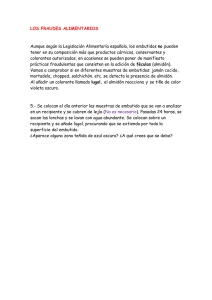

CARACTERÍSTICAS DEL ALMIDÓN DE MAÍZ Y RELACIÓN CON LAS ENZIMAS DE SU BIOSÍNTESIS CHARACTERISTICS OF MAIZE STARCH AND RELATIONSHIP WITH ITS BIOSYNTHESIS ENZYMES Edith Agama-Acevedo*, Erika Juárez-García, Silvia Evangelista-Lozano, Olga L. Rosales-Reynoso, Luis A. Bello-Pérez Centro de Desarrollo de Productos Bióticos del IPN. Km 8.5 carr. Yautepec-Jojutla, Colonia San Isidro, Apartado Postal 24, 62731. Yautepec, Morelos, México. (eagama@ipn.mx). Resumen Abstract Las tortillas de maíz azul difieren en sabor y textura de las de maíz blanco. Estas diferencias podrían atribuirse a la dureza del grano o a la estructura del almidón, la cual está influenciada por los mecanismos de su biosíntesis y repercute en la estructura de sus dos componentes principales. El objetivo del presente estudio fue analizar el almidón de maíz azul y blanco en dos etapas de desarrollo del grano, para asociar sus características morfológicas y fisicoquímicas con la estructura, y esta última con las enzimas que participan en su biosíntesis. El maíz se cosechó a los 20 y 50 d después de la polinización (ddp) y el almidón se cuantificó, y se aisló para ser caracterizado. Se extrajeron y separaron por peso molecular las enzimas de biosíntesis del almidón. El análisis de varianza fue de una vía con un nivel de significancia de p0.05. El maíz azul presentó mayor contenido de almidón. En el estudio electroforético, los dos maíces presentaron bandas con peso molecular reportado para ADP glucosa pirofosforilasa, almidón sintasa unida al gránulo y tres isoformas de almidón sintasa soluble. Además, se encontraron dos isoformas de la enzima ramificante del almidón en el maíz azul, que podrían alterar el patrón de ramificación de su amilopectina, produciendo estructuras altamente ramificadas con cadenas cortas, por lo que la estructura del almidón a los 50 ddp presentó menor espacio disponible dentro de la estructura granular para la síntesis de amilosa, así como cristales pequeños y menos perfectos que se desorganizaron a menor temperatura y entalpía que los del almidón de maíz blanco. La biosíntesis del almidón de maíz blanco y azul difirió, ya que las isoformas de la enzimas ramificante en cada uno de los maíces produjeron estructuras diferentes, lo cual repercutió en sus propiedades fisicoquímicas. Blue maize tortillas differ in taste and texture from white maize. These differences may be due to grain hardness or the starch structure, which is influenced by its mechanisms of biosynthesis and affects the structure of its two main components. The aim of this study was to analyze the blue and white maize starch in two development stages of the grain, to associate its morphological and physicochemical characteristics with the structure, and the latter with the enzymes involved in its biosynthesis. We harvested maize 20 and 50 d after pollination (DAP); and quantified starch content in the kernel, isolated and characterized it. We extracted and separated the starch biosynthesis enzymes according to their molecular weight, and used a one-way analysis of variance at a significance level of p0.05. Blue maize had higher starch content. In the electrophoretic analysis, the two maize varieties had bands of molecular weight reported for ADP glucose pyrophosphorylase granule bound synthase starch and three isoforms of soluble synthase starch. Furthermore, we found two isoforms of the starch branching enzyme in blue maize, which could alter the pattern of branching of amylopectin, producing highly branched structures with shorter chains, so that the structure of starch at 50 DAP had less available space within the grain structure for the synthesis of amylose and small and less perfect crystals, which were disorganized at lower temperature and enthalpy than those of the white maize starch. The white and blue maize starch biosynthesis differed as isoforms of branching enzymes in each maize produced different structures, which affected their physicochemical properties. *Autor responsable v Author for correspondence. Recibido: abril, 2012. Aprobado: noviembre, 2012. Publicado como ARTÍCULO en Agrociencia 47: 1-12. 2013. Key words: amylose, amylopectin, starch biosynthesis, blue and white maize. 1 AGROCIENCIA, 1 de enero - 15 de febrero, 2013 Palabras clave: amilosa, amilopectina, biosíntesis del almidón, maíz azul y blanco. Introducción E l almidón es el principal constituyente del maíz (Zea mays L.) y las propiedades fisicoquímicas y funcionales de este polisacárido están estrechamente relacionadas con su estructura. El almidón está formado por dos polímeros de glucosa: amilosa y amilopectina. Estas moléculas se organizan en anillos concéntricos para originar la estructura granular. La distribución de la amilosa dentro de los anillos concéntricos difiere entre el centro y la periferia del gránulo, ya que sólo ocupa los lugares disponibles que deja la amilopectina después de sintetizarse (Tetlow et al., 2004). La biosíntesis de la amilopectina involucra la participación de las enzimas almidón sintasa solubles (SSS, por sus siglas en inglés), que unen moléculas de glucosa mediante enlaces 1-4, produciendo cadenas lineales con diferente grado de polimerización (GP). Las enzimas ramificantes del almidón (SBE, por sus siglas en inglés), unen cadenas de glucanos mediante enlaces 1-6, originando una molécula ramificada. Una vez formada la amilopectina, la almidón sintasa unida al gránulo (GBSS, por su siglas en inglés, granule bound synthase starch) comienza a unir glucosas para sintetizar únicamente las cadenas de amilosa (Baldwin, 2001). Cada una de estas enzimas presenta isoformas (GBSS I y II; SSS I, II, III y IV; SBE I y II, que a su vez pueden ser del tipo “a” o “b”), las cuales difieren en el mecanismo de acción durante la síntesis del almidón, generando estructuras que difieren en el GP de las cadenas lineales, en la densidad y en la longitud de las ramificaciones; estas isoformas pueden o no, estar asociadas al gránulo del almidón. Para almidón de maíz blanco (silvestre, mutantes y modificados genéticamente) se conoce la función de cada una de estas enzimas e isoformas en la síntesis de la estructura en etapas tempranas del desarrollo del grano y su relación con la estructura del almidón en su etapa de madurez (Smith, 2001; Tetlow et al., 2004; Grimaud et al., 2008). Hay diferencias entre las características químicas, morfológicas, fisicoquímicas y de digestibilidad del almidón de maíz azul y blanco (Hernández-Uribe et al., 2007; Agama-Acevedo et al., 2008; Utrilla- 2 VOLUMEN 47, NÚMERO 1 Introduction S tarch is the main constituent of maize (Zea mays L.) and the physicochemical and functional properties of this polysaccharide are closely related to its structure. Starch consists of two glucose polymers: amylose and amylopectin. These molecules are arranged in concentric rings to produce the granular structure. The distribution of amylose within the concentric rings of the granules differs between the center and periphery as it only occupies the available space left by amylopectin after being synthesized (Tetlow et al., 2004). Amylopectin biosynthesis involves the participation of soluble synthase starch enzymes, which bind glucose molecules through links a 1-4, producing linear chains with different degree of polymerization (DP). Starch branching enzymes (SBE) bind chains of glucans through links a 1-6, resulting in a branched molecule. Once amylopectin is formed, the granule bound synthase starch (GBSS) begins to bind glucose to synthesize only amylose chains (Baldwin, 2001). Each of these enzymes has isoforms (GBSS I and II, SSS I, II, III and IV; SBE I and II, which in turn may be type “a” or “b”). They differ in the mechanism of action during starch synthesis, generating structures which differ in linear chains DP, in the density and length of branches; these isoforms may be associated or not with the starch granule. For white maize starch (wild, mutant and GM) each of these enzymes and isoforms has a function in the synthesis of the structure at early stages of the grain development, being related to the structure of the starch at ripening (Smith, 2001; Tetlow et al., 2004; Grimaud et al., 2008). There are differences between the chemical, morphological, physicochemical and digestibilityrelated characteristics of blue and white maize starch (Hernández-Uribe et al., 2007; Agama-Acevedo et al., 2008; Utrilla-Coello et al., 2009). In this regard, Utrilla-Coello et al. (2009) separated the starch biosynthetic enzymes using two-dimensional electrophoresis and analyzed them with MALDITOF; samples showed seven spots at 60 kDa MW with pI between 5 and 6 and were identified as GBSS1. The study was conducted on mature grains (50 d after pollination, dap), when most enzymes synthesizing starch have disappeared, except GBSS CARACTERÍSTICAS DEL ALMIDÓN DE MAÍZ Y RELACIÓN CON LAS ENZIMAS DE SU BIOSÍNTESIS Coello et al., 2009). Al respecto, Utrilla-Coello et al. (2009) separaron las enzimas biosintéticas del almidón con electroforesis bidimensional y las analizaron con MALDI-TOF; las muestras presentaron siete manchas a PM de 60 kDa con pI entre 5-6, y se identificaron como GBSS1. Dicho estudio se realizó en granos maduros (50 d después de la polinización, ddp), cuando la mayoría de las enzimas que sintetizan el almidón han desaparecido, a excepción de la GBSS (Prioul et al., 2008). El objetivo del presente estudio fue analizar el almidón de maíz azul y blanco en dos etapas de desarrollo del grano después de la polinización, para asociar sus características morfológicas y fisicoquímicas con la estructura, y esta última con las enzimas que participan en su biosíntesis. Materiales y Métodos Material biológico Se usaron variedades de maíz azul y blanco sembradas en el campo experimental del Centro de Desarrollo de Productos Bióticos (CEPROBI), ubicado en Yautepec, Morelos, México, y se cosecharon a los 20 y 50 ddp. El grano azul es un grano suave y el blanco es duro. Del maíz se retiró manualmente el pericarpio, el pedicelo y el germen, para obtener el endospermo, parte de este fue molido y la pasta resultante se pesó en porciones de 2 g, se congeló con nitrógeno líquido y almacenó a 20 °C para realizar el análisis electroforético de las proteínas. El resto de endospermo se secó 24 h a 40 °C en una estufa de convección (Riossa, modelo HS, México). El polvo obtenido se usó para aislar el almidón y realizar su caracterización. Contenido y aislamiento del almidón en el endospermo El contenido de almidón se cuantificó mediante la técnica de Goñi et al. (1997). Se aisló el almidón del endospermo con la metodología propuesta por Utrilla-Coello et al. (2009). Amilosa aparente y distribución de tamaño de los gránulos de almidón Se cuantificó por el método de Hoover y Ratnayake (2002). La distribución de tamaño de los gránulos del almidón fue determinado por análisis de difracción de rayo láser (Malvern Instruments, modelo 2000, USA). (Prioul et al., 2008). The aim of this study was to analyze the blue and white maize starch in two stages of development of the grain after pollination, to associate its morphological and physicochemical properties with the structure, and the latter with the enzymes involved in its biosynthesis. Materials and Methods Biological material We used blue and white maize varieties, planted in the experimental field of Centro de Desarrollo de Productos Bióticos (CEPROBI) (Biotic Product Development Center), located in Yautepec, Morelos, Mexico, and harvested at 20 and 50 dap. The blue grain is soft; the white grain is hard. We manually removed the pericarp, germ and pedicel from the maize to obtain the endosperm; we ground part of it and weighed the resulting paste in portions of 2 g, froze them with liquid nitrogen and stored at 20 °C for the electrophoretic analysis of proteins. The remaining endosperm dried at 40 °C for 24 h in a convection oven (Riossa, model HS, Mexico). The powder obtained was used to isolate starch and carry out its characterization. Starch content and isolation in the endosperm We assessed the starch content by using Goñi et al. technique (1997). We isolated the endosperm starch following the methodology proposed by Utrilla-Coello et al. (2009). Apparent amylose and size distribution of the starch granules We quantified apparent amylose with the method by Hoover and Ratnayake (2002), and determined the size distribution of starch granules by laser diffraction analysis (Malvern Instruments, model 2000, USA). Thermal properties Gelatinization properties were determined in 2.2 mg of sample in an aluminum pan and 7 L of deionized water. We heated the samples in the differential scanning calorimeter (TA Instruments, model DSC 2010, USA) from 0 to 130 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min, and used an empty pan as reference. We analyzed samples in triplicate. To measure the properties of retrogradation, we stored gelatinized samples at 4 °C for 7 d, and applied the AGAMA-ACEVEDO et al. 3 AGROCIENCIA, 1 de enero - 15 de febrero, 2013 Propiedades térmicas same heating program used for gelatinization (Bello-Pérez et al., 2005). Las propiedades de gelatinización se evaluaron con 2.2 mg de muestra en una charola de aluminio y 7 L de agua desionizada. Las muestras se calentaron en el calorímetro de barrido diferencial (TA Instruments, modelo DSC 2010, USA) desde 0 a 130 °C a una velocidad de 10 °C/min, y se usó un recipiente vacío como referencia. Las muestras fueron analizadas por triplicado. Para medir las propiedades de retrogradación, las muestras gelatinizadas se almacenaron 7 d a 4 °C. Se aplicó el mismo programa de calentamiento utilizado para gelatinización (Bello-Pérez et al., 2005). For the chain-length distribution of the amylopectin we used high-performance anion-exchange chromatography coupled to a pulse amperometric detector (HPAEC-PAD) (Dionex Co., model DX500, USA) and the method of Chávez-Murillo et al. (2012). We debranched amylopectin with isoamilsa (59 000 U mL1, HBL, Japan) and the products were automatically injected to the equipment. Distribución de las cadenas de la amilopectina Extraction and purification of proteins Para obtener la distribución de la longitud de cadenas de la amilopectina se usó la cromatografía líquida de alta resolución de intercambio anicónico acoplada a un detector de pulsos anemométricos (CLARIA-DPA) (Dionex Co., modelo DX500, USA) y el método de Chávez-Murillo et al. (2012). La amilopectina fue desramificada con isoamilsa (59 000 U mL1, HBL, Japón) y los productos fueron inyectados automáticamente al equipo. We conducted the protein extraction using the method proposed by Borén et al. (2004). We weighed 1 g of endosperm and homogenized it with 10 mL of extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 1 mM EDTA; 1 mM DTT) and then with washing buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8; 10 mM DTT; 2 % SDS). After centrifugation (Hermle Z 383 K centrifuge, Germany), we added 30 mL of wash buffer to the residue and boiled for 15 min under constant stirring. We froze it (20 °C) for 1 h, then thawed (FRIGIDAIRE Freezer, model GLFC1325FW, USA) and centrifuged at 13 000g/30 min at 4 °C, and recovered the supernatant. To the supernatant we added an equal volume of a cold solution (4 °C) of trichloroacetic acid: acetone (30:70 v/v) to precipitate proteins. Extracción y purificación de proteínas La extracción de proteínas se realizó con el método de Borén et al. (2004). Se pesó 1 g de endospermo y se homogenizó con 10 mL de regulador de extracción (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 1 mM EDTA; 1 mM de DTT) y después con regulador de lavado (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8; 10 mM DTT; SDS al 2 %). Tras una centrifugación (Centrifuga Hermle Z 383 K, Alemania), al residuo se adicionaron 30 mL de regulador de lavado y se llevó a ebullición por 15 min con agitación constante. Se congeló (20 °C) por 1 h, y después se descongeló (Congelador FRIGIDAIRE, modelo GLFC1325FW, USA) y centrifugó a 13 000g/30 min a 4 °C y se recuperó el sobrenadante, al cual se adicionó un volumen igual de una solución fría (4 °C) de ácido tricloroacético: acetona (30:70 v/v), para precipitar las proteínas. Electroforesis unidimensional en geles de poliacrilamida (SDS-PAGE) Distribution of the amylopectin chains One-dimensional electrophoresis in polyacrylamide gels (SDS-PAGE) Before quantifying proteins by 2 QUANT KIT (Amersham Biosciences), we prepared polyacrylamide gels at 8 %, which were loaded with 10 g of protein per sample. The electrophoresis was run at 20 mA per gel in a MiniPROTEAN Tetra system equipment (Copyright 2009 Bio-Rad Laboratories). We revealed proteins with colloidal Coomassie blue. Statistical analysis Previa cuantificación de proteínas mediante el 2 QUANT KIT (Amersham Biosciences), se prepararon geles de poliacrilamida al 8 %, en los cuales se cargaron 10 g de proteína por muestra. La electroforesis se corrió a 20 mA por gel en un equipo Mini-PROTEAN Tetra system (Copyright 2009 Bio-Rad Laboratories). Las proteínas se revelaron con azul de coomassie coloidal. 4 VOLUMEN 47, NÚMERO 1 To determine the statistical differences in the physical characterization, starch content, amylose, thermal properties, and distribution of amylopectin chains of the two maize varieties, we applied a one way analysis of variance (p0.05). We used the Tukey test (p0.05) for mean comparison when statistically significant differences were found. CARACTERÍSTICAS DEL ALMIDÓN DE MAÍZ Y RELACIÓN CON LAS ENZIMAS DE SU BIOSÍNTESIS Análisis estadístico Results and Discussion Para determinar las diferencias estadísticas en la caracterización física, contenido de almidón, amilosa, las propiedades térmicas y distribución de las cadenas de la amilopectina de las dos variedades de maices, se aplicó un análisis de varianza de una vía (p0.05). Para diferencias estadísticas significativas, las medias se compararon con la prueba de Tukey (p0.05). Total starch Resultados y Discusión Almidón total El contenido de almidón en el endospermo no presentó diferencias significativas 20 ddp entre el maíz blanco y el maíz azul (71g/100 g) (Cuadro 1), pero cuando ambos maíces llegaron a una madurez fisiológica (50 ddp), la acumulación del almidón en el endospermo fue mayor en el maíz azul (81.7 g 100 g1) que en el blanco (76.22 g 100 g1). El contenido de almidón en el maíz tiene influencia en las propiedades funcionales y nutricionales de los productos elaborados con este cereal, como las tortillas. El almidón es el producto final de la fijación de carbono durante la fotosíntesis, su contenido en el endospermo de maíz incrementa proporcionalmente con el llenado del grano, esta comienza 8 ddp y continua hasta los 45 ddp, con su madurez fisiológica (Prioul et al., 2008). Li et al. (2007) analizaron el contenido de almidón en el endospermo de maíz blanco en diferentes ddp y encontraron que a partir de los 12 ddp (2 g 100 g1) el contenido de almidón incrementó considerablemente hasta permanecer constante después de 30 ddp (88 g 100 g1). Una tendencia destacable encontrada en maíz es que a menor contenido de almidón en el endospermo hay mayor contenido de proteínas, y esto a su vez se asocia al tipo de endospermo, los vítreos contienen más proteína que el harinoso, y el endospermo de tipo harinoso presenta más almidón que el vítreo (SernaSaldivar, 2010). Pero, se desconoce si hay algún tipo de asociación entre estas dos moléculas, si el cese de la biosíntesis del almidón es por restricción de espacio y si esto afecta su estructura. Amilosa aparente El contenido de amilosa aparente 20 ddp presentó diferencias significativas entre el almidón de Starch content in the endosperm showed no significant difference 20 DAP between white and blue maize (71g/100 g) (Table 1), but when both varieties of maize reached physiological maturity (50 DAP), the accumulation of starch in the endosperm was higher in blue maize (81.7 g 100 g1) than in white maize (76.22 g 100 g1). The content of starch in maize has an influence on the functional and nutritional properties of the products made with this cereal, such as tortillas. Starch is the end product of carbon fixation during photosynthesis; its content in maize endosperm increases proportionally with grain filling; it starts 8 DAP and continues until 45 DAP, with the grain physiological maturity (Prioul et al., 2008). Li et al. (2007) analyzed starch content in white maize endosperm at different DAP, and found that from 12 DAP (2 g 100 g1) starch content increased substantially to remain constant 30 DAP (88 g 100 g1). The lower the maize starch in the endosperm, the greater the protein content; this in turn is related to the type of endosperm, being the vitreous characterized for containing the greatest amount of protein compared to the floury; so the floury endosperm has more starch than the vitreous (Serna-Saldívar, 2010). But, it is unknown whether Cuadro 1. Contenido de almidón y amilosa en el endospermo de maíz blanco y azul. Table 1. Starch and amylose content in white and blue maize endosperm. Muestra ddp Almidón† Amilosa¶ Blanco 20 50 70.990.39c 76.221.40b 20.590.42d 32.860.17a Azul 20 50 71.340.22c 81.730.14a 22.350.41c 27.410.30b Media de tres repeticiones el error estándar, muestra en base seca. Valores con diferente letra en una columna son estadísticamente diferentes (p0.05). ddp: días después de la polinización. † g de almidón en 100 g endospermo. ¶g amilosa en 100 g de almidón Mean of three replicates standard error, sample on dry basis. Values with different letter in a column are statistically different (p0.05). dap: days after pollination. †g starch in 100 g of endosperm. ¶g amylose in 100 g of starch. AGAMA-ACEVEDO et al. 5 AGROCIENCIA, 1 de enero - 15 de febrero, 2013 maíz blanco y azul (20.6 y 22.4 g 100 g1) de almidón) (Cuadro 1), pero la diferencia fue más marcada a los 50 ddp entre el maíz blanco (32.9 g 100 g1 de almidón) y el azul (27.4 g 100 g1 de almidón). Además, en el almidón del maíz blanco el incremento de amilosa aparente de los 20 a los 50 ddp fue mayor que en azul. Esto muestra que existen diferencias en el proceso de biosíntesis de esta molécula en los dos tipos de maíces. Considerando que el maíz blanco es un grano duro y el azul uno suave, los resultados concuerdan con lo reportado por Dombrink-Kurtzman y Knutson (1997), quienes sugieren que en un grano duro el contenido alto de amilosa ocasiona que los gránulos de almidón puedan ser comprimidos fácilmente por su matriz proteica, a diferencia de los granos suaves que tiene mas amilopectina. Li et al. (2007) observaron que el contenido de amilosa aumenta paulatinamente con los ddp encontrándose a los 12 ddp 9.2 g 100 g1 de almidón, a los 20 ddp 21.4 g 100 g1 de almidón y a los 30 ddp 24 g 100 g1 de almidón, el cual permanece sin cambio cuando el maíz llega a su madurez fisiológica a los 45 ddp. Es importante señalar que el contenido de amilosa también depende de la variedad, ya que en maíz el intervalo en el contenido de amilosa es 25-35 g 100 g1 de almidón, para almidones normales. La variación de los resultados en este estudio indican que la acumulación de la amilosa dentro del gránulo del almidón difiere entre los almidones, esto podría deberse a factores genéticos de cada grano o a la actividad de la enzima GBSS, responsable de la biosíntesis de amilosa, así como a la disponibilidad de espacio libre dentro de la estructura granular después de sintetizarse la amilopectina, lo cual también involucraría la actividad de las enzimas SSS y SBE. Distribución de tamaño de partícula La distribución del tamaño de gránulo mostró una distribución unimodal en las etapas de desarrollo analizadas (Figura 1). El tamaño de partícula de los gránulos de almidón 20 ddp fue 11.9 m y 13.4 m en el maíz blanco y azul, aumentando ligeramente a los 50 ddp (13.4 m maíz blanco y 14.9 m maíz azul). Los gránulos de almidón de maíz cubren un intervalo amplio en cuanto al tamaño de partícula (2-30 m) y está en función de la terminación de la síntesis del almidón en la etapa 6 VOLUMEN 47, NÚMERO 1 there is any association between these two molecules and whether cessation of starch biosynthesis is due to space restriction, and how this affects its structure. Apparent amylose The apparent amylose content 20 DAP showed significant differences between the white maize starch and the blue maize starch (20.6 and 22.4 g 100 g1 of starch) (Table 1), but the difference was more evident 50 DAP between the white (32.9 g 100 g1 of starch) and blue maize (27.4 g 100 g1 of starch). Furthermore, in the white maize starch the increase of apparent amylose from 20 to 50 DAP was higher than in the blue one. This shows that there are differences in the process of biosynthesis of the molecule in the two types of maize. Considering that white maize is a hard grain and blue a soft one, the results obtained match with those reported by Dombrink-Kurtzman and Knutson (1997), who suggest that in a hard grain the high amylose content causes that starch granules can be easily compressed by the protein matrix, unlike soft grains having more amylopectin. Li et al. (2007) found that the amylose content increases gradually with DAP reaching 9.2 g 100 g1 of starch at 12 DAP; at 20 dap, 21.4 g 100 g1 of starch; and at 30 DAP, 24 g 100 g1 of starch, which remains unchanged when maize reaches physiological maturity at 45 DAP. Importantly amylose content also depends on the variety, as in maize the range of amylose content is between 25-35 g 100 g1 of starch for normal starches. The variation of the results obtained in this study indicate that the accumulation of amylose in the starch granule differs between starches; this could be due to genetic factors of each grain or the activity of the GBSS, enzyme responsible for the biosynthesis of amylose, as well as the availability of space within the grain structure after amylopectin synthesizes, which would also involve the activity of SSS and SBE enzymes. Particle size distribution The granule size distribution was unimodal in the developmental stages examined (Figure 1). The particle size of the starch granules at 20 DAP was 11.9 m and 13.4 m in white and blue maize detecting a slight increase at 50 DAP (13.4 m in CARACTERÍSTICAS DEL ALMIDÓN DE MAÍZ Y RELACIÓN CON LAS ENZIMAS DE SU BIOSÍNTESIS de crecimiento en la que se encuentre el grano de maíz, por lo que se ha sugerido que el desarrollo individual de los gránulos de almidón es paralelo al desarrollo del grano de maíz, considerando que gránulos pequeños (10 m) son gránulos inmaduros que no han alcanzado su tamaño final (Dhital et al., 2011). En el caso del almidón de maíz blanco se observó que 20 ddp el área bajo la curva con valores menores de 10 m fue mayor a la observada 50 ddp; es decir, hubo una población de gránulos pequeños considerable que aumentaron su tamaño pero no el número. En el caso del almidón de maíz azul la población de gránulos pequeños incrementó el número y el tamaño, por lo que el mecanismo de biosíntesis del almidón de maíz azul continuó activamente después de los 20 ddp a diferencia del almidón de maíz blanco. Distribución de las cadenas de la amilopectina El promedio de la longitud de cadena de la amilopectina fue similar a los 20 y 50 ddp, así como en las dos variedades de maíz (blanco GP20 y azul GP19) (Cuadro 2). En ambos almidones de maíz, predominan cadenas pequeñas (GP24), que caracterizan el arreglo cristalino del tipo A de los almidones de cereales. Independientemente de los ddp, el maíz azul presentó mayor porcentaje de cadenas con GP 6-12 y 13-24, pero menor porcentaje de cadenas con GP25 respecto al maíz blanco. Dhital et al. (2011) separaron los gránulos de almidón de maíz en función de su tamaño (9, 13, 26 white maize and 14.9 m in blue maize. Maize starch granules cover a wide range in terms of particle size (2-30 m m) depending on the completion of starch synthesis in the growth stage at which the maize grain is; therefore, the individual development of starch granules has been suggested to be parallel to the development of the maize kernel, considering that small granules (10 m) are immature and have not reached full size (Dhital et al., 2011). In the case of white maize starch, at 20 DAP, we found that the area under the curve showing values below 10 m was greater than that observed at 50 DAP, that is, there is a substantial population of small granules that increased in size but not in number. In the case of blue maize starch, the population of small granules increased in number and size, so the mechanism of biosynthesis of blue maize starch continued active at 20 DAP, unlike the white maize starch. Distribution of the amylopectin chains The average chain length of amylopectin was similar at 20 and 50 DAP, as well as in the two varieties of maize (white DP20 and blue DP19) (Table 2). In both maize starches small chains (DP24) prevail, characterizing the A-type crystalline arrangement of cereal starches. Regardless of DAP, blue maize had a higher number of chains with DP 6-12 and 13-24, but lower percentage of chains with DP25 relative to white maize. Dhital et al. (2011) separated the maize starch granules according to their size (9, 13, 26 20 m), Figura 1. Distribución de tamaño de partícula del almidón de maíz blanco y azul a los 20 y 50 DAP. Figure 1. Particle size distribution of white and blue maize starch at 20 and 50 DAP. AGAMA-ACEVEDO et al. 7 AGROCIENCIA, 1 de enero - 15 de febrero, 2013 Cuadro 2. Distribución de las cadenas de amilopectina en almidón de maíz blanco y azul. Table 2. Distribution of amylopectin chains in white and blue maize starch. Distribución de cadena (%) Muestra ddp LC (GP) (GP 6-12) (GP 13-24) (GP 25-36) (GP ≥ 37) Blanco 20 50 20.450.2a 20.490.1a 23.080.2b 23.470.3b 51.840.4b 50.620.3c 15.170.2b 16.170.1a 9.900.2a 9.740.3a Azul 20 50 19.450.1b 19.520.1b 25.700.2a 25.790.2a 52.150.2a 51.620.3b 13.960.2d 14.630.3c 8.190.2b 7.960.1b Media de dos repeticiones el error estándar. Valores con diferente letra en una columna son estadísticamente diferentes (p0.05). LC: longitud de cadena promedio; GP: grado de polimerización. ddp: días después de la polinización Mean of two replicates standard error. Values with different letter in a column are statistically different (p0.05). LC: mean chain length, DP: degree of polymerization. DAP: days after pollination. 20 m), encontrando que la mayoría de las distribuciones de la longitudes de cadenas fueron idénticas en los diferentes tamaños de gránulos. Pero en maíz cosechado a 20 y 45 ddp (con tamaños de gránulos aproximados de 10-16 y 23 m) las cadenas con GP12 aumentaron de 16 a 19 %, las de GP 1324 no cambiaron, las de GP 25-36 disminuyeron de 15 a 13 % y las de GP37 disminuyeron de 21.1 a 20.8 % (Jane, 2007). Este tipo de estudios en almidones ha derivado ciertos patrones en cuanto estructura-propiedades fisicoquímicas; pero hay reportes en almidones con características estructurales similares y que presentan diferencias en sus características fisicoquímicas y viceversa (De la Rosa-Millan et al., 2010; PalmaRodríguez et al., 2012). Lo anterior, hace suponer que las longitudes de cadenas de la amilopectina son responsables de estas propiedades y también la organización y distribución de ellas dentro de los anillos concéntricos, que conforman la estructura granular, y las interacciones que pudieran tener con la amilosa. Propiedades de gelatinización y retrogradación La gelatinización es un fenómeno que involucra la disociación de las dobles hélices de la estructura cristalina de la amilopectina en presencia de agua (arriba del 70 % en base al peso seco de almidón) por efecto de la temperatura. Mayores temperaturas de pico o promedio (TpG73 °C) y entalpías de gelatinización (HG10.5 J g1 y 8.2 J g1 blanco y azul) a los 20 ddp se encontraron con respecto a las 50 ddp 8 VOLUMEN 47, NÚMERO 1 and found that most of the chain-length distributions were identical in the different granule sizes. But, Jane (2007) in maize harvested at 20 and 45 DAP (with approximate granule sizes of 10-16 and 23 m) the DP12 chains increased from 16 to 19 %, DP 1324 did not change, DP 25-36 decreased from 15 to 13 %, and DP37 decreased in smaller proportion, from 21.1 to 20.8 % (Jane, 2007). This type of study on starches has led to certain structural patterns in relation to structurephysicochemical properties; but there are reports on starches with similar structural features and differing in their physicochemical characteristics and vice versa (De la Rosa-Millán et al., 2010; Palma-Rodriguez et al., 2012). The foregoing suggests that not only the lengths of amylopectin chains are responsible for these properties, but also the organization and distribution of the chains within the concentric rings forming the granular structure and the interactions they may have with amylose. Properties of gelatinization and retrogradation Gelatinization is a phenomenon involving the dissociation of double helices of amylopectin crystalline structure in the presence of water (up to 70 % based on the dry weight of starch) by the effect of temperature. We found higher peak or mean temperatures (TpG73 °C) and gelatinization enthalpy (HG10.5 J g1 and 8.2 J g1, white and blue) at 20 DAP with respect to the 50 DAP (72 °C and 69 °C and H 9.7 J g1 and 7 J g1, white CARACTERÍSTICAS DEL ALMIDÓN DE MAÍZ Y RELACIÓN CON LAS ENZIMAS DE SU BIOSÍNTESIS (72 °C y 69 °C y H 9.7 J g1 y 7 J g1, blanco y azul) (Cuadro 3). Hubo una mayor disminución de los valores en estos parámetros de los 20 a 50 ddp en el almidón de maíz azul. Los resultados podrían estar influenciados por el aumento en el contenido de amilosa, lo cual causa la disminución de la proporción de amilopectina, ocasionando que se requiera menor temperatura y energía para gelatinizar el almidón; sin embargo, el almidón de maíz blanco fue el que aumentó en mayor medida la proporción de amilosa, y se esperaría que su TpG y HG fueran menores que las del almidón del maíz azul. Pero algunas cadenas de amilosa forman dobles hélices con cadenas de amilopectina individuales o estan entretejidas entre las moléculas de amilopectina, reforzando de esta manera la estructura granular (Tako e Hizukuri, 2002). El almidón de maíz blanco no presentó diferencias en su temperatura de retrogradación (TpR) de los 20 a los 50 ddp, pero si un aumento en la entalpia (HR), lo contrario ocurrió en el almidón de maíz azul. El proceso de retrogradación del almidón de maíz blanco forma cristales con mayor perfección y en menor cantidad que el almidón de maíz azul. El porcentaje de retrogradación (%R) indica la cantidad de re-arreglo estructural del almidón en un tiempo determinado. Los %R fueron mayores a los 50 ddp independientemente del tipo de maíz, pero el almidón de maíz azul presentó altos %R a los diferentes ddp analizados. Hyun-Jung y Quian (2009) y Shifeng et al. (2009) mencionan que la amilosa es la principal responsable de la retrogradación, debido a que sus and blue) (Table 3). There was a greater decrease in these parameters of 20-50 DAP in blue maize starch. The results may be influenced by the increase in amylose content, which causes the decrease of the proportion of amylopectin, thus requiring lower temperature and energy to gelatinize the starch; but it was white maize starch the one that further increased the proportion of amylose, and its TpG and HG were expected to be lower than those of blue maize starch. However, some amylose chains form double helices with individual amylopectin chains or are woven between amylopectin molecules, thereby reinforcing the granular structure (Tako and Hizukuri, 2002). The white maize starch did not differ in its retrogradation temperature (TpR) at 20 to 50 DAP, but did increase in enthalpy (HR); we observed the opposite in blue maize starch. The process of retrogradation of white maize starch forms more perfect crystals and in lesser amount than in the blue maize starch. The percent of retrogradation (%R) indicates the amount of structural rearrangement of the starch at a given time. The %R was greater at 50 DAP regardless of the type of maize, but blue maize starch showed high %R at the different DAP analyzed. Hyun-Jung and Qian (2009) and Shifeng et al. (2009) mention that amylose is primarily responsible for retrogradation because its linear chains are bonded through hydrogen bridges forming a network that begins to grow or thicken as storage time passes; so the greater the amylose content, the higher retrogradation. But Hyun-Jung and Quiag (2009), Cuadro 3. Temperatura y entalpía de gelatinización y retrogradación de almidón de maíz blanco y azul. Table 3. Temperature and enthalpy of gelatinization and retrogradation of white and blue maize starch. Muestra ddp Tp (°C) H (J/g) TpR(°C) HR(J/g) %R Blanco 20 50 73.680.10 a 72.400.03b 10.520.26a 9.690.12a 51.350.13b 51.640.52b 5.080.20a 6.480.46a 49 67 Azul 20 50 73.300.32ab 68.850.32c 52.731.13ab 55.050.39a 5.800.45a 5.650.83a 71 79 8.230.18ab 7.080.99b Valores en una columna con diferente letra son significativamente diferentes (p0.05). Promedio de tres repeticiones error estándar. TpG: temperatura promedio de gelatinización; HG: entalpía de gelatinización; TpR: temperatura promedio de retrogradación; HR: entalpía de retrogradación; %R: porcentaje de retrogradación; ddp: días después de la polinización Values in a column with different letter are significantly different (p0.05). Mean of three replicates standard error. TpG: mean gelatinization temperature; HG: enthalpy of gelatinization; TpR: mean retrogradation temperature; HR: enthalpy of retrogradation; %R: percentage of retrogradation; DAP: days after pollination. AGAMA-ACEVEDO et al. 9 AGROCIENCIA, 1 de enero - 15 de febrero, 2013 cadenas lineales se unen a través de puentes de hidrógeno formando una malla que empieza a crecer o engrosarse conforme transcurre en tiempo de almacenamiento, por lo que a mayor contenido de amilosa mayor retrogradación. Pero Hyun-Jung y Quiag (2009) más que asociar la retrogradación al contenido de amilosa lo asocian con la longitud de sus cadenas. Relación de las enzimas de biosíntesis con las características del almidón El análisis electroforético (Figura 2) muestra bandas con pesos moleculares (PM) reportados para las enzimas que sintetizan almidón en un intervalo de 50 a 188 kDa (Grimaud et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2004; Mu Foster et al., 1996). Ambos maíces mostraron una banda predominante a 55 kDa, que es el PM reportado para GBSSI. Aunque esta enzima es la responsable de la síntesis de amilosa, su actividad depende la formación de la matriz cristalina dada por la estructura de la amilopectina, lo cual pudo ocasionar diferencias en el contenido de amilosa 50 ddp en los dos tipos de maíz (Cuadro 1). Otras bandas fueron: 64 kDa (SSSI), 72 kDa (SSSIIa), 73 kDa (SBE IIb), 76 kDa (SBEI), 100 kDa reportada como glucosa pirofosforilasa y 188 kDa (SSSIII) (Grimaud et al., 2008). Estos resultados indican que en ambos maíces se sintetizan cadenas lineales cortas con GP 6-12, cadenas intermedias con GP 13-24, cadenas con GP mayores a 24 (Gao et al., 1998), siendo éstas PM (kDa) E 250 Blanco 150 Fosforilasa SBEIIa SBEIIb SBEI SBEIIb SBEIIa 75 SSSI GBSSI 50 10 VOLUMEN 47, NÚMERO 1 Relationship of biosynthetic enzymes with starch characteristics The electrophoretic analysis (Figure 2) shows bands with molecular weights (MW) reported for the enzymes that synthesize starch, found in a range of 50 to 188 kDa (Grimaud et al., 2008, Zhang et al., 2004; Mu Foster et al., 1996). Both maize varieties showed a predominant band at 55 kDa, which is the MW reported for GBSSI. Although this enzyme is responsible for amylose synthesis, its activity depends upon the formation of the crystal matrix provided by the amylopectin structure, which could cause differences in the content of amylose 50 DAP in the two types of maize (Table 1). Other bands were: 64 kDa (SSSI), 72 kDa (SSSIIa), 73 kDa (SBE IIb), 76 kDa (SBEI), 100 kDa reported as glucose pyrophosphorylase, and 188 kDa (SSSIII) (Grimaud et al., 2008). These results indicate that in both maize varieties short linear chains are being synthesized with DP 6-12, as well as intermediate chains with DP 13-24, chains with DP greater than 24 (Gao et al., 1998), being these the substrate for SBEI and SBEIIb that link chains with DP higher than 10 and chains with DP 3-9 (Guan and Preiss, 1993). This is consistent with the chain length results of the starches analyzed (Table 2). The bands found in blue maize with 85 MW and 90 kDa correspond to those reported Azul SSSIII 100 rather than associating retrogradation with amylose content, do so with the length of its chains. Figura 2. SDS-PAGE de proteínas extraídas del endospermo de maíz blanco y azul. E: marcador de pesos moleculares; PM: peso molecular. GBSSI: almidón sintasa unida al granulo, isoforma I; SSS: almidón sintasa soluble, isoformas I, IIa y III; SBE: enzima ramificante del almidón, isoformas I, IIa y IIb. Figure 2. SDS-PAGE of proteins extracted from white and blue maize endosperm. E: molecular weight marker; MW: molecular weight. GBSSI: granule bound synthase starch, isoform I; SSS: soluble synthase starch, isoforms I, IIa and III; SBE: starch branching enzyme, isoforms I, IIa and IIb. CARACTERÍSTICAS DEL ALMIDÓN DE MAÍZ Y RELACIÓN CON LAS ENZIMAS DE SU BIOSÍNTESIS sustrato para las SBEI y SBEIIb que unen cadenas con GP mayor a 10 y cadenas con GP 3-9 (Guan y Preiss, 1993). Lo anterior concuerda con los resultados de longitud de cadena de los almidones analizados (Cuadro 2). Las bandas encontradas en maíz azul con PM de 85 y 90 kDa corresponden a los reportados para SBEIIb (Mu Foster et al., 1996) y SBEIIa (Grimaud et al., 2008). La diferencia entre estas dos enzimas es que la primera transfiere cadenas más cortas que la segunda (Mizuno et al., 2001), lo cual puede causar que la amilopectina del almidón de maíz azul presente mayor número de ramificaciones que la del almidón de maíz blanco, reflejándose en la formación de cristales pequeños que fueron desorganizados a menor temperatura (Cuadro 3), y en espacios menos disponibles para la síntesis de la amilosa dentro de la estructura granular. Conclusiones El contenido de almidón y amilosa 20 ddp fue similar en ambos maíces, pero 50 ddp el maíz azul acumuló mayor cantidad de almidón y menor cantidad de la cadena de amilosa. La población de gránulos de almidón menores a 10 m incrementó en número y tamaño en el almidón de maíz azul. Hay dos isoformas de la enzima ramificante en el almidón de maíz azul, produciendo moléculas de amilopectina altamente ramificadas con cadenas cortas dejando menor espacio disponible dentro de la estructura granular para la síntesis de amilosa. El almidón de maíz azul gelatinizó a mayor temperatura y entalpía que el almidón de maíz blanco. La organización y distribución de las cadenas de la amilopectina dentro de los anillos concéntricos que conforman la estructura granular afectan las propiedades fisicoquímicas del almidón. Agradecimientos Se agradece el financiamiento otorgado por la SIP-IPN, COFAA-IPN, EDI-IPN y CÁTEDRA COCA-COLA. Dos de los autores (OLRR y EJG) agradecen la beca otorgada por el CONACYT-México. Literatura Citada Agama-Acevedo, E., A. P. Barba de la Rosa, G. MéndezMontealvo, and L. A. Bello-Pérez. 2008. Physicochemical for SBEIIb (Mu Foster et al., 1996) and SBEIIa (Grimaud et al., 2008). The difference between these two enzymes is that the first one transfers shorter chains than the second (Mizuno et al., 2001), which could cause the blue maize starch amylopectin to show a higher number of branches than that of white maize starch. This reflects in the formation of small crystals that were disrupted at lower temperatures (Table 3), and in less available spaces for the synthesis of amylose within the granular structure. Conclusions The starch and amylose content 20 DAP was similar in both maize varieties, but 50 DAP blue maize accumulated more starch and less amylose content than white maize. The population of starch granules smaller than 10 µm increased in number and size in blue maize starch. There are two isoforms of branching enzyme in the blue maize starch, producing highly branched amylopectin molecules with short chains, leaving less space available within the grain structure for amylose synthesis. We gelatinized the blue maize starch at higher temperature and enthalpy than white maize starch. The organization and distribution of the amylopectin chains within the concentric rings forming the granular structure affect the physicochemical properties of starch. —End of the English version— pppvPPP and biochemical characterization of starch granules isolated of pigmented maize hybrids. Starch/Stärke 60: 433-441. Baldwin, P. M. 2001. Starch granule-associated protein and polypeptides: A review. Starch/Starke 53: 475-503. Bello-Pérez, L. A., M. A. Ottenhof, E. Agama-Acevedo, and I. A. Farhat. 2005. Effect of storage time on the retrogradation of banana starch extrudate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53: 10811086. Borén, M., H. Larsson, A. Falk, and C. Jansson. 2004. The barley starch granule proteome linternalized granule polypeptides of the mature endosperm. Plant Sci. 166: 617-626. Chávez-Murillo, C. E., G. Méndez-Montealvo, Y. J. Wang, and L. A. Bello-Pérez. 2012. Starch af diverse Mexican rice cultivars: physicochemical, structural, and nutritional features. Starch/Starke 64: 745-756. Dhital, S., A. K. Shrestha, J. Hasjim, and M. J. Gidley. 2011. Physicochemical and structural properties of maize and potato starches as a function of granule size. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59: 10151-10161. AGAMA-ACEVEDO et al. 11 AGROCIENCIA, 1 de enero - 15 de febrero, 2013 De la Rosa-Millan, J., E. Agama-Acevedo, A.R. Jiménez-Aparicio, and L.A. Bello-Pérez. 2010. Starch/Starke 62: 549-557. Dombrink-Kurtzman, M. A., and C. A. Knutson. 1997. A study of maize endosperm hardness in relation to amylose content and susceptibility to damage. Cereal Chem. 74: 776-780. Gao, M., H. P. Guan, and P. L. Keeling. 1998. Starch biosynthesis: Understanding the functions and interactions of multiple isozymes of starch synthase and brancing enzyme. Trends Glycosci. Glyc. 10: 307-319. Goñi, I., A. García-Alonso, and F. Saura-Calixto. 1997. A starch hydrolysis procedure to estimate glycemic index. Nutr. Res. 17: 427-437. Grimaud, F., H. Rogniaux, M. G. James, A. M. Myers, and V. Planchot. 2008. Proteome and phosphoproteome analysis of starch granule-associated proteins from normal maize and mutants affected in starch biosynthesis. J. Exp Bot. 59: 3395-3406. Guan H. P., and J. Preiss. 1993. Differentiation of the properties of the branching isozymes from maize (Zea mays). Plant Physiol. 102: 1269-1273. Hernández-Uribe, J. P., E. Agama-Acevedo, J. J. Islas-Hernández, J. Tovar, and L. A. Bello-Pérez. 2007. Chemical composition and in vitro starch digestibility of pigmented corn tortilla. J. Sci. Food Agric. 87: 2482-2487. Hoover, R., and W. S. W. Ratnayake. 2002. Starch characteristics of black bean, chick pea, lentil, navy bean and pinto bean cultivars grown in Canada. Food Chem. 78: 489-498. Hyun-Jung, C., and L. Quiag. 2009. Impact of molecular of amylopectin and amylose chain association during cooling. Carbohydr. Polym. 77: 809-815. Jane, J. L. 2007. Structure of starch granules. The Japanese Soc. Appl. Glycosci. 54: 31-36. Li, L., M. Blanco, and J. Jane. 2007. Physicochemical properties of endosperm and pericarp starches during maize development. Carbohyd. Polym. 67: 630-639. Mizuno, K., E. Kobayashi, M. Tachibana, T. Kawasaki, T. Fugimura, K. Funane, M. Kobayashi, and T. Baba. 2001. Characterization and isoforms of rice starch branching enzyme RBE4 in developing seeds. Plant Cell Physiol. 42: 349-357. 12 VOLUMEN 47, NÚMERO 1 Mu-Foster, C., R. Huang, J. R. Poers, R. W. Harriman, M. Knight, G. W. Singletary, P. L. Keeling, and B. P. Wasserman. 1996. Physical association of starch biosynthetic enzymes with starch granules of maize endosperm. Plant Physiol. 111: 821-829. Palma-Rodríguez, H., E. Agama-Acevedo, G. MendezMontealvo, R.A. Gonzalez-Soto. E. J. Vernon-Carter, and L. A. Bello-Pérez. 2012. Effect of acid treatment on the physicochemical and structural characteristics of starches from different botanical sources. Starch/Starke. 64: 115-125. Prioul, J. L., V. Méchin, P. Lessard, C. Thévenot, M. Grimmer, S. Chateau-Joubert, S. Coates, H. Hartings, M. Kloiber-Maitz, A. Murigneux, X. Sarda, C. Damerval, and K. J. Edwards 2008. A joint transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolic analysis of maize endosperm development and starch filling. Plant Biotechnol. J. 6: 855-869. Serna-Saldivar, S. O. 2010. Grain development, morphology, and structure In: Serna Saldivar, S. O. Cereal Grains. CRC Press (Ed). pp: 109-129. Shifeng, Y., M. Ying, and S. Da-Weng. 2009. Impact of amylose content on starch retrogradation and textute of cooked milled rice during storage. J. Cereal Sci. 50: 139-144. Smith, A. M. 2001. The biosynthesis of starch granules. Biomacromolecules, 2: 335-341. Tako, M., and S. Hizukuri. 2002. Gelatinization mechanics of potato starch. Carbohyd. Polym. 48: 397-401. Tetlow, I. J., M. K. Morell, and M. J. Emes. 2004. Recent developments in understanding the regulation of starch metabolism in higher plants. J. Exp. Bot. 55: 2131-2145. Utrilla-Coello, R. G., E. Agama-Acevedo, A. P. Barba de la Rosa, J. L. Martínez-Salgado, S. L. Rodríguez-Ambríz, and L. A. Bello-Pérez. 2009. Blue maize: morphology and starch synthase characterization of starch granule. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 64: 18-24. Zhang X. L., C. Colleoni, V. Ratushna, M. Sirghle-Colleoni, M. G. James, and A. M. Myers. 2004. Molecular characterization demonstrates that the Zea mays gene sugary2 codes for the starch synthase isoform SSIIa. Plant Mol. Biol. 54: 865-879.