nativa de los altos andes, cuya crianza esta asociado a pequeños criadores. Existe una población única de llamas en la sierra centra del Perú (Gutiérrez y col., 2012), que no tiene una caracterización completa. Los objetivos del estudio fueron: a) describir el sistema de crianza, b) identificar las estrategias locales de manejo genético de los rebaños de llamas, y c) caracterizar fenotípicamente las llamas de la Sierra Central del Perú. MATERIALES Y MÉTODOS: La zona de estudio comprendió los distritos de Simón Bolívar y Santa Ana de Tusi (Zona 1), Huayllay (Zona 2) y Marcapomacocha (Zona 3) de la sierra central del Perú. 126 criadores de llamas fueron encuestados y 1071 llamas fueron medidas para peso vivo, altura a la cabeza, cruz, y grupa, circunferencia de tórax, cuello y caña anterior, largo de cuerpo, cuello y de grupa, durante Junio del 2011 a Julio del 2012. RESULTADOS: El principal objetivo de la crianza de llamas es la producción de carne. El sistema de crianza es extensivo basado en el uso de pastizales de propiedad comunal. El rebaño promedio es mixto, compuesto por llamas, alpacas, ovinos, y vacunos. El número promedio de llamas por criador fue de 45, 34 y 27 en la zona 1, 2 y 3 respectivamente. Los criadores que han percibido que la población de llamas ha disminuido en los últimos 5 años son 27%, 42% y 50% de los encuestados de la zona 1, 2 y 3, respectivamente. El 56%, 34% y 41% de los criadores realiza selección en hembras y machos en la zona 1, 2 y 3 respectivamente. El tipo de llama predominante es el tipo pelada, seguido por intermedio y lanuda. Los criterios de selección son la altura, la conformación corporal y el color. El empadre es continuo y no controlado. Las hembras y machos de reemplazo provienen mayoritariamente del propio rebaño, seguido de compras e intercambio. La variabilidad fenotípica fue alta para las características biométricas evaluadas debido al efecto de la edad, sexo, rebaño y zonas de estudio. CONCLUSIONES: El sistema de crianza corresponde a un sistema de producción mixto y de bajos insumos. Los criadores perciben la necesidad de mejorar sus pastos, la genética de sus rebaños y su accesibilidad al mercado. Se sugiere la elaboración de una estrategia participativa de mejoramiento del sistema de producción. REFERENCIAS: Gutierrez G., E. Flores, J. Ruiz, E. Schrevens, and M. Wurzinger. 2012. Alpacas and Llamas in Peru: Comparison of two production systems – How does the future look like?. In Proceedings of the 63rd Conference of EAAP-European Association of Animal Production. Bratislava, Slovakia. Palabras claves: Llama, caracterización, Perú. 28 Annex V. Design of a community-based llama breeding program in Peru: a multistakeholder process M. Wurzinger1, A. Rodriguez,2,3 G. Gutierrez2 1 BOKU-University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, Austria 2 UNALM-Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Lima, Peru 3 Universidad Nacional Daniel Alcides Carrion, Cerro de Pasco, Peru The Peruvian llama population counts about 1 million animals and the sale of meat and breeding animals is of economic importance for many smallholders. Nevertheless, there are a number of factors hindering a higher productivity, one of them are well established breeding programs. The llamas of the central highlands (Department of Junin and Pasco) are well-known by llama producers as they these animals are very tall and heavy and breeding stock is sold every year to other regions of Peru. Farmers raised their concern of losing potentially good genetics, when there is no concerted breeding management in place. Therefore the aim of this study was the design of a community-based breeding program and a multi-stakeholder consultation process was started. This involved personal interviews with farmers, but also a series of workshops with farmers, representatives of local government, an NGO and universities. These platforms were used to distribute information on breeding programs, but also to discuss and agree on level of involvement, roles and responsibilities of different stakeholders in a breeding program. In a first step, 70 farmers of 20 communities agreed to form a breeders association. At the same time a phenotypic characterization of the llama population was performed. In addition, a preliminary market analysis was carried out to get a better understanding of the complete value chain of llama meat. Alternative breeding strategies, such as central versus dispersed nucleus, were presented and discussed with farmers. This participatory approach with the involvement of different actors ensures commitment and ownership of all parties which is a pre-requisite for the longterm sustainability of a breeding program. 29