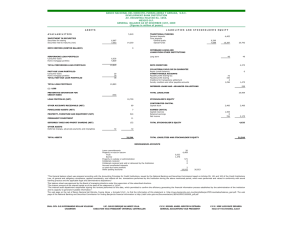

Essentia White Papers Delivering Behavioral Alpha® The Alpha Lifecycle New research into the nature of investment alpha and what portfolio managers can do to sustain it. Chris Woodcock Alesi Rowland Snežana Pejić, Ph.D. ESSENTIA WHITE PAPERS Research Authors Chris Woodcock Head of Product and Research chris.woodcock@essentia-analytics.com Alesi Rowland Research Analyst alesi.rowland@essentia-analytics.com Snežana Pejić, Ph.D. VP Data Science snezana.pejic@essentia-analytics.com About Essentia Essentia Analytics is a leading provider of behavioral data analytics and consulting for professional investors. Led by a team of experts in investment management, technology and behavioral science, Essentia combines nextgeneration data analytics technology with human coaching to help active fund managers capture performance that was previously being lost to biases or other common decision-making deficiencies. Contact us to find out more: info@essentia-analytics.com www.essentia-analytics.com Page 1 | The Alpha Lifecycle The Alpha Lifecycle Summary of Findings • Our in-depth analysis of 43 portfolios over 14 years demonstrates that alpha has a distinct and persistent lifecycle. It tends to accumulate in the early phase of an investment and decay over time — often precipitously. • On average, positions are held too long, leading to a 7 basis point peak-toexit negative portfolio impact per position. • We have identified four main alpha lifecycle trajectories; the majority show value-add early on, but conclude with an overall negative return on investment. • The trajectories identified were assessed statistically through mixed effect modelling. Wald’s tests of the models employed indicated that they significantly accounted for variance within our dataset. • We assert that these findings are a manifestation of the endowment effect, a well established behavioral bias where agents tend to ascribe greater value to an object for which they perceive ownership. © Essentia Analytics Ltd. All rights reserved. The Alpha Lifecyle | Page 2 ESSENTIA WHITE PAPERS Foreword Breaking up is hard to do, as the old song says. It’s increasingly welldocumented that, in practice, active fund managers are better buyers than sellers. But what does that actually mean? How is it manifest, and what, if anything, can be done about it? In this paper, we examine whether, and to what effect, managers tend to hang on to positions past their sell-by dates. Are their individual ideas generating alpha — and if so, for how long? The result is very powerful: on average, we see active equity fund managers do generate alpha — a meaningful amount, in fact. But the majority of them tend to ultimately give all of that alpha back (and then some) by holding on too long. We work with many long-term investors, and having been fundamental stockpickers ourselves, we have strong respect for the long-term approach. But it is possible — easy, in fact — to overstay our welcome in a given stock, and human biases often lead us to do just that. This research shines a light into a very important topic that has so far received only limited, mostly anecdotal, exposure. We have mapped the alpha lifecycle for a large cohort of real-world investors, and quantified both its accumulation and (in most cases) its eventual decay. That’s useful to us, at Essentia, in helping our clients understand their own alpha lifecycles and optimize their investment processes accordingly. But we share this work with broader goals in mind: to advance the industry’s understanding of the nature of alpha generation, and contribute new evidentiary perspective to the discussion about the value of active portfolio management. Clare Flynn Levy CEO, Essentia Analytics Page 3 | The Alpha Lifecycle Introduction Alpha — the measure of a portfolio manager’s ability to add value beyond the effect of the overall market — remains the preeminent performance metric when attempting to measure skill. In an environment where low-cost index funds are perceived by many to offer better overall returns than their activelymanaged counterparts, the ability to assess a given manager’s alpha — and for active managers to contribute maximum alpha to their portfolios — is more critical than ever. To do that, we must first understand alpha’s characteristics and effects. With that in mind, we set out to validate and better understand an aspect of alpha that has long been assumed but never demonstrated: that it has a life cycle — a beginning, middle and end — and that investors often hold on to positions too long, potentially diminishing whatever excess returns they were able to generate early on. Our analysis examined roughly 10,000 “episodes” — full cycles of a given position from first entry to last exit — across 43 portfolios over 14 years. The results demonstrated what we (and many other researchers) suspected: there’s a clear lifecycle to alpha that, in general, starts strong and fades with age. What surprised us is the magnitude of this effect: the average episode’s alpha trajectory followed an inverted horseshoe pattern — and finished with a loss of over 2%! The Alpha Lifecycle: Most of the time, managers add value early in the period they hold a position, only to lose it precipitously at the end Our methodology for this research is described in detail below. While our research was focused on validating and quantifying the alpha lifecycle itself, we also present some thoughts on why alpha tends to behave as it does — we believe it is a classic example of the endowment effect, one of the most common investor behavioral biases, at work. The Alpha Lifecyle | Page 4 ESSENTIA WHITE PAPERS Finally, while the alpha lifecycle diagram isn’t pretty, the good news is there’s generally a significant period of outperformance before the tide shifts — demonstrating the value that active managers can add above indexed portfolios. Managers can — and do — add meaningful sustained alpha when they exercise discipline in their exit timing, and avoid the biases that can lead to holding on too long; we offer some thoughts on how in our conclusion below. Methodology and assumptions Sampling/Trimming A total of 43 equity portfolios from clients of Essentia Analytics were analyzed for this study. The total number of episodes — each of which represents a single investment from the opening to the final trade — in this dataset, over all portfolios, was 14,058. All episodes that remained open at the close of the sample period were omitted. Also, any episodes that were under 20 business days long were removed, leaving a final sample of 9,254 episodes of varying lengths (μ = 257, σ = 319, MAX = 2,638). The mean number of episodes per portfolio was 215 with a standard deviation of 207. The smallest number of episodes in a given portfolio was 23 and the largest was 1,208. Before conducting the main analyses, we investigated the nature of the episodes within our data set. Specifically, we identified the start year and length of each episode (Figures 1 & 2). Figure 1. Bar plot showing the number of episodes opened in each year. The value above each bar represents the percentage of the total number of episodes starting in that year. Page 5 | The Alpha Lifecycle Figure 2. Bar plot showing the frequency of different episode lengths within the data set. The value above each bar denotes the percentage of the data set within that episode length bound. From these plots, it is clear that the majority of episodes within this data set began between 2012 and 2018 (92.84%). Over all the data, the majority of episodes were under 500 business days long (85.54%). Therefore, our analysis is most pertinent to episodes with these qualities. Preprocessing/interpolation For each episode in each portfolio, cumulative relative impact (RI) and cumulative return on investment (ROI) were computed. RI is defined as the relative profit of that episode on that day divided by the absolute amount invested in the portfolio on that day (relative profit is the total increase in value in the investment on that day, minus a hypothetical investment in the benchmark of the same amount). Similarly, ROI was defined as the relative profit on that day over the absolute total capital invested in that stock on that day. As illustrated above, the episodes in this dataset vary considerably in length. Although they may exhibit similar life cycles, the cycles may occur over variable time periods. Therefore, to make the episodes comparable for analysis, they were normalised temporally. Each episode other than the largest episode in the data set was interpolated so that it now possessed the same number of data points as the largest episode. Time was then converted into percentage of the episode completed. The Alpha Lifecyle | Page 6 ESSENTIA WHITE PAPERS Analysis and Observations Our main analyses were computed using the mean of each of our measures at each episode percentage for each portfolio. This enabled us to easily inspect what trends were most applicable to each portfolio manager’s data as a whole. Before modelling the dataset, a graphical inspection of each portfolio’s measures and the grand mean across all portfolios was assessed to guide which functions to fit the data to (Figure 3). Figure 3. Grand mean of cumulative ROI over all episodes. Inspection of cumulative ROI revealed that alpha accumulation may follow one of several trends. When inspecting the grand average, the data followed a concave polynomial, “inverted horseshoe” shape. At the portfolio level, the data often followed this shape or a partial version of this shape. The exception to this rule was when the data followed a positive linear gradient. Overall, we found 4 subtypes of the lifecycle of an episode (figures 4-7). We have coined each subtype, respectively, The Round Tripper, The Linear Accumulator, The Hopeless Romantic and The Coaster. Page 7 | The Alpha Lifecycle Figure 4. Mean cumulative ROI of a portfolio demonstrating “The Round Tripper” trend. The trend follows a similar trend as the grand mean plot of the same measure: a concave polynomial that demonstrates a progressive rise and then fall in alpha. Figure 5. Mean cumulative ROI of a portfolio demonstrating “The Linear Accumulator” trend. This is characterised by a positive linear gradient. The Alpha Lifecyle | Page 8 ESSENTIA WHITE PAPERS Figure 6. Mean cumulative ROI of a portfolio demonstrating “The Hopeless Romantic” trend. This is characterized by an initial short lived increase in cumulative ROI followed by a progressive decline for the remainder of the episode. Figure 7. Mean cumulative ROI of a portfolio demonstrating “The Coaster” trend. This is characterised by an initial rise in cumulative ROI which leads to a period of neither gain nor loss. Page 9 | The Alpha Lifecycle Because of these trends, we decided to fit a quadratic function to cumulative ROI. Similarly, cumulative RI’s grand mean plot (figure 8) best fit a concave polynomial and so we chose to fit a similar function to this measure. Both models were fitted using maximum likelihood estimation. Figure 8. Graph showing the grand mean cumulative RI over all episodes relative to the percentage through episode. Again, this demonstrates a progressive rise in cumulative RI followed by a steep decline prior to exit. The mean overall impact of each full episode was marginally negative; the drop from the peak to exit was drastic — 7.22 bps of RI. Each of these measures was entered into its own respective random slope mixed effect model. Both measures were predicted by the fixed effects of episode percentage and episode percentage squared, with a random effect of portfolio. Formally, the functions of these models followed the formula: y = ax 2 + bx + c + ε Where y represents the measure to be predicted, x represents episode percentage and ε represents the amount of error within the model. Both models allowed the coefficients b and c to vary by portfolio. By doing this, we allowed for the model to capture all the subtype trends other than The Linear Accumulator. The Alpha Lifecyle | Page 10 ESSENTIA WHITE PAPERS Validation Both ROI and RI models were able to account for a large amount of the variance within the data (figure 9). To assess the significance of these findings, p values for the fixed effect of percentage through episode were computed using Wald’s tests. Figure 9. Shows the results of each mixed effect model. p values refer to the significance of incorporating percentage through episode within the model. Predicted Variable p value Marginal R 2 Conditional R 2 Quadratic Term Linear Term Cumulative ROI 0.06 0.94 <0.001 <0.001 Cumulative RI 0.02 0.73 <0.001 <0.001 The models fitted to cumulative ROI and cumulative RI possessed a coefficients of -8.89 and -0.26 respectively, indicating the model found that concave, rather than convex, polynomials fit the data set better as a whole. The results of our initial analyses were highly significant, suggesting that each model could account for variance in each measure. Although the variance accounted for by the fixed effects could be considered low, there are several reasons this may be the case. Firstly, behavioral data intrinsically tends to have a lower variance accounted for by fixed effects. This is compounded by the sheer variability within the stock market. Secondly, this analysis entered all suitable data into the analysis, despite some portfolios likely better reflecting alternative functions than the one chosen here. Finally, a quadratic function assumes symmetry around its maximum, something which is unlikely in this dataset. Discussion Understanding the causes of trends in alpha is highly valuable. This is highlighted by an attempt to utilize alpha predictors to create profit maximizing algorithms (Passerini & Vazquez, 2015). Recently, a major focus of finance research has been the study of behavioral biases and subsequent irrational decision making, which in turn impact alpha. Thaler (1999) predicted that in the future, behavioral factors will be incorporated into economists’ models by default. In fact, the CAPM model has already been improved using behavioral factors (Rocciolo, Gheno & Brooks, 2018). These findings suggest that behavioral biases are highly relevant when trying to understand what drives trends in alpha. The endowment effect (Thaler, 1980) is a prominent behavioral bias which could be at play in the alpha lifecycle characteristics we observed. This is defined as a tendency to place greater value on something for which ownership is perceived. The bias is often considered a manifestation of loss aversion (Morewedge & Giblin, 2015), a component predicted by prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). The effect has been observed among investors in experimental Page 11 | The Alpha Lifecycle settings (Kalunda & Mbaluka, 2012) and by retroactively analysing the Australian stock exchange (Furche & Johnstone, 2006). Query theory (Johnson, Häubl & Keinan, 2007) aims to explain the effect, proposing that sellers will place greater focus and value on positive, rather than negative, attributes of a good. When investigating this, those considering to sell a pen reported more positive evaluations of the good than buyers (Nayakankuppam & Mishra, 2005). Therefore, the effect may be partially driven by an increased saliency of positive attributions. The prominent trends in cumulative ROI observed here can be explained in the context of these theories. That is, as an investor holds an appreciating stock, they imbue that stock with positive attributes. Once the stock appreciation begins to deteriorate or plateau and the investor is considering a sell, they give higher value to their longstanding, positive views of the stock, leading them to hold the security while clearly losing alpha. This account has similarities with the informal notion of stock-love, which refers to investors holding losing stocks that have been profitable in the past. Importantly, three of the four subtypes identified in our analysis exhibited a period of appreciation followed by either a period of depreciation or no further appreciation in which the security is held rather than sold, mimicking this narrative. This supports the notion that the endowment effect may be a causal factor of these trends. Finally, we can’t help but state the elephant-in-the-room takeaway of this research for investment managers: the alpha drop from peak to exit within each episode is dramatic — and it’s well worth the effort to try to avoid it. 7.22 bps of portfolio impact per episode is a significant opportunity cost to carry on a portfolio; managers who are able to close episodes at — or closer to — the top of their alpha curve can significantly reduce this overhead and improve performance. Conclusion We investigated the hypothesis that alpha accumulation within episodes has a life cycle which would be observable at a portfolio level. This was assessed under the assumption that different investors may exhibit different behavioral biases and strategies, causing variation in this lifecycle. Our findings support these views. Grand mean plots of both cumulative ROI and cumulative RI suggested a predominant trend of an inverted horseshoe shape over time. At the portfolio level, the cumulative ROI plots suggested the presence of four alpha life cycle subtypes. Two of these subtypes, “The Hopeless Romantic” and “The Coaster”, resemble partial versions of “The Round Tripper” and could reflect variation in investors’ entry and exit styles. Further investigation is warranted to try and gain a deeper understanding of these subtypes. Our analysis leads us to believe that these trends are manifestations of the The Alpha Lifecyle | Page 12 ESSENTIA WHITE PAPERS endowment effect. Investors frequently ascribe extra value to stocks they own simply because they own them — and thus, hold on to them longer than they should. Whatever the cause, investors should be aware of the vast amounts of alpha that are being lost to poor exit timing — and take steps to identify and reconsider positions that are past their prime in terms of alpha accumulation. The presence of “The Linear Accumulator” subtype demonstrates that it is possible to escape the steep drop in alpha that defines the latter stage of most portfolio episodes. With our work in plotting alpha and demonstrating its tendency to decay over time, we are hopeful that more investors will be mindful of their own alpha lifecycle, exit positions closer to the peak of their alpha curve rather than the trough, and capture the value-added returns that are too commonly lost to the effects of biases and poor decision-making processes. References Johnson, E. J., Häubl, G., & Keinan, A. (2007). Aspects of endowment: a query theory of value construction. Journal of experimental psychology: Learning, memory, and cognition, 33(3), 461. Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (2013). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. In Handbook of the fundamentals of financial decision making: Part I (pp. 99-127). Kalunda, E., & Mbaluka, P. (2012). Test of Endowment and Disposition Effects under Prospect Theory on Decision-Making Process of Individual Investors at the Nairobi Securities Exchange. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 3(6). 157, 171. Morewedge, C. K., & Giblin, C. E. (2015). Explanations of the endowment effect: an integrative review. Trends in cognitive sciences, 19(6), 339-348. Nayakankuppam, D., & Mishra, H. (2005). The endowment effect: Rose-tinted and dark-tinted glasses. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(3), 390-395. Passerini, F., & Vazquez, S. E. (2015). Optimal trading with alpha predictors. arXiv preprint arXiv:1501.03756. Shefrin, H., & Statman, M. (1985). The disposition to sell winners too early and ride losers too long: Theory and evidence. The Journal of Finance, 40(3), 777-790. Thaler, R. (1980). Toward a positive theory of consumer choice. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 1(1), 39-60. Thaler, R. H. (1999). The end of behavioral finance. Financial Analysts Journal, 55(6), 12-17. Rocciolo, F., Gheno, A., & Brooks, C. (2018). Explaining Abnormal Returns in Stock Markets: An Alpha-Neutral Version of the CAPM. Wason, P. C. (1960). On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task. Quarterly journal of experimental psychology, 12(3), 129-140. Page 13 | The Alpha Lifecycle DELIVERING BEHAVIORAL ALPHA Essentia Analytics is an award-winning financial technology company that provides behavioral analytics services to professional investors. Our proprietary research directly fuels our work with clients, delivering critical insights that can guide them toward their best practices, helping them turn good intentions into good habits. Essentia Nudges — personalized, automated notifications designed to mitigate behavioral bias and encourage better decision-making on an ex-ante, day-to-day basis — are a case in point. Our work in understanding the alpha lifecycle has enabled us to plot the alpha decay pattern for each client portfolio, and create the Alpha Decay Nudge, which alerts clients to individual investments that appear to be at or near their peak alpha. Learn how Essentia can help unlock the behavioral alpha — the excess return that results from mitigating one’s biases — that is hidden in your investment decision-making process. WWW.ESSENTIA-ANALYTICS.COM INFO@ESSENTIA-ANALYTICS.COM The Alpha Lifecyle | Page 14 Know thyself. Socrates © 2019 Essentia Analytics